Product Reports

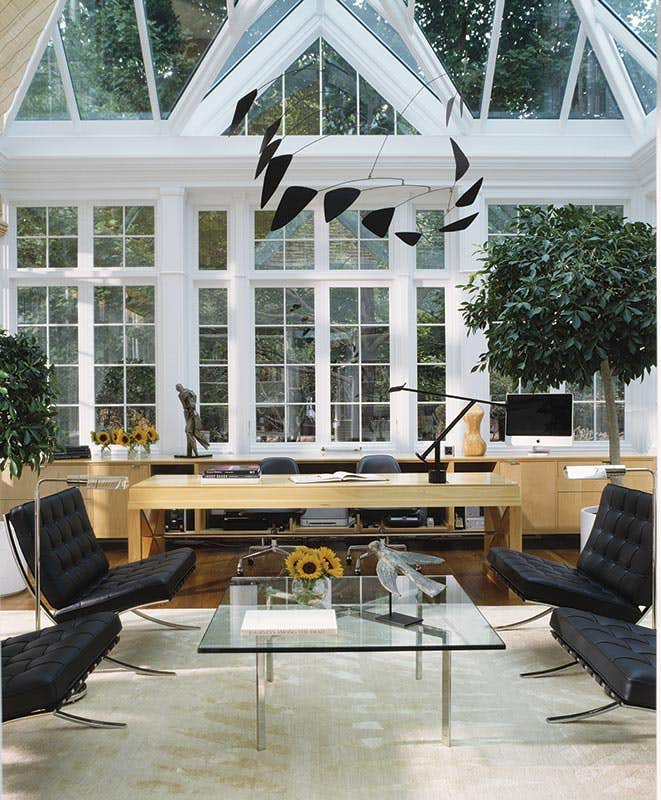

Not Your Grandma’s Greenhouse: Today’s Conservatories

One driver behind the trend is that conservatories are not just for plants anymore. “The majority are used for living spaces,” says Paul Avis of Hampton Conservatories in Huntington Station, NY, “and they can incorporate almost anything, from pianos to pools.” Amy Magner of Oak Leaf Conservatories in Atlanta, GA, and York, England, agrees, and notes that uses vary widely with the client and homeowner. “We see a lot of conservatories chosen to expand a kitchen, as well as adjoin a living room or become a new family room,” she says, adding that sometimes free-standing conservatories are commissioned as outdoor reading rooms or cabanas for pools.

Magner also notes that there is always the purpose that would never have occurred to her company. “We had a client who used one of his two conservatories as a turtle terrarium,” she says.

Creative as this may seem, in reality Americans have only recently begun to think outside of the glass box. As Avis explains, “Conservatories have a long history in England, going back well before the cast-iron innovations of the Victorian era. In fact, prior to the recent recession, UK manufacturers reported producing around 200,000 conservatories a year.” He adds that “The romance of conservatories is the association with Europe.” What’s more, when you step back and consider conservatories as assorted components that can be assembled in different ways, the applications quickly expand. For example, Jim Potrzeba of Glass House, LLC in Pomfret Center, CT, says that while his business is predominantly conservatories, “We also think of ourselves as multi-slope glass suppliers.” Indeed, Glass House has made a specialty of skylights, lanterns and other glazed-roof structures that are, in effect, miniature or wall-less versions of conservatories. “It’s our little niche,” he says.

Not Your Grandma’s Greenhouse

It goes without saying that conservatories are overwhelmingly glass, but beyond this, what makes them up – or more precisely, holds them up? After origins in wood and stone, cast iron lifted the conservatory to new heights in the mid-19th century, and today’s manufacturers still work in the modern equivalents of these materials. Potrzeba says his company concentrates on two types: timber frame and aluminum. “Our timber frames are typically mahogany but, if specified by the architect, we also do other species such as fir or one of the South American mahogany relatives.” As ever, the choice of material depends upon the project. “Our timber frames allow for the tightest joints of the two systems, where that is a concern on a project; aluminum however, can be more cost-effective and may be the choice for meeting fire codes in places such as New York City.” At Oak Leaf, which specializes in hardwood construction, Magner says, “Our main type of wood is a mahogany species, but we have built with other hardwoods.”

“One material can’t offer everything,” observes Avis. Therefore his company works in a range of materials to be flexible for different projects. “Aluminum might be good for the crisp lines of a modern-style building,” he says, “while timber, which allows us to produce almost any detail, can match, say, the deep moldings of a Georgian-style house.” He adds that some clients like wood for its looks, while others concerned about maintenance will prefer metal or aluminum clad in uPVC. At Renaissance Conservatories in Leola, PA, Jason Sawyer says they too use multiple materials. “We build with a combination of premium hardwoods, structural steel, engineered lumber and the highest grade of insulated glass,” he says, “and milling equipment allows us to create ornamental components for any new project, or duplicate moldings in a home over a century old.”

“If you understand how conservatories were built and used in the past, it can open up ideas for a new project.”

Alan Stein at Tanglewood Conservatories in Denton, MD, takes an equally broad view. In his market, he says, “A certain portion is wood conservatories, a certain portion is aluminum and another is for steel.” What, then, drives the choice of one material over another? Says Stein, “If you’re going to paint the structure, then you want a material, such as wood, that takes paint well and maintains well.” Stein says the use also comes into play. For example, he sees a lot of people adding conservatories to living rooms where they may want to match, say, the oak paneling in a living room to oak in the conservatory. “We just did a knotty pine conservatory for clients who had this wood elsewhere in the house.”

