Product Reports

Historic Door Hardware

Doors would not be doors if it weren’t for working historic door hardware – that is, the hinges that allow them to swing open and the knobs and latches that hold them shut. Since historic door hardware is even older than America – yet one of the richest forms of the industry today – a quick rundown of the primary types, materials and terms can be valuable background for anyone shopping for historically appropriate fittings.

By Gordon Bock

All About Hinges and Butts

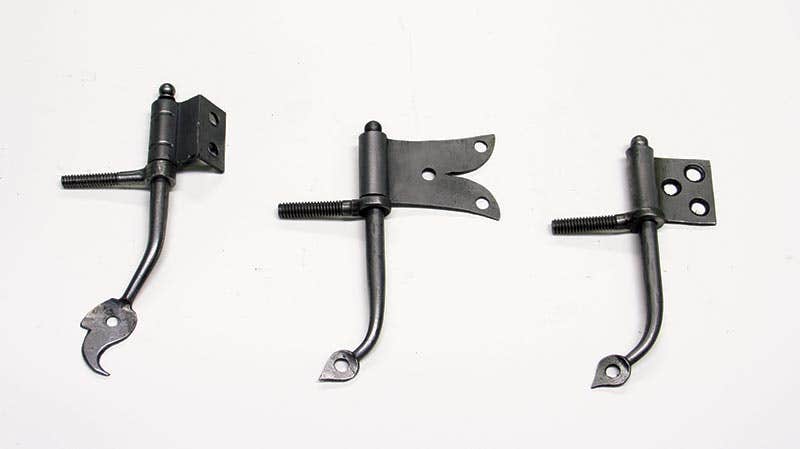

Wrought Iron.

From the Colonial era until the early-19th century, builders’ hardware was generally handcrafted from wrought iron (essentially pure iron) by blacksmiths along with fireplace equipment, nails and cooking utensils. In the case of hinges – which, in the pre-revolutionary era, might also be imported from England – their iconic appearance, little changed from medieval times, derived more from traditional ironworkers’ techniques and motifs than any fashion or style.

Large hinges, for example, were typically “strap” or “hook-and-eye” types, where a long strap attached across the surface of the door swiveled on a simple upright hook or pintle. The pintle end might be fashioned into a spike for anchoring into the door frame, or it might extend into a projection called a rat tail that helped mount the pintle to the frame surface. Smaller doors and cabinets made use of H and HL hinges that, contrary to lore, were not references to His Lord contrived by pious Puritans, but simply ways to better distribute the load. Whatever the origins, Dave Mitchell of D.C. Mitchell in Wilmington, DE, notes that early hinges like the hook-and-eye type “were certainly easier to make than true knuckles.”

Cast Iron.

Shortly after the Revolution, doors across the new country began swinging on the ubiquitous hinge of the 19th century – the cast-iron butt. As early as 1923, architectural historian Henry Chapman Mercer noted that, after being invented in England and patented in 1775, cast-iron butts rapidly superseded wrought-iron hinges because they were readily available and affordable. Though cast iron had its drawbacks for working hardware – it was brittle and prone to cracking if twisted or poorly installed – the metal was not only easily mass-produced from molds, but it also readily took on complex shapes, such as the characteristic relief patterns on the leaves or multiple knuckles that shared the load better than lift-off hinges. Though cast-iron butts were generally always considered economy hardware with limited decorative appeal compared to brass or bronze, starting in the late-19th century, better grades could be ordered in Bower-Barff – a complex, proprietary surface treatment that produced a black, “rustless-iron” finish. Cast iron was also the metal of choice for large doors because it was less prone to wear at the joints than steel butts.

Bronze and Brass.

Dense, corrosion-resistant and readily formed into intricate, delicate shapes, bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, and brass, its zinc-alloy cousin, have been used since at least the 17th century for casting architectural hardware, but these products were often limited or imported until an American hardware manufacturing industry began to take hold. However, by the early 1830s, the popularity of the Greek Revival style, as well as burgeoning economy and the advent of the Industrial Revolution, helped move door hardware away from handcrafted wrought iron to mass manufacturers, such as the firms of Mallory Wheeler (organized in 1834), or Russell & Erwin (begun in the 1830s as producers of plate locks). Bronze soon became the premier metal for butt hinges, especially for the large, ornate hinges used in the latter-19th century.

