Product Reports

The Lore of Traditional Lantern Design

What drives the design of light fixtures has long been a chicken-and-egg question. Be it mechanical necessity or aesthetic ambition, the answer is even more elusive for lanterns – those translucent cases historically used to protect exterior lights. Before electricity and gas, open-flame lanterns in various forms lit the way from street to house while perched on posts or hanging from walls or porch ceilings. Since lanterns are one of the most popular types of outdoor historical lighting, but among the least documented, it is useful to explore where these timeless fixtures might have gotten their design DNA.

The mystery of traditional lantern design is compounded by the fact that most early lanterns are lost to history. “It’s rare to find original, very early exterior lighting intact,” says John Ehrlich of The Federalist in Greenwich, CT. “The fixtures were often made of materials, such as tinplate, that do not hold up forever, plus the heat and byproducts of the light helped disintegrate them.” He adds that while “there are not a lot of records on early lighting,” with catalogs uncommon until the mid-19th century, his company does research designs in early graphics with street scenes, such as those by Paul Revere.

When good fortune shines, however, it can sometimes beam an historic lantern to one’s door. According to Michael Krauss of Authentic Designs in West Rupert, VT, “A number of our designs come from fixtures brought in by customers who ask us to make a duplicate or multiple copies for their own clients.” He adds that provenancing such fixtures sometimes leads to interesting places. For example, upon researching a pendant fixture from the Cornish, NH, home of sculptor Augustus St. Gaudens, they found an earlier copy in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI.

Historic fixtures have also been the inspiration at Brass Light Gallery in Milwaukee, WI, because, as Margaret Howland explains, “We got our start selling vintage and antique lighting.” For example, a lantern series in their product line may start with an original fixture made for gas or candles, but then get scaled up or down for different applications (walls, posts) as well as modern illumination. “Sometimes the vents that would have been functional in the original are now closed off for UL safety reasons,” she adds. In other cases, Brass Light too turns to early graphics, such as 17th-century paintings.

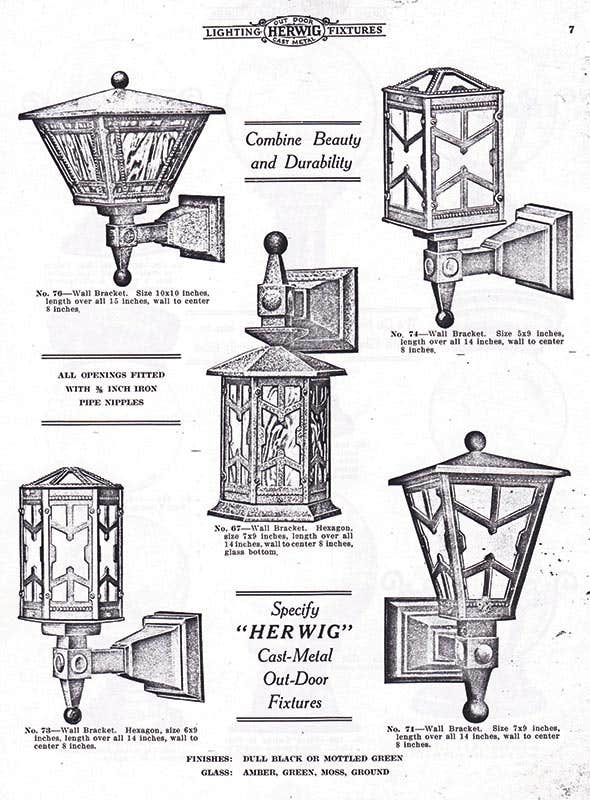

Interestingly, at Herwig Lighting in Russellville, AR, the source of many historic designs is the company itself. As Don Wynn explains, “At the turn of the 20th century, our founder, Bill Herwig, went to Europe and studied eight-sided, six-sided, and four-sided lanterns, and began casting his own versions here. He would also take orders and designs from architects and build to suit. Many of these are in our catalog today.”

In Search of Illuminants

What we do know with certainty about early lanterns is the history of pre-electric light sources – that is, the parade of gradually improving fuels for a burning flame. The earliest are candles that, well into the 19th century, were typically made of tallow (animal fat). Though inexpensive and readily available, tallow candles had a tendency to collapse when warmed by the heat of the flame, so lighting devices of the era, from candlesticks to lanterns, were made with characteristic tubes that supported the candles. By the 1830s, tallow candles were being superseded by spermaceti candles (made from wax from the heads of sperm whales), that were stiffer and burned brighter with less flicker.

