Product Reports

Architectural Salvage for Period Homes

The practice of harvesting materials and parts from one building for new life in another is hardly new. Before the cost of labor eclipsed that of materials sometime in the mid-19th century, the usable lumber, stone, brick and metal in unwanted houses was recycled into other structures almost as a matter of course. In the 1890s, architect Stanford White was famous – some say infamous – for combing Europe for antique mantels, columns, and carved-wood paneling that he would incorporate into his interiors for America’s Gilded-Age nouveau riche – and at eye-popping mark-ups. Whether you call it salvaged, recycled or simply used, the market for “experienced” building components continues today for period houses, and in ever-changing ways, as this look at four popular materials shows.

1.) Tile Roofing

From asphalt shingles to metal sheets, most roofing materials are destined for periodic replacement – frequently after service lives as short as 15 years. However, one of the most recyclable of building materials is actually a traditional roofing component: ceramic tile. What makes tile roofing practical to recycle under the right conditions is its legendary longevity.

“Tile roofs in Europe have lasted centuries,” says Michael Lukis of Tile Roofs Inc. in Frankfort, IL. “Years ago, architects didn’t realize that typically, it is not the tiles that cause roof problems, it is the wearing out of other components – fasteners, underlayments and flashings.”

One of the advantages of salvaged tile is for repairs. “The roof is a highly visible part of a house,” adds Lukis, “but with salvaged tile you can exactly match old material in look, age and color so that a repair to a 1920s or ‘30s roof doesn’t look like a repair – and you may also save a bit of money.”

Lukis explains how even a spot leak produced by, say, wind-driven rain can, over time, work its way through 16 oz. copper flashing. “If a tile roof is leaking,” he says, “It is the underlayment that is failing.” Therefore, a leaking tile roof does not have to be abandoned; it can be repaired and restored by removing the tiles, renewing the flashings, underlayments and other components, and then re-installing the tiles. “I like to buy salvaged tile, but I also try to save roofs,” Lukis says, “so when someone asks if I’m interested in the old tile roof they plan to rip off, I wind up explaining how it can be repaired – even though I’m happy to sell all the tile to another customer.”

It is not hard to envision where the restoration of a period house may entail an entire re-roofing in salvaged tile, but Lukis says that he also sells large quantities of recycled tile for roofing brand new houses. He describes one client who bought 35,000 sq.ft. of tile freshly salvaged from an 80-year-old sanatorium. The rustic style tile (no longer in production) was exactly what the client sought for his new hunting lodge, and he easily expects to enjoy another 80 years of service from it.

When asked why someone would choose to roof a brand new house with salvaged tile – especially if they are not limited by budget – Lukis has a surprising answer. “Many people prefer the older clay color. Though manufacturers of new tile sometimes attempt to simulate this color with glaze, it is not the same.” In fact, trying to obtain tiles in historic colors – either for matching repairs or new work – is often a driver for salvage. Earlier finishes, such as a true fire flash (where compounds are thrown into a hot kiln) are not really made any more and glaze colors from the early-20th century are problematic to duplicate because the ingredients and processes do not comply with today’s EPA regulations. For this reason, Lukis’ company imports some European tiles in order to better match historic American tiles and patterns; they have also been successful in re-creating the green glaze popular decades ago.

A client or architect may naturally wonder if they can determine the quality of recycled roof tile. While Lukis describes one client who sent tiles to a lab for testing to ASTM standards (which they passed with flying colors), he says the better gauge is the track record right on the roof. “To stand up to the moisture and freeze-thaw conditions of northern climates,” he says, “roof tiles must have an absorption rate of 8% or less, otherwise in time they will exhibit flaking, breakage and other signs of failure. Therefore salvaged roof tile in good condition has actually been tested in the real world – a pretty sound indication that you have a good quality tile.” He notes that this kind of trial-by-usage has the advantage of testing every tile in a roof, while a new manufacturer only tests samples of a production run or lot.

Lukis says the salvaged roof tile business has been pretty steady even through the economic swings of the last few years – especially compared to new tile sales. While he does not see the appeal of recycled materials as a big driver in his business, he describes one client who, in building a large new house, made extensive use of used roof tile and was able to obtain a 30% tax credit. “The Internet has done a lot to educate people on salvaged tile,” he says “either to sell or to repair and use, and they are now far more aware of its value and possibilities.”

2.) Slate Roofing

Another recycled building material at home on period houses – and in the same league as tile – is slate. Whether new or used, the life expectancy of roofing slate is determined by the source from which it was quarried. According to Jack Jenkins at the Durable Slate Co., based in Rockville, MD, “Most of the slate we see is from the slate belts in Vermont and New York State, which last about 125 years.” He explains that slates from Buckingham, VA, have a life of around 175 years, and Pennsylvania HardVein and Peach Bottom slates (which are no longer quarried) stand up for 100 and 200 years respectively.