Adaptable Expansions

Given that conservatories are among the earliest prefabricated structures with form-follows-function origins, one might assume that they only come in stock styles or kit packages, but nothing could be farther from reality. As Stein explains, “We’re not about reproducing the past or just putting out a product: we’re about creating distinctly new designs according to the needs of each commission.” Magner too says, “Everything we do is custom, every conservatory is unique.” According to Avis, “We don’t have modular systems; it’s all custom-design that is consistent with the property.” However, he says that in his market, that does not necessarily mean recasting building styles or features. “Our clients tend to want something different, something specific to the property, just as a glass building is itself something different.”

Since a conservatory attached to a period house is, in effect, an addition, it raises the question of whether “something different” runs the risk of making a left turn with the existing architecture. As it turns out, such departures from tradition are, in fact, the tradition. As Stein explains, “Historically, a conservatory was often the folly – a fanciful, eye-catching structure – to a formal house.” While some of the earliest conservatories in the pre-industrial era started with Classical designs, emulating the stylistic details of Georgian houses, as the Industrial Revolution took off, things changed. “Designers, such as Joseph Paxton of Crystal Palace fame, started to manipulate new, modern materials of cast iron and steel, and in doing so they created a new, distinctly different building type – a glass bubble if you will. This led conservatories to be architecturally different from the house – an aesthetic that went along with their relaxed nature. This is not merely a historical footnote but a practical guideline for conservatories today. “If you understand how conservatories were built and used in the past,” says Stein, “it can open up ideas for a new project.”

Indeed, all companies interviewed for this article report that the design process begins with a client or architect bringing them an idea, then collaborating with the manufacturer to come up with something that, ultimately, is unique. “In most cases, a client seeks us to take the project from start to finish,” says Avis. “Where an architect is involved, they may have a concept but rarely more – especially when architects already have so many other responsibilities.” As Potrzeba puts it, “There is no typical project. Though we have some standard details, such as for lantern skylights with hipped ends, generally an architect has an idea and from there we work with him or her.” Magner notes that what she sees from architects and designers varies widely, from highly detailed drawings to merely a conceptual sketch.

Like most companies, Oak Leaf will create shop drawings with particular attention to the connections to the house and sections through the building. If an architect wants to include, say, specific molded edges to coordinate with what’s in the house, Magner’s company can incorporate them. Sawyer says, “Our designers sometimes use 3-D design software that allows the architect to plug our system into the new or existing conditions of the building.”

Suppose a client shows up with an old photo and asks, “Can you make this?” In such cases Stein says, “You cannot literally lift from the past. Compared to today, the scale of conservatories is different, the materials are different, and construction methods are different.” However, the process of adapting a period concept to contemporary needs is what excites Stein and his design staff and fuels their passion for the business.

Moreover, there is more to the design of a conservatory than the aesthetics. As Avis points out, “The biggest concern for many U.S. architects is heat build-up – a perception reinforced, rightly or wrongly, by how well conservatories from the ‘early days’ have stood up, and orientation can influence heat build-up and glare.” He notes too that it’s not just about mitigating negatives. “A glass building’s heat gain can be an advantage in the winter snow when you can walk around in your shirtsleeves while the rest of the property is comparatively cold.”

Another critical issue in planning for a conservatory is not the structure itself, but its mechanical systems and how they will interact with the design. “The nature of a conservatory is, of course, that it’s more glass than wall,” says Stein, “so there are no stud spaces, for example, to carry or conceal supply and return lines for heating or cooling – even lighting conduits.” Stein says that planning for mechanical systems should be part and parcel of the conservatory design process from the very beginning – not an afterthought. For example, his company will “get involved at the conceptual stage of the conservatory” and then defer to specialists for the rest of the planning.

“The key to designing a conservatory is to treat it as a living structure,” says Avis. “The different materials – glass, wood, metal and uPVC – all have different coefficients of expansion, so they all move at different rates.” He says the paramount considerations in designing a conservatory are glass specification, ventilation, and shading and controlling heat gain, heat loss and glare. “You need to look at what side of the house the conservatory will be on, and whether there is shade – or water – nearby. You can’t just rely on glass specifications to control the climate. It is a combination of glass specifications, heating, cooling, natural ventilation and shading that make for a comfortable environment.”

On the Glass Cutting Edge

Glass, of course, is the essence of a conservatory, and here the almost monthly advances in products continue to change the conservatory paradigm. “It’s a lot different than the early days when conservatories were simply places for plants,” says Potrzeba, “Now a client can opt for glass with a rating of R5 to even R10; also there are systems to control the heat swings much better than in the past.” He sees a future where conservatories will even chip in towards energy costs. “There are already rumblings of photovoltaic systems for commercial greenhouses,” he notes, “with electricity-producing cells on one face of the glass.”

Says Sawyer, “Advancements in insulated glazing allow our company to build glass-roof conservatories with privacy glass that turns immediately opaque. It is an expensive option compared to standard shades, but an alternative for urban areas.” He adds that his company has also worked with laminated glass to manufacture curved-glass domes, “but curved insulated glass can be very expensive.” Avis too points out that with new glass types you have to balance what’s possible with what’s practical. “As with some innovations in ‘green building,’ there’s just so much you can take on economically.” He notes that since many conservatory projects are traditional in design, the non-traditional appearance of some high-tech glass products needs to be carefully considered as well.

Comfort is optional but impact-resistant glass is increasingly mandatory in weather-prone areas. “As we prepare for more storms like Hurricane Sandy,” says Potrzeba, “we stay current with storm-glass requirements.” Further evidence, as if any is needed, that as time goes on there is ever more one can do with conservatories.

Gordon Bock, co-author of The Vintage House (www.vintagehousebook.com), is an in-demand speaker for courses, seminars, and keynote addresses through www.gordonbock.com.