Product Reports

A Tall Order: Columns & Capitals

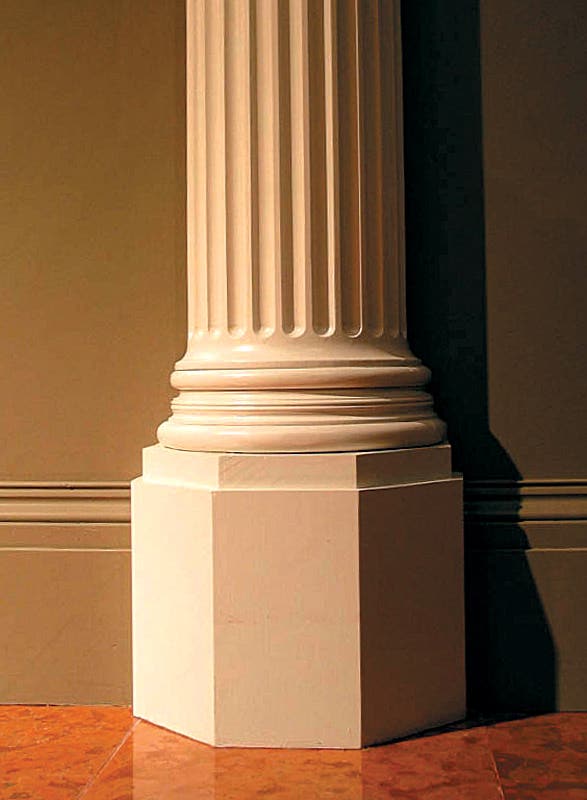

Capitals make their mark as the decorative crowns of columns; bases serve as visual transitions and foundations. However, both these elements must also fulfill important mechanical roles, which means there's more to specifying them than ordering the right architectural order. Whether you need capitals and bases for a new installation or to replace aged or lost units on existing columns, some comments from industry experts can help make sense of the varied materials and casting options in this classic but changing marketplace.

Base-Line Conclusions

After decades of service, the most common historic columns—hollow types composed of wood staves—frequently fall prone to failing bases and column ends, but the reason is not the materials themselves. As Jeffrey Davis of Chadsworth Columns in Wilmington, NC, explains, "Most of the time when clients report deteriorating base moldings, I find that somebody along the line has closed off the ventilation at the top of the column shaft."

Ventilation is critical to release moisture that collects inside the column from condensation on the interior surface, rain infiltration, and even moisture absorption from foundation masonry. When this moisture gets trapped inside the column, problems begin if there is no path out. "Moisture that condenses on the interior surface will run down the inside and sit on the base molding," says Davis, "that is why deterioration appears first at column bases. If we put a non-deteriorating material underneath, but do not fix the problem at the top, moisture is still going to run down, but it is going to sit where the shaft begins and start eating up the bottom of the shaft."

As Davis further explains, in classic column installations there are usually two ways to ventilate at the base: either by incorporating a space under the base or by creating a space between the plinth and the base. The first system is the most common, and manufacturers almost always carry footed bases expressly designed to promote ventilation. The second system comes into play when the base is specified to be a solid material like marble or granite. Adds Davis, "If the client prefers the system where you have the space between the plinth and the base molding, then a lot of times they won't have to have the ventilation at the top because water is going to just run right down and out that space. But our preference—and the preference of all column manufacturers—is that there is ventilation at the bottom and the top of the column."

When columns, capitals and bases are made out of synthetics, such as resin composites or FRP (fiber reinforced polymer such as fiberglass), manufacturers say interior moisture is not a concern, and it is little more than a footnote for another traditional material, cast stone. Says David West of Haddonstone in Pueblo, CO, "Pretty much, there are no interior moisture issues for cast-stone columns and capitals going into vertical façades because, 99 percent of the time, the capital is completely covered by the structure above."

However, in certain instances columns might support a pergola. Says West, "Here some sort of waterproofing—such as flashing—needs to be considered at the top of the capital before any structure goes on top, so a rush of water does not go between the cast-stone capital and the reinforced concrete." Since pergolas are open-roofed structures akin to arbors, the concern is that the tops of the capitals would not otherwise be protected by a beam or other common building feature. "If water gets in and goes through a freeze-thaw cycle, that would be detrimental to the stone." He adds that it is not necessary to cover the whole capital&mdaash; just the top so as to block water from reaching the core.

West says that, in manufacturing columns, his company also includes a water-proofing additive in the cast-stone mixture. "The surface texture of cast stone is like natural limestone, which can appear to be relatively porous. The additive really repels a lot of water that penetrates the material itself." Moisture is not the only issue that has to be considered when specifying column bases; there is construction too. "No matter which company's products a client looks at," says Davis, "they need to consider whether the base is for a fiberglass column or for a wood column; they are two different types of installations." As he explains, with fiberglass columns the base molding and plinth go around the column shaft like a sleeve. For wood columns, the base sits underneath the shaft, so it has to be solid and load-bearing, and it also adds height.

According to Tim Bobo at HB&G Building Products, Inc. in Troy, AL, his company covers the spectrum of stock column materials, but its market leans towards split, non-load bearing, high-density polyurethane for bases. Nonetheless, clients turn to FRP when applications demand another kind of durability. "FRP is not our typical base and capital material," he says, "but we will use it for high-traffic areas, like strip malls, where the bases have to stand up to snow shovels, weed-eaters or skate-boarding kids."

