Windows & Doors

Designing A Classical Doorway

Few would dispute that a classical doorway is essential to any period-style home but--columns and pediments aside--is there anything that makes an entrance specifically classical? Perhaps it depends upon your point of view.

At Historic Doors in Kempton, Pennsylvania, Steve Hendricks says his company’s goal is to design entrances that look like they’ve always been there. “The doorway really should be a microcosm of the whole, entire building ensemble,” he says. “It is the frontispiece, so to speak, of the building’s composition.” Christine Pape at Borano in East Lodi, New Jersey, says for her customers, “The two big categories of doors are either the classical or modern.” But whether she’s working with an architect, designer, or homeowner, “Even within each of these categories there are different types of designs.” Offers Mary Ayala at Designer Doors in River Falls, Wisconsin, “The biggest thing that we try to do is match the architectural style of the house.” She says they try to educate their customers as well as offer full design services. Nonetheless, “There are some designs that look good on one house, but not as good on another.”

Over and above the actual details, prominence has long been a primary characteristic of a classical entrance. In 1899, Oliver Coleman observed in Successful Houses that, “There may be many windows, but only one main doorway, and it should dominate, in a measure, the entire façade.” Position is one way to achieve that dominance. “Centering the entrance is an important classical concept,” explains Steve Hendricks of Historic Doors. “Rather than having to go around something, or go in on the side of something, you [enter the building] on a center axis.” This makes sense for an architecture based on order, balance, rationality, and symmetry. Sheer size of course can help entrances stand out. “We’ve done entrance units as big as 12 feet tall,” says Ayala.

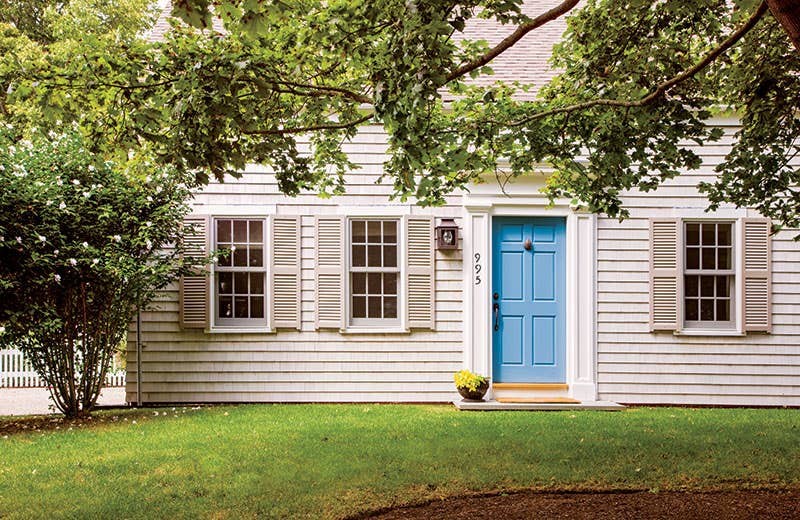

Hendricks adds, “You can take a very plain, simple building and transform it into something that is really appealing, sits on the ground, and relates to the public in a very genteel manner simply by focusing on the entryway.” Indeed, this is just what we see in the classically derived houses of late 18th and early 19th centuries. Whether you call them Georgian, Federal, Adam, or Neoclassical, entrances are the focus of the façade—even sole emblems of the style in cases where other details, such as at windows or cornices, are minimal.

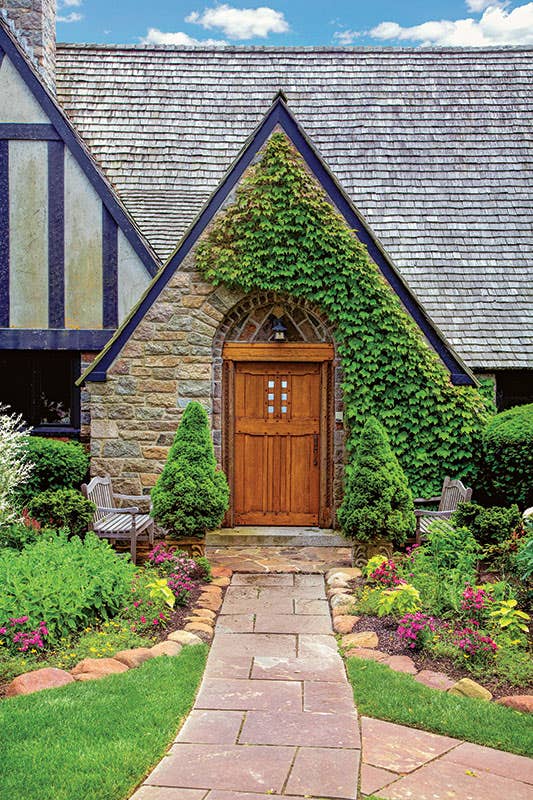

Contrast this with the medieval influence found in the Gothic Revival, Romanesque, and Queen Anne houses of the mid- and latter 19th century that often put a cathedral- or fortress-like spin on entrances with off-center placement or a cavernous inset or hood. Or better yet the modern movement of the 20th century that, at times, had entrances so undifferentiated from windows and walls they disappeared.

