Windows & Doors

Restoring Bronze and Steel Windows

North America is a land rich in wood, and wood windows, historically, have dominated, especially the iconic double-hung sash. Nonetheless, for over a century, windows made of metal – principally steel and bronze – have also been part of the scene, particularly for Classical, Romantic, and even early Modern architecture. They are worth understanding for anyone working today on an existing or new house built in a traditional style.

Bronze Windows

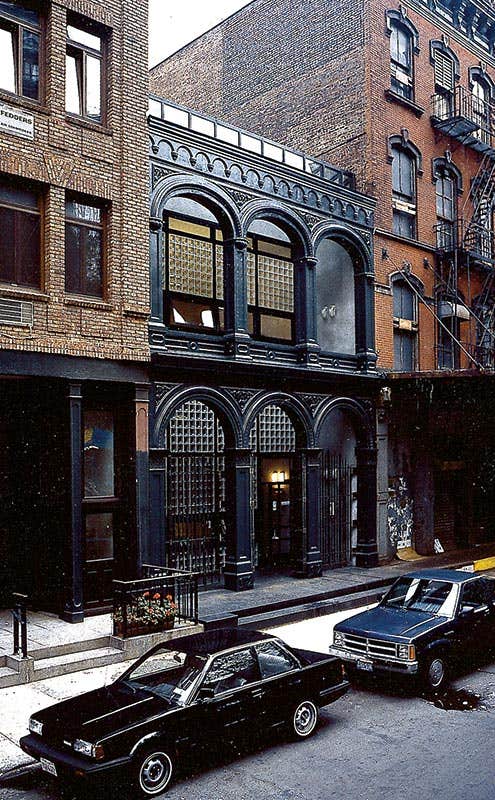

Bronze occupies a special place among traditional window materials. An alloy of copper and tin or other metals, bronze was being made even before the dawn of the eponymous Bronze Age around 4,000 BCE; still, it was rare in American buildings before the 1860s. While domestic foundries did produce some small-scale sculpture, bells and cannon, the first major bronze architectural pieces seen in America – the 1863 “Columbus Doors” at the U.S. Capitol – were imported from Germany. By the late-19th century, however, bronze was in wide use in public and commercial buildings for applications like grilles, teller cages, elevator doors and windows. “We’ve been building bronze windows and doors since 1990,” says Robert A. Baird, vice president of Historical Arts and Casting, Inc., in West Jordan, Utah. “And we kind of started while we were working on the Supreme Court Building in Manhattan.” Also called The New York County Courthouse, that 1913-27 Classical Revival building underwent several renovation campaigns in the 1980s and ’90s. “They couldn’t find anybody to replicate some windows, so they asked if we could do the job and, being game for something new, we said yes.”

