Palladio Awards

Michael Burch Architects Update a Historic Spanish Colonial

2014 PALLADIO AWARDS

Adaptive Reuse &/or Sympathetic Addition

Winner: Michael Burch Architects

Project:Alta Canyada Residence, La Cañada Flintridge, CA

Architect: Michael Burch Architects, La Cañada Flintridge, CA; Michael Burch, AIA, Diane Wilk, AIA, principals

By Nancy A. Ruhling

During the last three decades, architect Michael Burch, AIA, has made a name for himself by devoting his practice exclusively to the Spanish Colonial and Mediterranean Revival styles that were the shining stars of the California landscape of the 1920s and 1930s. He and his wife, Diane Wilk, AIA, have been internationally recognized for their restorations and renovations of high-end residential projects by the likes of George Washington Smith, Wallace Neff, Paul Williams and Arthur Kelly, as well as for new construction in these iconic styles.

When it came to their own home, the California duo, who are based in La Cañada Flintridge, Indian Wells and Lake Arrowhead, chose a special one: Not only was it designed by Kelly, but it was also was the one he built for himself. Kelly, as they well knew, had designed and built more than 500 Tudor Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival houses in the Los Angeles area. His most famous projects are the Arthur Letts Jr. estate in Holmby Hills, now known as the Playboy Mansion, the Westlake School for Girls, which became the Harvard-Westlake School in Bel-Air, and the Wilshire Country Club in Hancock Park.

What they did not know was that they had a personal connection to Kelly. “Kelly’s grandson contacted us and asked to see our home,” says Burch. “He had been going through files and realized that Kelly had also designed the house my grandfather built for himself. My grandfather was a builder who I knew had constructed Kelly’s Westlake School, but I had no idea that Kelly had designed the beautiful Spanish Colonial Revival house next to the Wilshire Country Club that my father had been so proud to grow up in. The house was sold before my time, so I never got to go in it, but my father used to point it out to me when we drove by.”

Burch and Wilk originally had simple plans for Kelly’s own 1925 house, set in the mountain foothills of Los Angeles overlooking downtown to the sea. Their plans, however, soon changed radically when Wilk found out she was having triplets, so they went back to the drawing board and came up with a design that doubled the size of the three-bedroom, two-bath, 2,300-sq.ft. house without compromising Kelly’s original ideas. “We restored the house to its original condition where possible, renovated it as needed and added on in a seamless manner, maintaining or enhancing the details of its Spanish Colonial Revival style,” says Burch. “It became a three-phase, 13-year project.”

Burch and Wilk added an office with a private entry and bathroom; a powder room; a second master bedroom, bath and dressing area; a library; a study and family room that each have fireplaces; a pool, spa and fountains; and a third garage bay. They upgraded the master bedroom, reworked the entry, upgraded and enlarged the kitchen and remodeled the bathrooms.