“The doorway really should be a microcosm of the whole, entire building ensemble. It is the frontispiece, so to speak, of the building’s composition.”

Sidelights

A monumental door alone can connote prominence, but sidelights (which appear in many architectural styles) often go hand-in-glove with a classical entrance. “An entryway is often double-door width, in terms of its proportioning and the opening into the house,” says Hendricks “We always encourage clients to consider a single door with sidelights.” He notes the mechanical advantages of letting light into the entry hall as well as providing a smaller, more secure way of seeing who’s at the door. “Sidelights also give the opening more grace, more welcoming from the curb than a single, solid door might offer.”

Like traditional windows, sidelights are close cousins to traditional doors in both construction and design, but that does not mean they can’t run on their own aesthetic track. Pape, whose company specializes exclusively in mahogany products, notes that the amount of wood that is apparent can influence the stylistic perception. “More wood means that the sidelights appear thicker—with thicker frames and thicker muntins—and that usually gives them a more classical, less modern look compared to thinner wood and more glass.” She also adds that curved mouldings and muntins read as classical compared to the straight, flat stock associated with modern design.

Says Hendricks, “In our work, we do a lot of fanlights and radiused tracery patterns in sidelights, including bulls-eye glass, ovals, and diamonds, most of which pertain to Federal and Classical Revival styles.” The Greek Revival, he says, sometimes used decorative glass – often expressed in leaded glass instead of wood bars—but tended to have not as much curved work. “In terms of the entrance functioning as a sort of frontispiece, it becomes more and more jewel-like as you adorn it with that kind of work.”

Sidelight muntin grid patterns may be synchronized, so to speak, with those in the door, or they may be contrasting. “For example, if there is row of four lights in the door itself,” says Ayala, “generally the sidelight will be about the same: four lights down, with maybe an additional two lights. But those four lights will often match up with whatever the breakdown is on the door, so it makes an even plane going across the entrance.” In other instances, however, sidelights and door are not related. “That’s usually the case when you have full glass panels in the sidelights, because matching full glass would be much harder to do in a door.” She adds, “It really depends upon how attached to symmetry the people involved are.”

Doors

With doors themselves, the touchstones for a classical entrance become a little clearer, turning again on the difference between medieval and ancient Greco-Roman influences—or, to put it into images, the heavy plank-and-batten door versus the more sophisticated frame-and-panel door. A century ago, when both types were in vogue, Oliver Codman noted that in contrast to the “ancient idea of defense,” which produced entrance doors “narrow and low, of heavy oak, studded with nails, and protected with iron bars,” doors should emphasize hospitality and so be “broad and open, with wide landing and a smiling countenance.” Nonetheless, he added, “In houses of the Richardson type, where the whole effect is massive and fortress-like, it is necessary for consistency’s sake to retain the embattled doorway, but modified as far as may be to prevent a forbidding aspect.”

In this light, frame-and-panel doors say classical, but are any panel patterns more classical or more popular than others? Not to judge by history or today’s work. “We don’t really see any fashions,” says Hendricks. “We have a great wealth of tradition in terms of door styles, and that’s an endless resource in terms of beautiful things that have always been done, and elements that can be taken and brought forward.” Pape agrees. “There’s no specific trend on the number of panels, because you can have a one-panel door that’s as classic as a three- , four-, or five-panel door. It’s really according to the taste of the customer.”

She adds though that in a classical door, there are more raised panels than, say, a modern-style door that is typically flatter. “The casing that you put around the doorway also comes into play,” she says, “with classical mouldings that are more detailed and curved.” Also, you can use bulkier, more apparent hinges and hardware compared to a modern door where the hardware is often concealed as much as possible. “In classic doors, customers usually prefer more ornate hardware as well, such as handles with curves, versus more lineal lines for modern doors.”

For a Colonial or Classical Revival door, Ayala says her company generally doesn’t use a lot of panels. “We usually end up doing a two-panel door with a lot of glass in the top,” she explains, “because people tend to like a lot of glass.” In fact, she says many of the doors they make in that category will be either half or three-quarters glass on the top, with the bottom being two panels divided by a rail or, depending upon how the house is cladded, V-grooved boards. “If the entrance gets really ornate with the transom and sidelights, so it doesn’t need any glass in the door, sometimes the design will go with an all-panel door, but it will be a pattern of, say, three large panels on the top, then three small panels in the middle, then three large panels in the bottom, so as to break up the panel structure.”

Moreover, the frame-and-panel door has advantages that transcend architectural styles. Says Hendricks, “If the door is meant to look like a plank-style door for a church or university, in a Gothic style or an Arts & Crafts style, we have developed ways to basically hang planks on a structure that’s based on a frame-and-panel method of construction.” He explains that historically, the mortise-and-tenon, stile-and-rail frame method of building doors is often embedded in a plank-style door. “Whether partially concealed or totally hidden, it’s just a more durable method than plank-and-batten construction and maintains a much better seal in the opening.” Adds Pape, “There are manufacturers that try to make doors with cheaper methods, because mortise-and-tenon is expensive, but for exterior doors it’s definitely the best type of construction, so we keep to it.”

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.