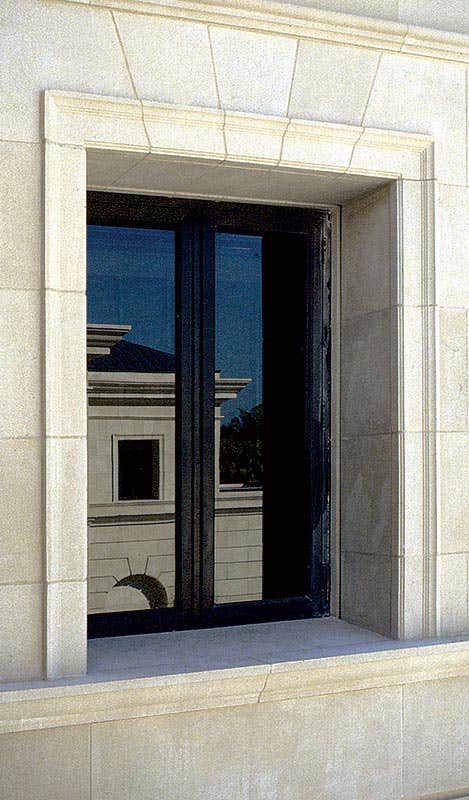

The appeal of bronze is both mechanical and architectural. Its ability to resist decades of weathering is legendary, but bronze is also strong – superior even to early wrought iron, and long the stuff of marine hardware, always high-end. By the heyday of the steel window in the 1920s, several manufacturers also offered bronze windows to serve the market for banks, government buildings, town houses and estate homes. For example, in their 1926 catalog, steel window manufacturer Henry Hopes & Son of London included a section for solid-bronze casements, noting that they “make all our sections in this metal.” Suppliers such as Newman Manufacturing in Cincinnati and Wm. H. Jackson in New York were even more dedicated to producing in this metal.

While prosaic steel windows waned after World War II, as aluminum got a big push, bronze windows continued to appeal to an upper-end residential market. Today, steel window manufacturers may offer their stock windows in other metals, but the specialized nature of bronze and the projects that specify it often put it in the custom or semi-custom category. For example, Baird says, “We have a whole line of standard products, but it is all built to order.” While he says they inventory the materials to build the products, “beyond having examples in our showroom, keeping windows and doors in stock is not practical.”

The expense of copper-heavy metal in a fluctuating market is one reason, but more critical is the reality that you don’t get architectural bronze appropriate for windows at a conventional industrial supplier of bars, angles and tubes. This can be a factor if the bar profile is special – say, for an exact historical reproduction – or if lead times come into play. “The big challenge is, if you want something that looks beautiful, you have got to have extruded material,” explains Baird, and that can be tricky to source. “We do get some bronze extrusions here in the U.S., but most come from overseas – Australia, Switzerland, Korea – and we are always developing new sources.”

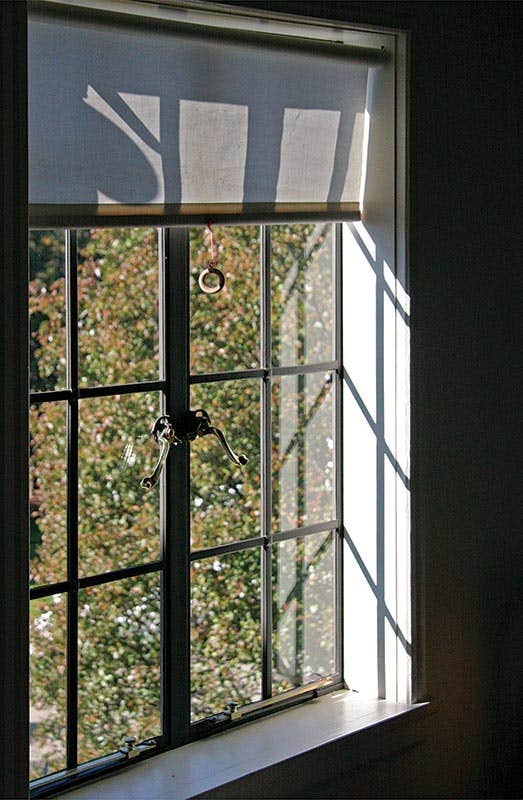

Whether it is wood, steel or bronze, part of the economy that comes from making a production window is achieved by not having to change tooling any more than necessary to accommodate a switch in design or materials. “The goal of most steel window and door makers,” explains Baird, “is to build everything they can with the profiles they have already established.” No surprise then why steel and bronze windows of the past often used identical rolled profiles for sashes and frames regardless of the metal. However, to meet modern needs for waterproofing and state-of-the-art glazing, Baird says, “Over the past 20 years, we have developed a whole series of extrusions to go with our systems,” which include, among other features, true divided lights. Indeed their designs range from classically oriented three- and eight-light casements to ganged windows with early-20th-century muntin patterns that emulate the Arts & Crafts work of Greene & Greene.

