Features

2012 Clem Labine Award Goes to Jean Carroon

By Martha McDonald

Go to any meeting or convention remotely related to architecture and you will likely find Jean Carroon promoting stewardship of our existing buildings and demonstrating how it all relates to the environment. She has delivered this message as often as possible to as many audiences as possible. Carroon has lectured on preservation, sustainable design and related environmental issues in such places as the Traditional Building Conference, the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, and New York’s Municipal Art Society, and she has participated in panels for the General Services Administration, AIA Livable Communities, the Association for Preservation Technology, and the Green Building Alliance. She is also a member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Sustainability Coalition and the current chair of the AIA’s Historic Resource Committee.

Jean Carroon, FAIA, LEED, a principal with the design firm Goody Clancy of Boston, MA, shies away from the limelight, but she is adamant that her message about caring for existing buildings should be environmentalism’s highest priority. “Responsible stewardship and maintenance, taking care of what we already have, is the most important step towards sustainability. I just started formulating my message that way the last couple of years, but that is the reason that I went into preservation in the first place,” she says.

Carroon also found time to write a book – although she admits it was a painful process. Sustainable Preservation: Greening Existing Buildings was published in 2010 by John Wiley & Sons. In it, she presents information showing that buildings account for 40% of our energy use and carbon dioxide emissions, and provides data on how to adapt these buildings for more efficient use. She points out that it is not only significant historic buildings that should be saved, but also shopping malls and more contemporary buildings. Saving any building avoids the environmental impacts and raw material consumption inherent in new construction. Fifty case histories provide specific information and how-to data.

She is pleasantly surprised to see that the book continues to be successful. “I thought it would become dated,” Carroon notes, “but it has been the opposite. The information seems to be lasting.” Carroon has also written for various publications, including Traditional Building.

It is all of these contributions beyond her day-to-day job that brought Jean Carroon’s name to the top of the list when the editors selected the recipient of the fourth annual Clem Labine Award. Founded in 2009, the award recognizes a person who has made a long-term commitment to creating a more humane environment. Named after Clem Labine, founder of Old House Journal, Traditional Building and Period Homes magazines, the award has previously honored Alvin Holm, AIA, of Alvin Holm Architects; Steven W. Semes, architect, author and professor of architecture at Notre Dame School of Architecture; and Raymond L. Gindroz, FAIA, co-founder of Urban Design Associates.

Labine notes that the winner of the award could be an architect, artist, craftsperson, community leader or some other professional, as long as that person is making significant contributions outside of his or her job, with vocational and avocational goals that are intertwined. He often describes it as “a life with a purpose.”

Carroon is definitely on a purposeful path. She graduated from high school in Jackson, MS, and went to the University of Oregon. After earning a Bachelor of Arts, she attended a Career Discovery Program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, which awakened her interest in architecture and design. Carroon earned a Master of Arts in architecture at the University of Oregon in 1986, and then she and her husband moved to Boston. “There was no work in the Northwest,” she says, “and Boston was booming. We arrived on a Tuesday and my husband had a job on Friday.”

She got a job at Shepley Bulfinch and then moved to Ann Beha Architects in 1987. She stayed there until 1994, when she started her own firm, Jean Carroon Architects. “My degree wasn’t in preservation, but my interest always was,” Carroon explains. “Ann Beha was doing a lot of preservation and I got to work on the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall as well as multiple projects at Harvard University. When I went on my own, I had a strong reputation in historic preservation.”

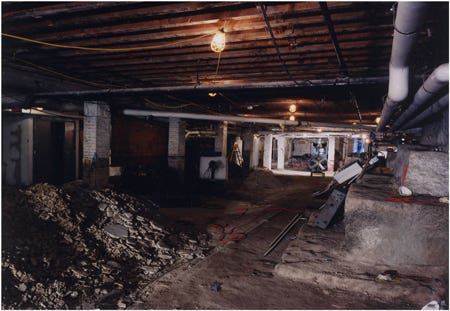

Then in 2000, she took her staff of 10 and joined Goody Clancy. “Goody Clancy had been awarded the expansion and partial renovation of Trinity Church [1877, H.H. Richardson] and we had the opportunity to be involved,” Carroon notes. “On January 1, 2000, I started working with Trinity Church and we are still working with them today.” One of the upgrades made to this historic building was the addition of usable space in the undercroft, built around the piers supporting the church. The project also incorporates ground-source heat pumps to improve energy efficiency and to eliminate the installation of visibly intrusive equipment.

“Trinity Church was a career-maker,” she says, “but we have many other wonderful projects.” Recently completed work includes the LEED Gold restoration of the John W. McCormack Post Office and Courthouse in Boston for the General Services Administration, two renovations of historic residential halls at the University of Michigan and a LEED Platinum student welcome center at Champlain College in Burlington, VT, which restored and added to an antebellum home.

One current renovation is the Romanesque Revival U.S. Post Office and Courthouse in Brooklyn, NY. “We are in the third year of a three-year terra-cotta renewal there,” she notes. “The new terra-cotta [done by Boston Valley Terra Cotta] is really magnificent.”

