Product Reports

Finely Wrought: Reproduction Hardware

As research and experience heightens our knowledge of the past, demand for accuracy in the products that we select when restoring or duplicating historic architectural elements has increased. Reproduction hardware is no exception. For decades, restorers and preservationists have had to either make do with inferior replicas or scour the Eastern Seaboard for salvaged hardware. And today, the standard-issue chain-store hardware selection often crudely emulates the finely worked metals of the past. While much of the more commonly available early or “Colonial” reproduction hardware we see is cast or stamped, those seeking and appreciating authenticity seek out goods that have actually been individually worked in a forge by the hand of a blacksmith.

From the Forge

All iron is not alike. While much of the hardware we see today has been cast, it is wrought iron that is considered superior for several reasons. Aside from an inherent greater strength (the act of melting iron into liquid form destabilizes its structure and makes it brittle, especially in extreme cold), the detail available in handwork possesses many subtle nuances in form and finish that casting does not permit. This is to say nothing of the infinite variation from piece to piece in hand-wrought hardware that imparts the flavor of authenticity. Wrought pieces are often thinner and lighter in weight than their cast cousins, as well as more flexible and resilient. Under strain, wrought iron will flex, while cast iron snaps. Mending a shattered piece of cast iron is extremely difficult – as any welder will inform you – as it tends to “burn off,” unlike a forged piece.

Another advantage to wrought iron is that its composition inhibits rusting. “Wrought iron, though not as hard as steel, did have a quality superior to steel in that it resisted rusting due to its silica, or glass, content,” notes Pomfret Center, CT-based Fagan’s Forge’s web site. “The silica arranged itself in thin layers in the wrought iron and restricted the formation of rust.”

Hand-forged hardware is most apparent as large strap hinges on outbuildings. Although they may initially look similar to farmers’ supply pieces, the nuances of hand-forged items impart a much more historic look to a building. Donald Shaw, president of Fagan’s Forge, states that “We specialize in strap hinges, using mainly the Bean or Spear designs. These are two patterns that have been made for hundreds of years.” To maintain a ready supply, he adds, “Our hardware is made in India, where there are still some very skilled blacksmiths in business; unfortunately, fewer and fewer blacksmiths can make a living today in the U.S.”

Barns and period-style outbuildings are a large portion of Shaw’s clientele. “Today, people are often building barns instead of garages,” notes Shaw. “As people grow older, they and their kids have accumulated stuff they don’t want to throw away, and mom and dad’s barn is the perfect place to store everything. Our other principal clients are people building accurate reproduction Colonials, although this market has lessened somewhat as the Victorian market has increased.”

To complete the well-finished barn, Fagan’s Forge also offers a large-scale Swordfish latch to secure the door to its surround. Barn hardware is not Fagan’s sole offering; the firm also stocks shutter and cabinet hardware, as well as fireplace accessories.

One contemporary American blacksmith who is flourishing is Franklin Horsley, manager of the Old Smithy Shop in Brookline, NH. Horsley personally creates hand-forged, sophisticated, “high-style” pieces that are the highlight of a period building.

Just as the village smithy of days gone by was called upon to fabricate even the smallest piece of hardware, Horsley produces a seemingly endless selection of hinges and cabinet hardware built around such subtleties as the authentically narrow barrel hinges instead of the contemporary wide-barrel ones.

These exacting replicas are authentic down to the hand-hammered smooth finish found on the best ironwork of the 17th, 18th and early-19th centuries. Known especially for his Suffolk and Norfolk latches, Horsley can also replicate existing antiques on a custom basis.

The Old Smithy Shop is hardly limited to door hardware, and also creates replicas of a variety of fireplace cranes, trammels, trivets and cooking utensils. A reproduction fireplace crane is a favorite of Horsley’s; it is especially popular with those whose large, Colonial-era dwellings are missing this essential item.