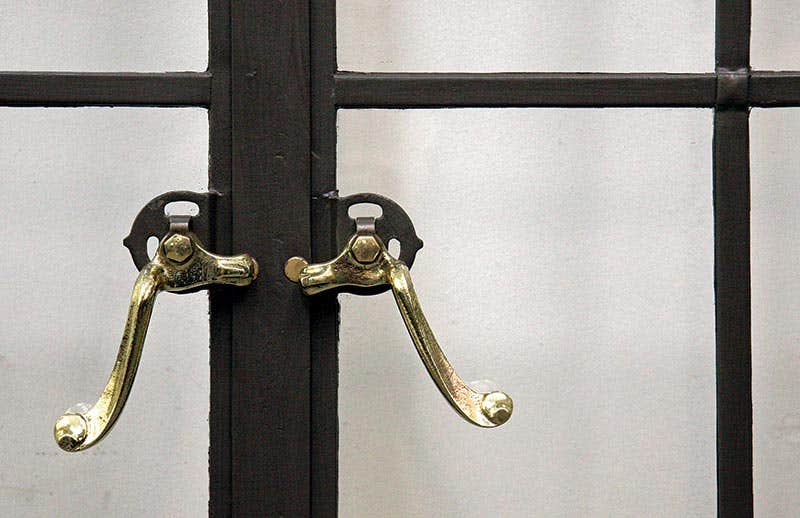

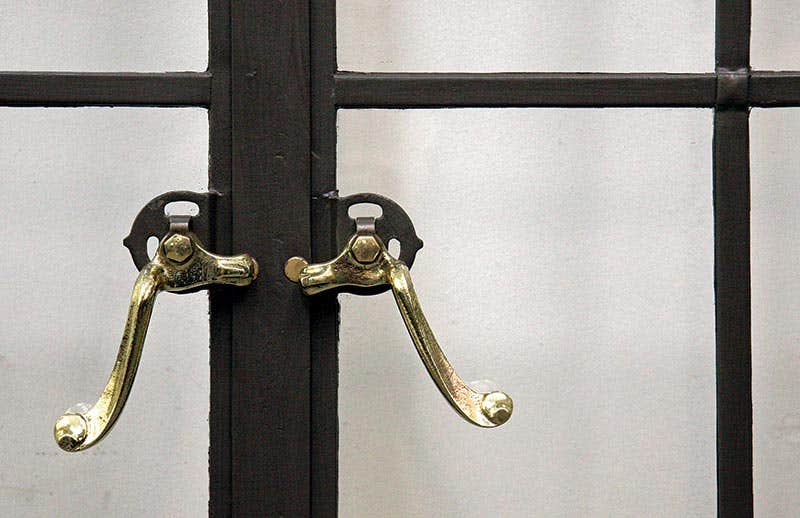

The considerations for bronze windows don’t stop with the sashes and frames either. Bronze is a heavy metal, and hardware – especially hinges – have to swing many pounds thousands of times a year. Baird notes that, customarily, window and door manufacturers buy third-party hardware for their products – even those making metal windows and doors. It follows logically then to look at the options for hardware when specifying bronze windows, making sure that the components are up to the job. “We initially used third-party hardware on our doors,” says Baird, “until it started to fail due to the weight, so then we started building our own.” Obviously, a bronze window that doesn’t open or close easily isn’t much good, no matter how beautiful it is.

Steel Windows

Ferrous metals in windows are foremost by dint of numbers. Though physical evidence of the earliest windows on this continent is scarce, tantalizing clues come from fragments excavated near Williamsburg, Virginia, including leaded-glass casements in iron frames. It is likely that such windows were imported from England: iron-frame casements are still found in 18th-century English houses, such as the Chichester County Hall by Christopher Wren. Thereafter, the record for steel windows is spotty at best until around 1900, when the use of steel windows took off – not only because they were considered fireproof (a big plus for commercial buildings in urban areas), but also by virtue of their economy and simplicity. The strength of the metal allowed for thin muntins, svelte sightlines and more open glass; by the time of the surging economy of the 1920s, steel windows were the darlings of the utilitarian building world.