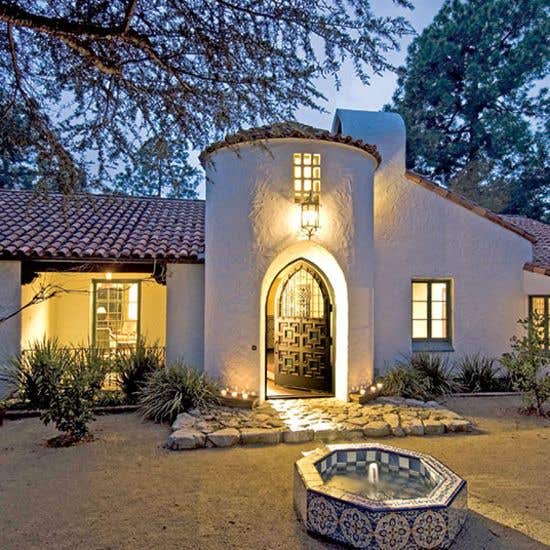

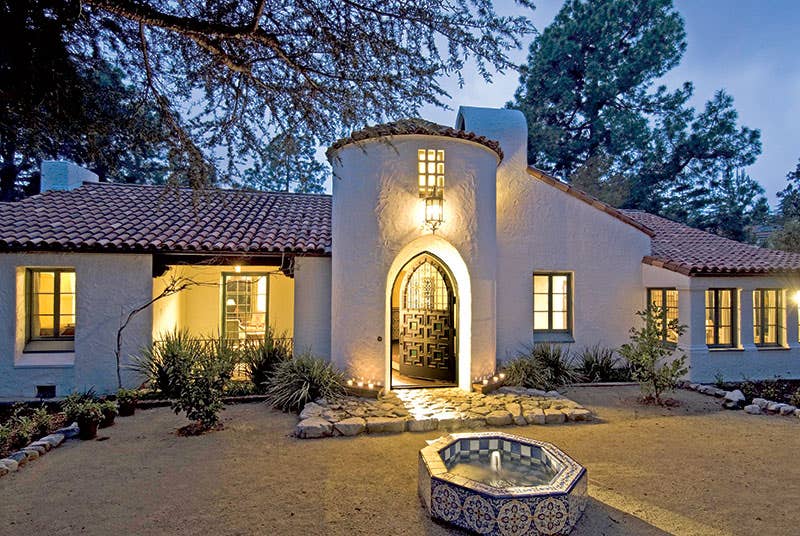

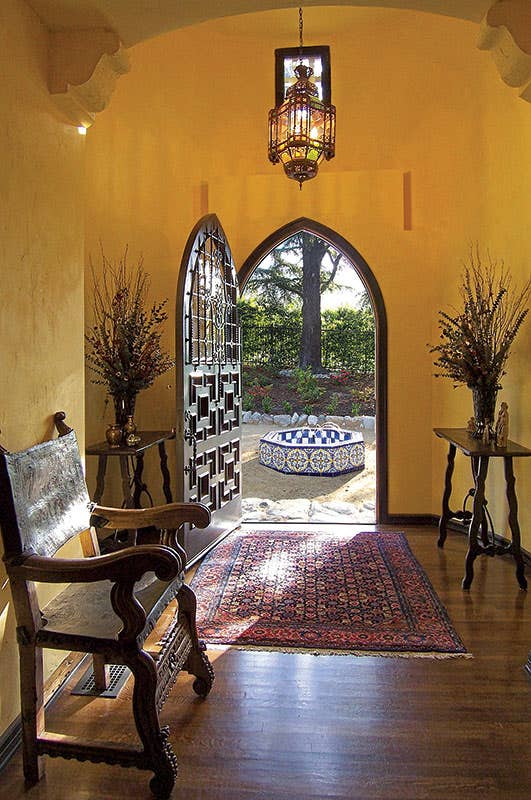

As far as landscaping, they developed the back-yard slope, creating meandering stone-lined pathways that lead to a meadow on the half-acre property – sited so that it is virtually hidden from neighboring houses. The front yard was designed as a Mudéjar garden complete with fountain. The heavily overgrown canopy of trees was trimmed back so that the framed view down the canyon of downtown Los Angeles and Catalina Island in the distance was again visible, as it must have been back when the house was built.

Despite the addition of two floors on the back, from the street, the one-story house looks largely unchanged and the same size as when Kelly moved in just before Hollywood’s Golden Age. The front façade of the stucco house is still anchored by a central tower. But this centerpiece is now flanked by a new chimney, library addition and the powder room, whose construction required the removal of a small section of an iron-railed porch.

“We built above and below the original house without disturbing Kelly’s footprint,” says Burch. “We were restricted by side-yard setbacks and rear-building pad limitations. We minimized the overall square footage of the project by constructing rooms en-suite. By doing all of these things, we were able to incorporate three full floors in a 27-ft. height limit.”

The family room, carved out from under the existing house to expand a cramped subterranean 8-ft. by 12-ft. laundry room, is a prime example of their creative floor plan. In addition, natural light was important; more than half the rooms in the house have windows on three sides.

In most of the projects Wilk and Burch design, the old and the new fit together so well that it is nearly impossible to tell where one begins and the other ends. In this case, however, they deliberately delineated the 20th-century and 21st-century spaces. “This is a locally registered landmark house,” says Burch. “To be eligible for property tax abatements given to historic properties, we had to follow the guidelines of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Modern, which was founded in 1928 and is biased toward the Modernist movement. I have a lot of arguments with this, but it required us to clearly differentiate the alternations.”

One way they did this was to make the additions a foot lower, a decision that allowed for higher ceilings. They also used tile as a floor covering to contrast with the home’s original oak floors. In addition, there were modern engineering considerations that could very well have undermined the Classical integrity of the new spaces. The house is only 200 ft. from a major earthquake fault, so it required the addition of three steel moment frames. What’s more, it is in the state’s highest-rated urban fire zone, which called for fire-resistant construction on the exterior.

Nevertheless, they skillfully tied together the two centuries through the use of historically accurate detailing. The lower-level family room, for instance, features a groin-vaulted ceiling. “This house did not have any, but it was common to the style,” says Burch.