The whale trade brought not only better candles, but also clean-burning oil rendered from blubber. Whale oil was the gold standard of lighting from the mid 1700s into the 1850s, but its growing cost spurred a search for more economical fuels. Alternatives to whale oil included lard, camphene (redistilled turpentine) and burning fluid – a volatile concoction of alcohol and turpentine that exploded under the slightest pressure. Better fuel then became critical for lanterns not only for light output and economy, but also for safety because lanterns, in most early cases, were also portable.

Howland notes that before early street lighting, which probably first appeared in urban areas after 1700, people relied on hand-held lanterns lit by candles. “They carried them from place to place,” she explains, “so a lot of historical lanterns have hooks that, while they may be non-functional, are still part of the design.” Ehrlich agrees: “For example, the tops of many lanterns are fashioned into a large bail or strap so the lantern could be lifted with a shepherd’s hook.” He adds that, in the same way, the fanciful mushroom tops with holes in them are made to allow heat and gasses to exhaust. Krauss notes that the same is true for the coach lamp – that ubiquitous Colonial Revival totem guarding countless doorways. “That projection at the bottom was designed not only to hold the wick, but also to be a handle so that you could carry the lamp from your carriage to your house,” he says.

Whether produced by candles or oils, open flames might work naked indoors, but outdoors in lanterns they would quickly succumb to draughts and wind, so protecting the flame became paramount – yet tricky. “Glass was once very costly,” says Ehrlich. “In fact, so prohibitively expensive for very early lanterns that they used mica.” When glass was eventually lavished on lanterns, it was not without some extra precautions. “The criss-cross design, which is seen so much, was devised to protect the glass,” says Ehrlich, “and is laborious to produce even today.”

“We make a traditional chandler’s lamp that has the characteristic wire guard around the globe,” says Krauss. “Since a chandler sells ship’s supplies, it makes sense he would want that protection in his lantern while working around flammables in the warehouse.”

Though matrix-like grids and guards evolved to protect large panes of glass, in some lanterns the reverse is true. “At the turn of the 20th century, there was a fashion for Tiffany-style glass in lanterns,” says Wynn. “Since this is composed of many pieces of glass soldered into a lead frame, Bill Herwig devised a glass backup to improve on the design.”

The Ken of Kerosene

Another thing we know for certain about lantern design is the influence of kerosene. A petroleum product developed just before the famous Drake oil well of 1859, kerosene was more affordable than whale oil and safer than burning oil. It also produced a steady light, due to a new flat-wick burner and glass chimney, which quickly made it the premier lantern fuel well into the 20th century.

Kerosene appeared at the first flush of the Industrial Revolution, and while most light fixture manufacturers adapted their products to burn the new fuel, the name that is most connected with kerosene is Dietz. Established in 1840 as Dietz, Brother & Co. of New York by Robert E. Dietz, the company had become highly successful manufacturing and importing decorative oil lamps when Dietz took off in a new direction in 1874. Perhaps a prescient businessman who saw the coming growth of railroads, he abandoned decorative lamps and switched to making the inimitable, portable, utilitarian lanterns still used in industrial sites and campgrounds today.

Dietz was already venturing into kerosene lanterns in its 1860 catalog (one of the very earliest such documents) when it offered a classic street lantern featuring four tapering sides with keystone-shaped glass panes, one of which was a door. The top featured four more glass panels, though with a shallower pitch and topped by a circular ventilator. Inside was mounted a kerosene lamp replete with glass chimney. Equally iconic is the Dietz station lantern: a rectangular box with three glass sides and a metal back, top and bottom that was designed to hang on a wall or be carried by a handle attached to the ventilator on the top. The large lamp concealed inside was backed by a circular mercury glass reflector. More interesting perhaps is the Hexagon Taper Lantern, which has six long, tapering sides and a relatively flat top. Here, the lamp reservoir is actually the base of the lantern with the burner and chimney poking though the bottom. Also noteworthy is the Sugar House lantern: a boxy frame with three glass sides and concave “roofed” top supporting some sort of circular reflector around the top of the lamp chimney.

Robert Dietz died in 1897, but a year later Dietz-style oil lamp designs were appearing in the “Cheapest Supply House on Earth” – that is, the catalog of Sears, Roebuck & Co. Among the lanterns depicted were three Globe Tubular Street Lamps meant for either mounting to posts or hanging by a bail handle. Elsewhere called Pioneer Street Lamps, these are the legendary lanterns of westerns and rural townscapes with pear-shaped glass globes, metal frames and conspicuous hat-like tops. Most interesting though is the four-sided Square Tubular Street Lamp, for use “in front of lodge room, store, or church” that, though marketed for 1890s kerosene, looks right out of the whale oil era. As Ehrlich notes, “In England, early designs were often perpetuated regardless of advances in light sources because, as lanterns deteriorated, they were copied, and then copied again.” Apparently, no less was true on this side of the pond.

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.