In the case of cast stone, column bases (along with column shafts) may be supplied in vertical half-sections in order to wrap a steel support, or the bases may be one-piece when the haft is one-piece and structural. "In actual fact, though, it is not the cast-stone material that is load-bearing," explains West, "it is the hollow core, which is filled with reinforced concrete, so the load-bearing component is really going to be the center of the column itself." He notes that in these installations, the column requires an isolating medium between the reinforced concrete and the cast stone to accommodate the different coefficients of expansion.

Capital Ideas

Capitals require the same considerations of construction and load-bearing capacity as bases, but here architecture also comes into play. James Garvey at Edon Fiberglass, makers of column covers and pilasters in Horsham, PA, views fiberglass capitals as falling into two categories, a dichotomy that is echoed across other materials and manufacturers. "Most of the capitals and bases that you see outdoors, whether residential or commercial, are Tuscan or Doric," he says, "styles so close in design that most professionals have trouble telling the difference."

After that come capitals and bases that are ornamental, which may be called Corinthian, Temple of the Winds (similar to Corinthian), Roman Ionic or Scamozzi Ionic with volutes (scrolls) angled at 45 degrees. West agrees. "We have about 14 standard column designs that can change capitals," he says, "Corinthian, Ionic, Doric and Tuscan—with which we have tried to assimilate European history while keeping the design as close as possible to being Classically correct."

Says Davis, "For wood columns with wood-like capitals, such as the Tuscans and Dorics, some of the same situations apply as forbases—that is, the capital sits on the shaft, adding height, and may be load-bearing. However, when you switch to a decorative capital, nowadays there are new materials that are also load-bearing." He explains that, in the past, almost all decorative capitals were carved, and then cast in plaster and horsehair. Then each capital would be thoroughly sealed to protect it from the elements and installed around a wood plug in the center that carried any loads down to the column shaft.

"Today," says Davis, "instead of plaster, we can cast with an FRP material that, in and of itself, is load-bearing, so that decorative capitals can sit on top of the column shaft just like wood capitals."

As he explains, such capitals are also hollow in the center, helping to promote ventilation. "Once you have made a mold of the capital, the casting is made by spinning the mold so that the FRP material goes into all the nooks and crannies, producing all the desired detail as well as a hollow center." According to Bobo, "For our ornamental capitals, we use high-density polyurethane, which can make a load-bearing capital up to about 12 in. in diameter. From 14 in. to 30 in. in diameter, they are not load-bearing, but they come with a plug that transfers the load." Besides strength, high-density polyurethane has other advantages for decorative column manufacture. "Polyurethane is a two-part material that, once mixed, expands in volume, so once you load the mold it fills the details," he says.

Capitalizing on History

New capitals typically are ordered either to complete a new column-construction project, or as replacements for some existing, but damaged, capitals. In either situation, clients may face a decision about whether to choose one of the supplier's stock designs or to consider custom-making new molds and castings. Surprisingly, while the financial considerations are noteworthy, the choice does not always turn on money.

"We of course have a standard range of products," says West, "but when we get involved with custom home projects, more often than not the architect specifies his own design of column and, I would say, on 50 percent of the jobs we are actually producing custom columns for that particular environment." West says the drivers vary. "Sometimes it is because the proportions or the technical requirements are larger than the standard columns we carry. What we do, in actual fact, is replicate the architect's drawings; we have our own studio, so we can carve any detail into the capital. We do everything in-house."

To be sure, the need to replicate historic details for a building often leads to making new molds, but sometimes it is a matter of economics. Says Davis, "Quite often we have a client who has 16 columns around their house, but only one capital that is bad; they don't want to replace all 16 capitals, so they will send us the one to replicate, which we have done many times." In fact, Davis says he does a regular business in replicating capitals from manufacturers that were once stock items. "A lot of molds were lost when some of the old-line manufacturers changed hands in recent years," he says. "They often had unique or elongated designs that I can always recognize because there is nobody in the industry making them today."

Garvey sketches a likely reproduction mold scenario. "If an architect or contractor called me about duplicating a historic capital my first question would be, what is the existing material? For example, I often see beautiful capitals in New York City, but they are cast iron, some are corroded, and they are all too big and heavy to remove and mail for use as models." However, Garvey has had clients send 100-year-old samples of wood or sheet metal, such as a tinsmith made, which they can then use as a model to execute shop drawings for design approval. "Once all dimensions are accurate and approved, then we will make a pattern—the physical, positive shape—and from that we make the mold that is used to replicate the parts."

Often, sending a physical capital is impossible, so Garvey's company must rely on old drawings or photographs to execute shop drawings. "In this day and age, most contractors have digital cameras, so in the same day I get a phone call, I can ask the GC 'Can you take some pictures, and if you don't have dimensions, just hold a tape measure up to the capital in the photo.' so we can read it." Says Garvey, "That way, we can at least get a price over to the contractor to see if we are all in the same ballpark."

Whether to go stock or custom inevitably is a case-by-case decision, based upon what is available and how the project pencils out. As Davis says, "I am looking at a once-stock capital now, a rather large Scamozzi that is for a home in Arkansas, but now that those molds are gone you have to make a new mold." Like many column manufacturers, he has no problem re-creating anything that the client or architect has, "it just depends upon which direction they want to go."

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.