By happy coincidence, in the 1920s, the English Revival styles became the new face of suburban America. And when thousands of blocks – even whole communities – became dotted with Stockbroker Tudors and ersatz Cotswold cottages, steel window makers here and in England stood ready to supply them with windows. Those windows are still in service today in recent additions as well as original installations, as many a period homeowner or designer can attest. “I’ve got more respect for those original steel windows now than when I started in business 38 years ago,” says John Seekircher, founder of Seekircher Steel Window in Peekskill, N.Y. “When all makes have lasted 70, 80, even 90 years, it must have to do with the quality of that early-20th-century steel,” he speculates; “it’s like old-growth timber.”

Repairing and Upgrading Metal Windows

Thus Seekircher is a big advocate for the repair and upgrade of existing steel windows, and he is not alone. “Our typical customer is buying an old house because they love it,” he says. “They also know that it is going to have quirks, so they’ll live with a problem – be it plumbing or roofing or plaster – until they find the right solution.” The question then with existing steel windows is how to deal with some of those quirks.

If a steel window needs a lot of work, one approach may be to remove it for a complete overhaul. “It depends upon the installation,” says Seekircher. “Where windows are set into a wood opening, and there is maybe a timber or wood-frame jamb – even with masonry – they are usually just secured by wood screws, which you can undo and then pop the frame out.” But it is not always so simple, as when the window is installed right into the brick or masonry. “Sometimes there is a flange in the masonry,” he says, “and then, after all the brickwork was done, they attached the window to the flange, which makes it kind of hard to get the window out.” Sometimes the flanges are permanently attached, which makes removal altogether impossible. “Installations can be almost as varied as the original contractor,” Seekircher explains.

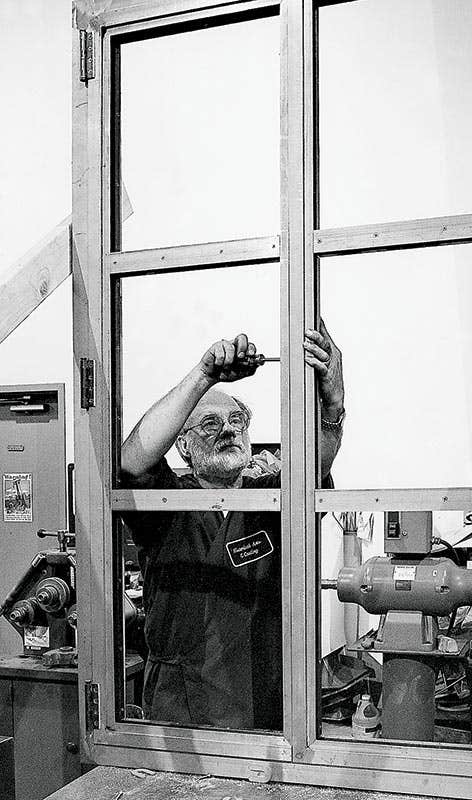

If that’s the case, then it’s time for another approach. “What we do is mark everything and then take the sashes off the hinges so we can do the majority of the work in the shop,” Seekircher says. “It just saves a lot of time and travel.” Seekircher notes that he has customers as far away as Louisiana who ship him windows for restoration. In fact, he says an increasingly common scenario in the Northeast is the house undergoing a major, comprehensive restoration during which the contractor removes the steel windows. “The contractor repairs the woodwork or whatever needs doing and then, after we have overhauled the windows in our shop, we deliver them and they are screwed back in.”

