Product Reports

Traditional Kitchen Cabinets

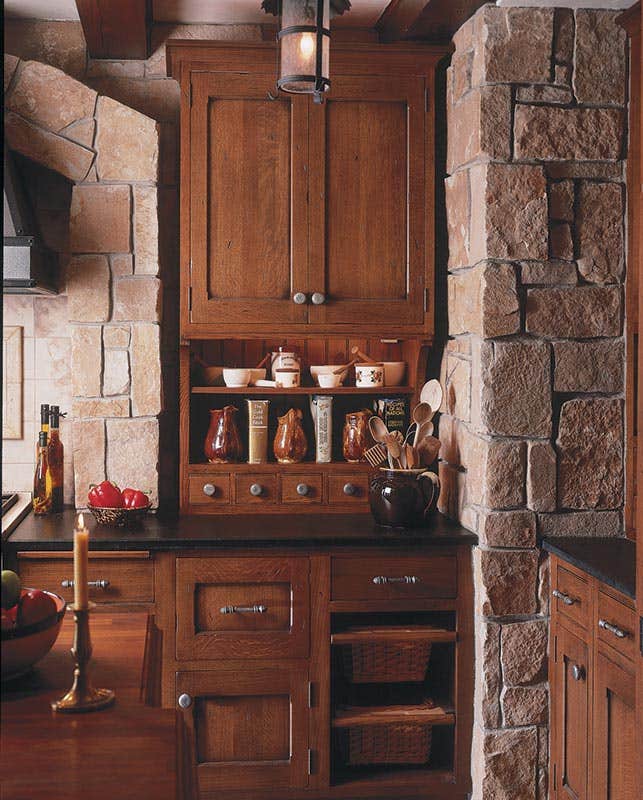

For many people, kitchens for period houses pose a puzzle: How best to make the space resonate with the building’s historic era or architecture, but also fit modern lifestyles? The challenge gets tricky considering that, even if a homeowner wanted an authentic kitchen from the 1880s, 1910s or 1940s, in most houses any evidence of an earlier appearance is long gone. One solution to this conundrum often lies in the cabinetry. Since cabinets are prime components of today’s kitchens, yet have a rich history of details that can be readily mixed and matched, they are an ideal way to help key a kitchen to particular historic ambiance. Here are some ideas from the pros on how to do it.

What Makes Cabinets Traditional?

The good news is that cabinets built with historical features are a growing interest in the kitchen industry with appeal beyond folks who embrace history. “The kitchens we see have been done over once already – sometimes twice,” says Mark Krueger at Plato Woodwork of Plato, MN, “and clients often call us to improve a ‘remuddling.’”

Another perspective comes from Sherri Cook at Cook and Cook Cabinets of Scarborough, ME. “While flat, modern, frameless cabinetry clearly has a strong market, the clients that come to us are typically looking for the traditional, inset cabinetry that is our specialty,” she says.

“We’re always working with period homes, but recently more houses from the 1930s, ’50s and even ’80s remodels,” says Carole Stevens at Crown Point Cabinetry of Claremont, NH. And in Montour Falls, New York, Vincent Chicone of Chicone Cabinetmakers, says, “We see a renewed interest in mid-century Modern design, reminiscent of the sleek lines of European-style cabinetry, and in the last few years, the popularity of simple and clean lines also extends to traditional, painted, face-frame cabinets.”

That being said, what makes a cabinet traditional? Turns out it begins not with details or materials, but with the basic woodworking DNA. Prior to about 1960, kitchen cabinets were typically built with face-frame construction – that is, a matrix of horizontal rails and vertical stiles attached to the cabinet box that adds strength to the front, supports doors and drawers, and finishes the spaces surrounding them. “When it comes to creating a period cabinet look,” says Krueger, “face-frame is where it starts.”

Another classic cabinetry feature that has ebbed and flowed over time is inset or recessed doors and drawers that close flush with the face frame. According to Stevens, “recessed doors and drawers that are in the same plane with the cabinet face are definitely key for traditional cabinet design.”

Krueger says his company is known for its inset look, and Cook too says that recessed doors and drawers are what clients desire and where they excel. Even within such minimalism, there are ways to vary the appearance and add interest. “The profile of the door, the shape of the moulding and the style of the hardware are all design choices that contribute to an overall period look,” says Stevens.