Beyond Colonial Hardware

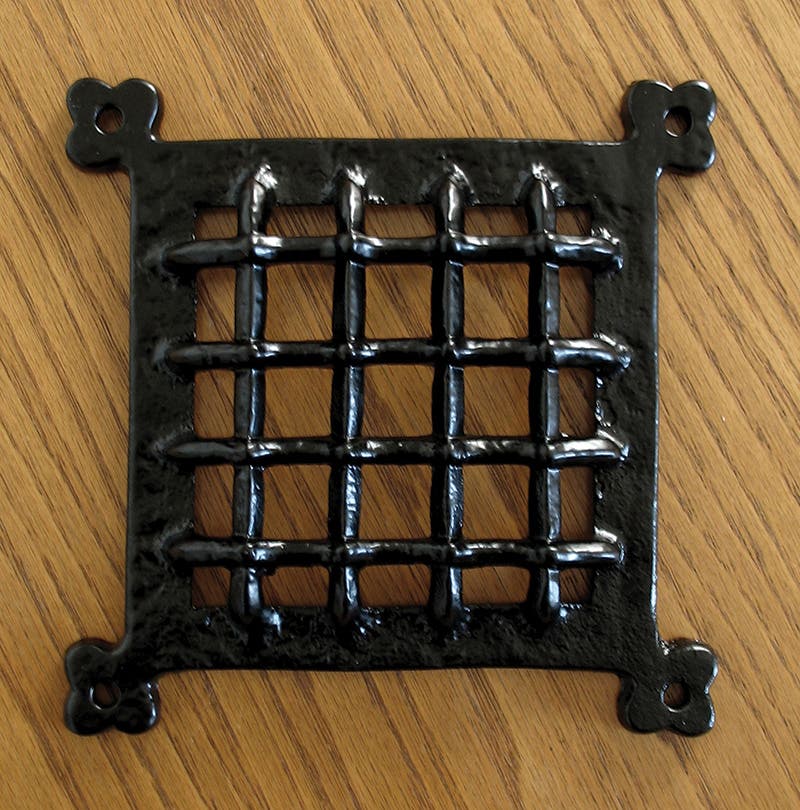

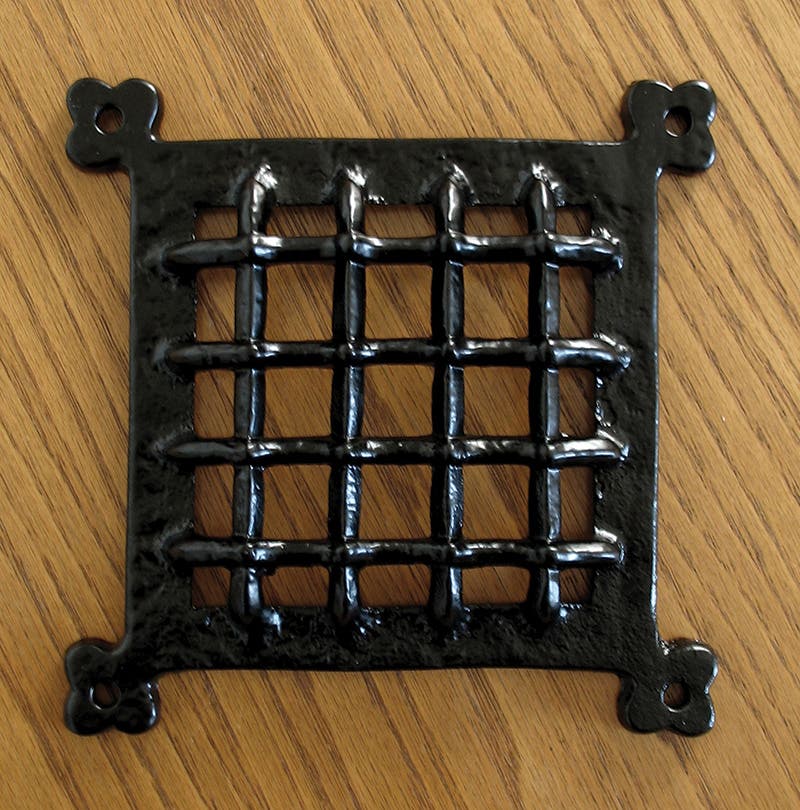

Not all historic ironwork being reproduced today is based on Colonial work; Maguire Iron Corp. of Richmond, CA, also offers an extensive line of European-influenced designs, including Medieval-inspired patterns that coordinate with the resurgence of the Arts-and-Crafts movement and Mediterranean Revival styles.

Rachelle Greenberg, manager at Maguire Iron, observes that “clients seem to be drifting away from the fancier pieces and towards simpler, less ornate hardware; they like the ‘beefy’ look of the Middle Ages.”

Continuing the trend of offering authenticity coupled with the ability to service clients continually pressed for time, Greenberg claims that Maguire Iron’s inventory consists of “pieces that are all hand-forged in the U.K. They’re made of malleable iron, and all based on historic patterns. All of our pieces are in stock.”

While Early-American hardware was fairly consistent in its coloration (black), European pieces had a much broader range of finishes. Maguire Iron therefore offers its wares in a variety of colors and metals. “We have our standard dull-black finish,” says Greenberg, “but also the armor-bright, a silvery metallic finish with black in the crevices, and a rust finish. All of these are then treated with a clear finish that protects them from degrading.” Maguire’s pieces are also available in brass or bronze by request. Another highlight of Maguire’s line is the fact that there are high-security locks available that are an integral part of each latch assembly. The firm also supplies cabinet and window hardware, as well as historic lanterns.

While most of us rarely spare a thought to how window shutters are to be properly hung (as evidenced by the vast number of incorrectly hung, vestigial shutters in this country), firms such as Philadelphia, PA-based James Peters & Son specialize in the well-hung shutter. Bearing such colorful sobriquets as Shell, Grape or Rat-tail, James Peters carries an extensive line of plain and ornate hinges and dogs that secure shutters to a structure with a combination of strength and authenticity.

One may wonder about the importance of using the more expensive wrought-iron pieces versus inexpensive cast iron, but with every job it is the individual details that create a cumulative effect and make for a believable restoration or re-creation; compromise often pushes a project down a slippery slope that may have started life as historic, but somehow winds up as a non-descript tract mansion.