Several of the new rooms, notably the master bedroom and children’s bedroom, have beamed and paneled ceilings that pay homage to the Spanish Colonial Revival. Panels on new doors feature stencils that match the originals. “This was an inexpensive and easy treatment,” says Wilk. “It is a great detail that adds richness.”

New cabinets in the library and office have recessed painted panels that are similar to those in the original dining room, which, like the living room, Burch and Wilk left untouched. In some cases, they let history speak in a subtle manner, referencing the past in such a way as to please connoisseurs and laymen alike. “The master bedroom, whose ceiling panels are trimmed in ochre, green, red and blue, was inspired by George Washington Smith’s legendary Casa del Herrero in Montecito, CA,” says Burch.

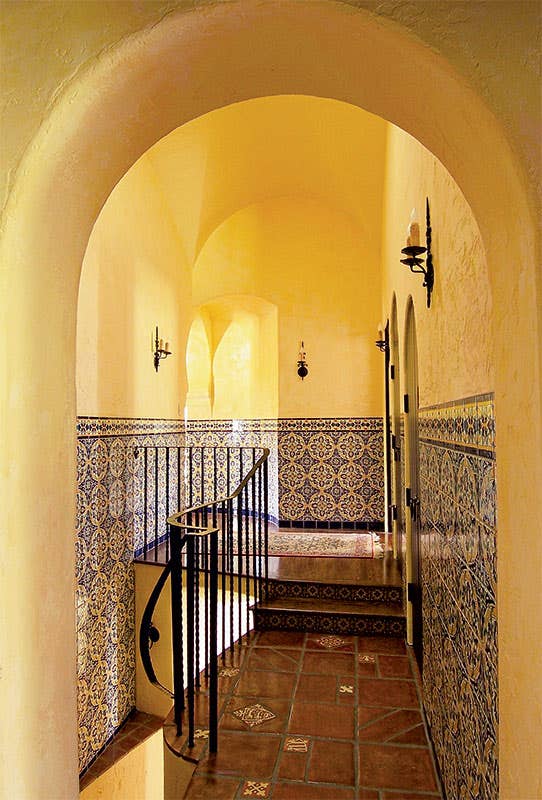

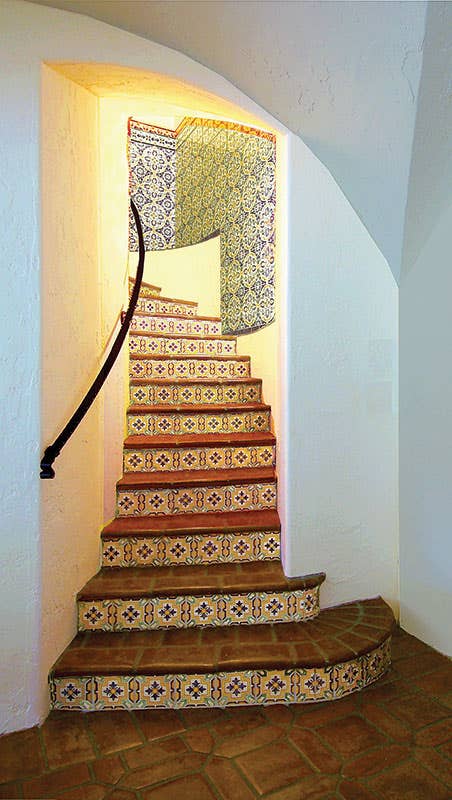

The added ornamentation that has the biggest impact is the decorative Tunisian tile, which Burch and Wilk sourced from the same factory Kelly and his contemporaries used; it looks as though it has always been there. “We got a call from a noted collector who had seen a photo of one of the stairways, where we used it on the risers, and it looked so authentic that he thought it was antique,” says Wilk.

In addition to the stairways, Burch and Wilk decorated the lower portion of the hallway walls with tile, creating a warm and colorful mural-like effect that reflects the golden sun. “We were able to do this because we opened up the hall by doubling its width when we removed a closet,” says Burch.

The architects are particularly proud of the tile work that defines the sink in the top-floor powder room. Because the space was small, they created a long, narrow and shallow niche for the round sink, covering it with period-style highly patterned Tunisian and cobalt tiles that call attention to the home’s Spanish Colonial heritage.

To further the historic theme, Burch and Wilk furnished the house with a variety of Spanish Colonial antiques that range from the 16th-century Spanish headboard in the master bedroom to Spanish Colonial Revival sofas from the 1920s.

Burch and Wilk found that renovating their own house was particularly rewarding. “The client was great,” jokes Burch. “I’d be happy to work with him again.”