Not only did houses of the 1870s and ’80s often employ massive doors that required heavy hinges to support them, but these doors also often went hand-in-hand with high, thick baseboards that demanded extra-deep, “wide-throw” hinge leaves – as much as 5 in. across – in order for doors to swing clear of trimwork. Bronze ably filled not only these mechanical needs but also the newfound taste for ornament ignited by the Aesthetic Movement that led to casting all surfaces of hinges in sinuous, incised decoration – whether exposed to view or not. Elliot Lowe, president of Lowe Hardware in Rockland, ME, says, “The biggest trend we see in traditional hardware is not changing the designs but tweaking them – particularly the proportions or scale.” Lowe, whose company is machine-shop and CAD-based, also says, “Recently we’ve been reproducing historic hardware that was originally cast.”

Steel.

As the age of steel advanced in the late-19th century, it was inevitably applied to door hardware, making the steel butt hinge the dominant door hinge by 1910. Rather than being cast, steel butts of a century ago were forged – that is, stamped and formed by machine. While this process made the hardware even less expensive to manufacture than cast-iron butts, it also made it less decorative, with hinge leaves that were inevitably smooth-faced and unornamented save for the characteristic round ball tips on the pins. Unbreakable as they were compared to cast-iron butts, steel butts were relatively soft, with a tendency to wear at the joints and sag under the weight of large doors. The solution of manufacturers was to fit the knuckles of high-end hinges with ball bearings or hardened steel washers.

All About Knobs and Latches

The earliest doors in America were commonly opened not by twisting a knob or lever, but by depressing a thumb-latch – an ingenious device still used today. One of the jewels of hand-wrought hardware, thumb-latch design varied according to place and time, but followed a basic five-piece form of 1) semicircular hand-grasp, typically terminating in club-shaped end-plates or “cusps”; 2) thumb-lever that, when pressed, raises the 3) latch bar on the other side of the door; 4) staple or bar pivot; and 5) notched bar that serves as the bar catch.

Hand-wrought thumb-latches appear to have been made domestically, or imported from England, until about 1800, when they were gradually overtaken by factory-made, improved versions, such as the Norfolk latch (which mounted the hand-grasp to a plate) and the Blake cast-iron latch (patented in 1840).

Though thumb-latches continued to be used well into the 19th century, by 1800 a well-to-do homeowner could also open a door by turning a knob. Despite the rich variety of other door hardware in the 19th century, manufacturers clearly tried to outdo each other in a quest to make knobs out of the most novel materials or inventive processes. The result is a cornucopia of historic knob types that has fostered today’s vibrant doorknob collectibles market.

Brass.

In the first quarter of the 19th century, surface-mounted wrought-iron locks might be activated by relatively small, simple brass knobs as well as thumb-latches. Made in both round and oval shapes, and mounted to hand-wrought spindles, these knobs may also have been gold or silver plated in expensive homes. “Many people assume that early brass doorknobs were heavy and solid – in part because some modern Colonial versions are made that way,” says Bob Ball, a partner at Ball & Ball Hardware in Exton, PA, “but the originals were actually light and hollow, because brass was close to a precious metal.” In the same way, Ball notes that modern Colonial knobs have much thicker necks than seen historically: “Spindles in the 18th century were hand forged, then the knobs were cast around them, so the spindles are narrow and tapered where they go into the knob.”

Glass.

As the domestic glass industry expanded in the second quarter of the 19th century, glass manufacturers saw glass knobs as a new market. Made of cut or pressed glass, these knobs were attached by running the spindle through the center of the knob. Silver-colored mercury-glass knobs were in use by the mid-19th century. Glass knobs achieved new status in the early-20th century when their sophisticated cut and pressed designs, as well as improved methods of mounting them without running the shank through the glass, lifted them to the upper ranks.

Wood.

Always the most cost-effective option, knobs turned from hardwoods – typically in a barrel or ovoid shape – then stained or left natural, remained ubiquitous into the 20th century.

Pottery.

First appearing in the 1840s, and possibly patented a few years before (many early patent records are lost to fire), knobs made of ceramic-like materials became the workhorses of door hardware, albeit garden-variety in design. Ovoid in shape and highly glazed, they came in three general styles: mineral (dark brown), jet (black) and porcelain (white).

Cast Iron.

An expedient substitute for brass and bronze, cast-iron knobs were typically cast with an ornamental surface, and could be plated in bronze for an affordable alternative to the more expensive metal.

Stamped and Hollow Bronze.

By the 1860s, the creativity of the age of invention combined with the Industrial Revolution and an appreciation for quality to produce highly decorative bronze knobs with deep relief designs that are still revered today. “The Metallic Compression Casting Company of Boston was one of three companies who really advanced the manufacturing of hardware in one leap,” says Rhett Butler, president of E.R. Butler in New York City. As Butler explains, “In MCC Co.’s process, the metal was forced up into a die – almost a cross between casting and forging.” Examples of their work, such as the Ludwig Kreuzinger-designed “doggie doorknob,” remain pinnacles of the knob-makers’ art, with collectible originals commanding hundreds of dollars.