In contrast, the once ubiquitous overlay doors and drawers (where the door closes partially into and partially over the face frame) now represent their own segment of the market. Krueger says his company did a lot of overlays 25 years ago, but that it pretty much tapered off as inset doors grew more popular. “However,” he says, “occasionally we do see lipped drawers combined with inset doors for the Shaker look.”

Complexity and Contradiction

Simple, clean lines, in fact, are growing drivers of cabinet design. “We offer a wide variety of profiles for doors and drawers,” says Cook, “and over 50 percent of the cabinets we build use beaded inset frames, but the closest thing to a trend we have seen with inset cabinetry is to keep the recessed panels flat, and the inner profiles square – that is, not have us bead the cabinet frame.” This, she says, creates a sleeker, more contemporary look.

Krueger concurs and says, “We’ve seen a shift away from carvings and inlays to a much ‘cleaner’ look.” He notes that bead-board, once the instant touchstone for a Victorian or farmhouse ambiance, still comes into play for some kitchens, “especially at the backs of cabinets, but not so much in panels or in doors.”

Moreover, the trend in traditional cabinets in general has been to avoid complexity. “Five years ago, we would see elaborate details, such as ornate crown moldings,” says Chicone, “but now designs are very simple.”

“People are moving away from useless features,” says Stevens. “Small details, such as pigeon-hole drawers, are definitely not seen as much.”

Chicone says that interest in spice drawers has declined over the last decade. He reports even seeing people jettison those banks of 4-in. square drawers and repurpose the spaces to house wine bottles. “Wine storage seems to be something of a cabinetwork trend,” he adds, “though kitchens are not ideal places for storing fine wine long-term.”

According to Chicone, legged cases – a trend over the last decade that emulates the work tables and dry sinks once the only conveniences in kitchens – are still around, but with caveats. “Clients order false legs all the way down the cabinet, but they still want a toe space only four inches high. The reason is, while a higher space under the cabinet reinforces the furniture resemblance, it eats into the drawer and storage space above – a sacrifice few cooks want to make.

The Arts & Crafts Ethos

Perhaps the poster child of neo-traditional kitchens is the oaky, bare-wood Arts & Crafts-styled cabinet – which, paradoxically, was rare in kitchens of a century ago beyond a few architect-designed landmarks. Krueger says they see pockets in the country where they send Arts & Crafts cabinets, and they do a good amount of quarter-sawn oak cabinetry. Stevens concurs, noting that for her company, the cabinets are very popular on the West Coast and in the Midwest. Interest in the latter is so robust that her company has developed a Prairie Style cabinet line with strong Frank Lloyd Wright features. Straightforward as flat panels and unmolded frames may seem, she notes, “There’s a lot of knowledge and detailed design work that goes into getting them right.”

Cook agrees: “Because of the way quarter-sawn oak is cut, it is not available in wide boards, so panels were typically narrow. This was incorporated into the design of Arts & Crafts cabinetwork by using mid-stiles and increasing the number of panels for a given width.” Therefore she suggests that anyone looking for wider panels considers rift-sawn oak because the grain will allow for a more invisible seam where glue-ups are necessary.

Not surprising for a company based near an original epicenter of Arts & Crafts furniture, Chicone builds many of his Arts & Crafts-style cabinets from quarter-sawn oak, then finishes them with an authentic process. “We don’t use stains, just fuming,” he says.

And should evoking historic ambiance not be enough of a balancing act, meshing traditional kitchen cabinets with modern appliances is often where the rubber meets the road in a period kitchen. For example, do you try to make a monolithic Sub-Zero go away with woodwork? The answer, of course, depends upon the client and the equipment. With Chicone’s clientele, “No one wants to see any clue there’s, say, a dishwasher,” and they call on him to conceal conveniences behind panels and in boxes.

On the other hand, Stevens says that while wood panels are popular, less than 50 percent of their projects involve total concealment. “Some rooms have better balance without the use of appliance panels,” she says, noting that planning for appliances is key, especially when there’s interest in hiding them. “Clients need to be aware of what appliances work with panels, as well as what manufacturers and models do it well.” She notes that many refrigerators or dishwashers take panels, but some show stainless steel legs and edges or stand out obtrusively in a bank of cabinets. That is not to say that a good cabinetmaker will balk at projects out of the ordinary; indeed just the opposite is often true. Chicone no doubt speaks for his colleagues in the industry when he says, “You can make boxes all day long, but to have a client say, ‘We want to do something special’ – that’s when the fun comes in.”

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.