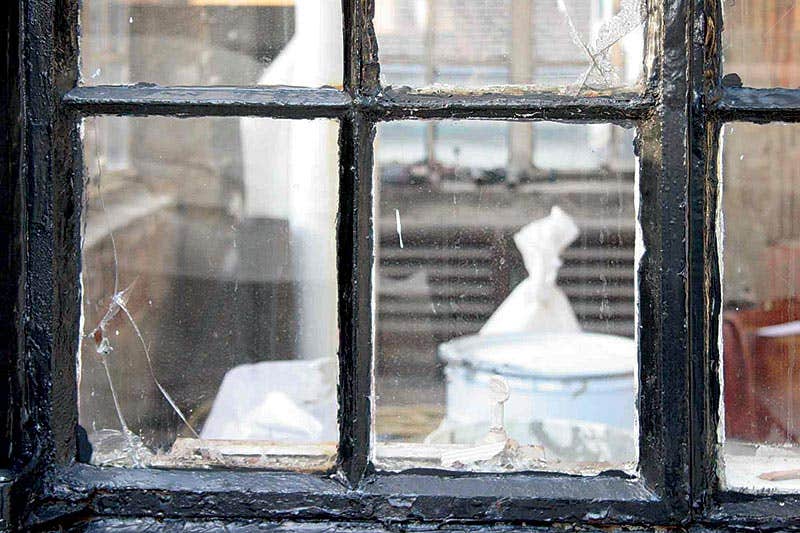

According to Seekircher, unless there has been gross maltreatment of the window – muntins cut away to make room for air conditioners not uncommon – generally, the metal itself is not a problem: “We just did a building at Northwestern University – I’d say it has more than 500 operable windows – and I don’t think we replaced eight feet of steel. However, we are replacing a little more at a private house on Long Island, so it depends upon the environment and how well they have been maintained.” He describes a job in St. Petersburg, Fla., as a gross example. “The house had been neglected and the windows would not open. There were gobs of paint and tons of them were rusted – some an inch from closing.”

The majority of the work he sees is mechanical, because when windows are difficult to operate, lots of other components take a beating. Seekircher describes a textbook job in Colorado: “The sashes were hard to open and close, so, as a direct result, the gears in the operators – which hold many steel windows open or closed – were stripped. When we got the windows to work nice and free, we replaced any broken cranks, locking handles and other parts, and he was in business.” Easy to see why Seekircher is not in the mechanical hardware sales business. “If you don’t solve the problem – which generally is that the window is out of alignment – it is the same as if you hit a pothole with your car and you ask me to just sell you a tire. We want to solve the problem, then replace what is necessary.”

In fact, window misalignment, where the sash has aged or been forced out of position, is another part of the chain of events. “That is how I got started: fixing the operable windows – just getting them to close and improving the seal. Like a chiropractor, we come in and fix that.” This alone, he says, alleviates many thermal complaints. “If you look at the cross-section of the rolled bars that make up the sash and frame, generally they are in the shape of a Z, and the inside face and the outside face lap into each other,” he explains. “So if you get the window closing properly, it will close tight.”

Over and above the mechanical work may be some cosmetics. “Not every window that we work on needs to be stripped and painted,” says Seekircher, “but sometimes folks buying a house or doing a renovation decide to make everything look consistent, so we will do the mechanical work, then we will strip, prime and paint the windows.” Although the majority of residential steel sash are probably front-glazed with putty, similar to a traditional wood sash, architects of the past could also order windows inside putty glazed – that is, with the putty bevel facing the living space. Also, some manufacturers offered models that, instead of putty, used various forms of bars, both on the exterior and interior.

“One of the things I have found a little problematic is where they used glazing bars,” says Seekircher. “Sometimes the bars are solid,” he adds, “and sometimes they’re hollow, and if the latter are on the outside, there is a potential for failure. You’ve got eight corner miters for each pane of glass, plus all the screws that hold the bars, so moisture can eventually get in there.” He adds that he has worked on glazing bars that are still perfect. “If people maintain their houses, [the windows] seem to hold up well – it is all on account of the quality of the original materials.”

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.