“When we reclaim slate from a building, we research the slate type, as well as when it was quarried and installed,” he says, “so we have a good idea of the kind of life that can be expected from a new installation.” As an example, he says they usually do not even reclaim Pennsylvania blue-black SoftVein slate because its life of 60 years or more is comparatively short. “In fact, some of the high-end slates are hard to find because, having such extraordinary lifespans and durability, they do not come onto the recycled market.”

According to Jenkins, the majority of the recycled slate market is for additions to existing slate roofs and major repairs, especially when a match in appearance and longevity is desired. “Slate is a rock, a very long-lived rock,” he says and, echoing tile, “what typically fails on a roof is not the rock but the underlayment.” However, he says that they also regularly sell recycled slate for entire new roofs.” What drives the choice of recycled slate over and above aesthetics? The opportunity to keep the roofing out of a landfill is a factor for some clients but the bigger appeal is usually the bottom line. Installation labor is the lion’s share of the cost of any slate roof, old or new, but Jenkins notes that using recycled slate can contribute a significant savings on materials – as much as 30% over new slate.

For all of the above reasons, Jenkins says, “There is a pretty strong market for recycled slate,” with his company keeping an inventory of some 800,000 to a million pieces in stock. Also, he says they are tapped into a national network that makes it possible to source pretty much any slate desired, from graduated slate to green, purple and mottled slates and the always hard-to-find red.

In another bit of roofing déjà-vu, Jenkins adds that the recycling process is actually an advantage. “Because recycled slate is being handled quite a bit during the course of recovery, sorting and shipping, you are getting a pretty solid material by the time it arrives at a new installation site.” As with any building material, when ordering new slate you have to factor in some overage for waste. “It’s the same for recycled slate,” he adds, “but maybe only by a couple of percentage points more.”

When it comes to installations, Jenkins says that in the hands of an experienced roofer, there are no significant differences between installing recycled slate versus new slate. “However, we have been encouraging people to consider the hook system rather than using nails.” As he explains, hooks have been used for generations in Ireland and Wales. “Typically, under-nailing or over-nailing is one of the major sources of problems in slate roofs,” he says, either causing breakage of under-slates or punch-through on over-slates, “and the hook system eliminates that possibility.”

3.) Brick and Stone

Perhaps no building materials have as long a history of being recycled as brick and stone, but for period houses the market is about much more than used, run-of-the-mill masonry units. For example, John Gavin at Gavin Historical Bricks says that a large portion of his business is in paving – stones as well as bricks. Typically these come from urban streets to be repurposed by residential buyers for driveways and walkways, however, there is also the occasional call from a city that wants to repave a byway either with historical accuracy or for cobblestone ambiance.

Blocks crafted from granite or durable regional stones like quartzite and bluestone are hard to mistake for anything but paving – especially when they are worn smooth from generations of use – but when it comes to laying roadways you can’t use just any brick. “Paving bricks are heavy, dense and can take exposure to moisture,” says Gavin, making them tough enough for traffic as well as weather. “Purington was once the largest maker of paving bricks in the world,” he says, “shipping all over the globe until the post-war era, when blacktop led to the demise of paving-brick makers almost overnight.”

Used brick has a long history of being an economy building material, but that is not the end of the market in which Gavin’s typical client – or Gavin himself – operates. A big part of his business is supplying matching brick for building additions, both residential and non-residential. “We just had a call from a client in New York, where the local historic review board said they have to use matching brick or they won’t be able to proceed with the addition.” He adds that he suspects this will be a growing trend as historic regulations increase in sensitivity and people invest more in existing buildings.

While the bricks Gavin deals in may be from the golden age of brick-making – that is, about 75- to 120-years old and machine-made – the units themselves are far from ordinary. “We are constantly on the look-out for specialty bricks – products such as iron-spot brick or scratch-block brick – because this is what our clients seek.” For example, he says that not only is garden-variety, common brick not hard to find – “There are scores of old mills and warehouses in the Southeast built with this red-orangey brick,” – this is not the brick that is challenging to match on, say, a house addition. The same applies to the yellow brick endemic to the Chicago area.

Someone building a new house might seek reclaimed flooring for its aged character, or to gain environmental peace of mind by saving it from a landfill, but with brick it is more about blending. “Some clients want to get LEED points for using recycled materials,” Gavin says, “but we do a lot of work with architects who need to get matching brick for an addition.”

For this reason, he concentrates on the distinctive. “We are a high-end brick business,” he says, with “millions upon millions of pounds of material in inventory.” Gavin deals in clinker bricks too – the misshapen culls that became popular as visual accents in house and garden walls, especially in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. They are something of a specialty item he notes, and he sources them in old walls as well as from new suppliers.