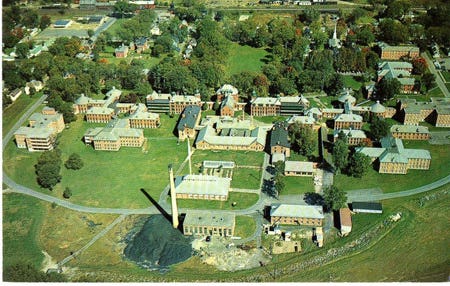

Work is just beginning on the Waterbury State Office Complex, a 700,000-sq.ft. former psychiatric hospital in Waterbury, VT, that dates from 1890. Goody Clancy, in partnership with the Vermont firm of Freeman French Freeman, is developing renewal strategies for the site, which was damaged in the 2011 floods caused by Hurricane Irene. The most historic buildings on the campus will be restored and protected against future flooding. New office space will use durable local materials with on-site generation of low carbon energy and overall changes to the site will improve flood mitigation, by among other things, demolishing some of the existing buildings.

Although Carroon believes passionately in the reuse of buildings to decrease the environmental impacts of new material consumption, she is pragmatic about the definition of green, recognizing that buildings must work economically and socially to be sustainable. In February 2002, she was one of the first people to become LEED accredited. “I was quite early,” she notes. “We were interviewing for the McCormack Courthouse project and the GSA (General Services Administration) had mandated that all projects had to be LEED. It was a real turning point in the marketplace and very exciting.”

Preservation vs. Sustainability

Do preservation and sustainability work together, or do they conflict? “This has been asked as long as I have been working on sustainability,” Carroon says. “I don’t believe it is a conflict. I think of it as an energetic conversation about what stewardship really needs. I do believe that the preservation community continues to be inappropriately focusing on freezing buildings in the past. And it is often a past that never existed.”

To illustrate this point, she cites the example of the University of Virginia. “There was quite a reaction when one of the pavilions was restored to its Thomas Jefferson appearance, which was not white. It was a taupe color. People thought it should be white, because it’s been that way for decades. It is interesting how often our observations of the past are not fact based.

“There are a lot of historic commissions that are most concerned with how something looks, and focus on whether new technologies, such as solar panels, are visible, for example. I think we should be trying to safeguard the actual historic fabric, doing no harm as opposed to worrying about how they [the buildings] look.”

She adds that it is all about balance between the appearance of the building and sustainability. “The appearance may be part of the economic health of a community. The question is whether having visible solar panels would impede heritage tourism or real estate values,” Carroon explains. “It is always about balance. What are your objectives and goals?”

“I am less worried about individual building alterations than the increased pressure to remove buildings to accommodate density. How do you define density? If our individual living units are getting bigger and bigger, are we building a sustainable future?”

Looking Ahead

“Getting this award has made me think a lot about my goals and my effectiveness,” Carroon muses. “I have been in a quandary since the book came out. What do you do to keep the momentum going? I am not sure I have the answer yet.”

She is concerned about “getting to a broader public about the use and reuse of buildings as a primary form of recycling and maintenance and as a primary form of sustainability,” creating a “tipping point,” and has another book in mind. This one could be shorter and simpler so that it would appeal to a broader audience. “I might even start by blogging, and then developing it into a book.”

On an optimistic note, Carroon sees increased stewardship and sustainable activity occurring on academic campuses. MIT, for example, has a major building evaluation program underway, and is “emphasizing stewardship and maintenance. We are seeing academic institutions focusing more intently on the buildings that they already have and talking about life cycles of hundreds of years. That’s very encouraging.”

She also cites the work being done in the city of Cambridge, MA, to respond to climate change. “How do you mitigate and plan for climate change? I find this really interesting. And it ties in with saving our existing buildings.” This is not dissimilar to the work on the Waterbury Complex in Vermont, which involves large-scale planning as well as the restoration of the 100-year-old historic core. “It is my dream project in this new world,” Carroon says.

Speaking of new worlds, Carroon sees a need for a new economic model. “We need to shift to an economic structure that supports repair and reuse rather than replacement,” she says. “This applies as much to individual elements as to whole buildings. I think a carbon tax could be the heart of this. We need to make new materials less desirable than repair, so that extending service life of any object is the preferred option. We then avoid the substantial environmental and toxicity impacts that every new object has regardless of how ‘green’ it is.”

Carroon cites window replacement as a symbol of our throw-away culture and notes that preservation is one of the few bastions against this wasteful mentality, and adds: “It is a very hot topic because of the widespread belief that new material consumption (i.e. a new window or a new building) is required to substantially reduce operational energy. I believe in a less-is-more approach, using the least new materials possible to achieve the greatest improvement in building performance. We must also remember that dollar for dollar, renovation and repair create more jobs than new construction. There aren’t many groups making these connections.”

And she wants to do all of this without drawing attention to herself. “The next 10 years are a real opportunity for all of us. My biggest challenge is that the people that seem to make the biggest changes often seem very self-centered. I am wondering if there is a way to initiate change and really be a force without being the center of attention.”

Let’s hope that more people are paying attention to her message.