Whatever the brick, typically the shopping process is pretty straightforward. The client will send a photo and dimensions of the desired brick or stone, and if Gavin has a match – which is likely – he will send back a sample. Orders are then shipped out on flat-bed truck. “I had a load of one brick type in the yard for five years, untouched,” he says, “then one day an architect called, asking ‘Do you have anything like this?’ and I sold the whole pile.”

4.) Architectural Hardware

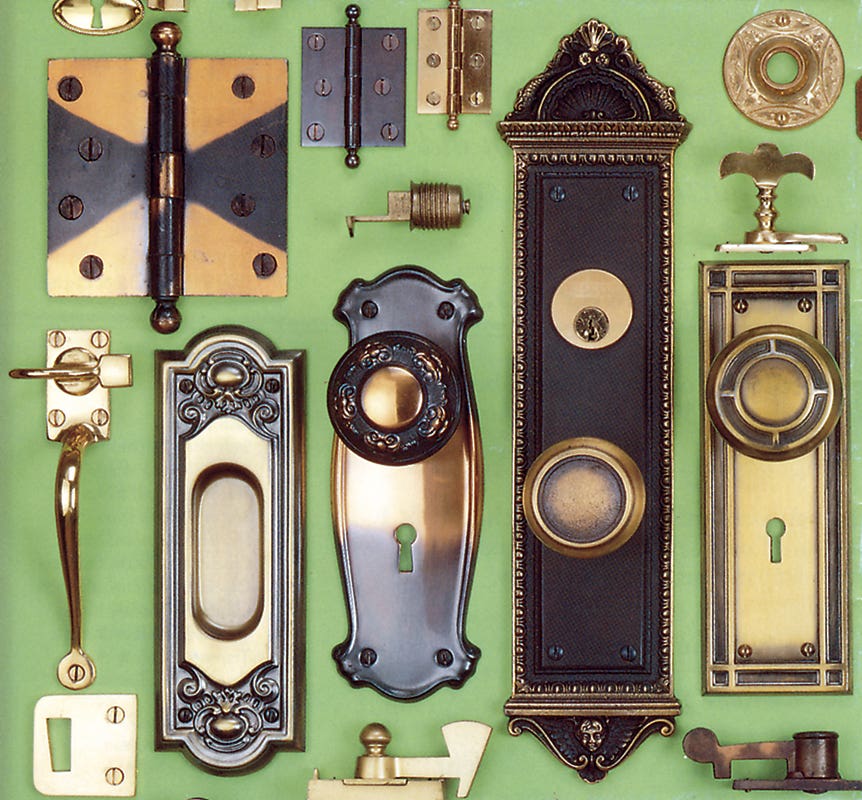

Though it too has a long history, architectural hardware is sort of an under-the-radar market in the recycled building parts world because the sources are so disparate – from general salvage dealers and architectural antiques purveyors to flea markets and now eBay. Nonetheless, with careful sourcing, recycled door locksets, knobs, window equipment and the like can be great assets for a period house project.

According to Bill Rigby at Wm. J. Rigby Co. in Cooperstown, NY, who specializes in unused original stock as well as antiques, they do a lot of business in relatively small items, such as sash lifts and other window hardware, but they see a significant call for many larger items that are otherwise unavailable as new products. Pocket door hardware is a prime example, including rabbeted locksets for mating doors and sheaves and rollers for top- or bottom-rolling doors. Rigby adds that, “Industrial salvage has gone through the roof.” By that, he means heavy-duty door handles, lights with cages, and items with the maker’s name visibly cast into it, “anything that can be repurposed for a house,” he says.

Recycled architectural hardware, however, is not like buying new. “The problem today with salvage hardware is that people will buy something because it looks pretty,” says Rigby, “but then find it is not in working condition.” This is typically due not to a lack of ethics but more that the buyers – as well as the seller – are not experts in hardware. A generalist purveyor might be selling everything from millwork and doors to staircases and lights; the same is true of eBay, where much salvage commerce is now transacted, but by anyone.

Rigby also notes that other pitfalls are investing in hardware that is not equipped to do the job the buyer expects – say, an office door lock that is attractive but not up to modern security needs – as well as buying items that are worn out or not complete. “Even door knobs,” he says, “should be a matched set of knob, rose and escutcheon and thimble, otherwise they won’t work or will wear out prematurely.”

Another common expectation issue is when buyers want to make hardware do something it was not designed to do. He notes how lever handles are increasingly popular – in part for ADA reasons. However, he explains that, “Ninety percent of old hardware is designed for knobs, and you cannot simply switch over to levers; the locksets are typically not built with sufficient springs and the shafts may not be correct.” He adds that while springs may be easy to fix or replace when broken, just shipping the lockset back and forth adds to the cost of the item. With this in mind, Rigby’s prime advice is to ask the seller about their return policy. “In a lot or order of several items, you are almost guaranteed to have one item that is not up to snuff.” PH

Gordon Bock is co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com) and available for keynote speeches, seminars, and workshops through www.gordonbock.com.

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.