Features

The 2011 Clem Labine Award: Ray Gindroz

By Kim A. O'Connell

In the six years since Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast, a torrent of words has been written on how to rebuild after the disaster. Every possibility has been considered: preserve, tear down, build modern, build green. Some of the most civilized and beautifully wrought solutions, however, can be found in Louisiana Speaks: Pattern Book. "As we walk through these streets, or remember the places now gone," the book states, "it is the graceful porches, the windows that go to the floor, the ornamentation on the frame around the door…that tell us where we are – and who we are."

The book, which contains architectural patterns and techniques rooted in Louisiana traditions, was developed by Pittsburgh-based Urban Design Associates (UDA), led by Raymond L. Gindroz, FAIA. Gindroz has devoted his long career to rebuilding and renewing communities in need and fostering an appreciation for traditional design among laypeople and in the academy. For these and other achievements, Gindroz is the winner of the third annual Clem Labine Award.

Founded in 2009, The Clem Labine Award honors a person who has made a long-term commitment to creating public places that foster community, civility and traditional design. The award is named for longtime publisher, author and traditionalist Clem Labine, who founded this magazine, among others. According to Labine, the winner of the award may be an architect, artist, craftsman, community leader or some other professional, as long as that person is leading "a life with a purpose" and has vocational and avocational lives that are intertwined. The first two recipients were Alvin Holm, AIA, and Steven W. Semes. In naming Gindroz to this illustrious roster, Labine hailed his work as an urban planner, architect and philanthropist.

Gindroz began his architecture career as a student at Carnegie Mellon University, where he earned both a bachelor of architecture degree and a master of architecture in urban design, each with honors. In 1964, while still in graduate school, Gindroz was invited by David Lewis to co-found Urban Design Associates. Lewis, who established the urban design program at Carnegie Mellon, was exiled from South Africa in 1946 for his anti-apartheid activism. In the 47 years since its founding, UDA has received more than 100 awards for its work in building and rebuilding neighborhoods, including national AIA Honor Awards, Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Charter Awards and Palladio Awards.

According to Gindroz, UDA's goal is to design not just buildings, but communities, and to empower citizens through pattern books, charrettes and other outreach programs. Gindroz has led urban design projects in many U.S. cities including Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Louisville, Norfolk, Richmond and New Orleans, as well as others in France, Scotland and England. The firm has developed urban design and architectural designs for more than 25 Hope VI projects since 1994. This federal program replaced some of the nation's most distressed public housing with mixed-income neighborhoods. UDA's designs in many cities have been built as new neighborhoods, connected to adjacent neighborhoods and assimilated into their communities instead of standing apart.

"Early in our career, after trying to design neighborhoods with some of our Modernist vocabularies," says Gindroz, "we quickly learned that people in communities that had character were very concerned about keeping that character. We also learned that the design of dwellings and neighborhoods can play a very positive role in the social sustainability of a neighborhood. For example, when the character of a barracks-style public housing project was transformed into a typical neighborhood through the addition of porches and traditional elements, children began doing better in school. According to their teachers, this was because of an improved self-image. They were no longer kids from the project, but rather from a neighborhood."

Among other achievements, Gindroz has taught at his alma mater, Carnegie Mellon, as well as at Yale's Graduate School of Architecture, and in a series of short courses at McGill University, Hampton University and the Prince's Foundation for the Built Environment in London, where he is a senior fellow. He is a past chair of the AIA's National Committee on Design, the CNU and the Seaside Institute, and serves on the board of several foundations. Gindroz' drawings and plans have been featured in more than a dozen notable exhibitions and he has written several books, including The Place of Dwelling, published by the Prince's Foundation. He was the principal author, along with others at UDA, of The Architectural Pattern Book: A Tool for Building Great Neighborhoods and The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (published by W. W. Norton & Company).

Patterns for Living

Gindroz remembers a time in the mid-1980s when he and a photographer visited a traditional development in Richmond that the firm had designed. As they walked around taking pictures, a resident walked up to them and asked what they were doing. When Gindroz explained his role as the architect and talked about the development's traditional design principles, the resident brought the discussion down to the most fundamental terms. "This is a neighborhood. Can't you see that?" the man said, with full understanding. "There are families here."

Gindroz quickly noticed that whenever the firm went out into neighborhoods, talking with the people who actually lived in them, they responded most readily to traditional concepts. One of the firm's earliest commissions, for example, was to develop historic district guidelines for the city of York, PA, which at that point had the largest historic neighborhood on the National Register of Historic Places. "We carefully analyzed the block of Victorian-era houses," says Gindroz. "We were astonished at how simple they were from a building standpoint – how correct they were. They were always extremely attractive, whatever the mix of styles and building types. The whole was very harmonious."

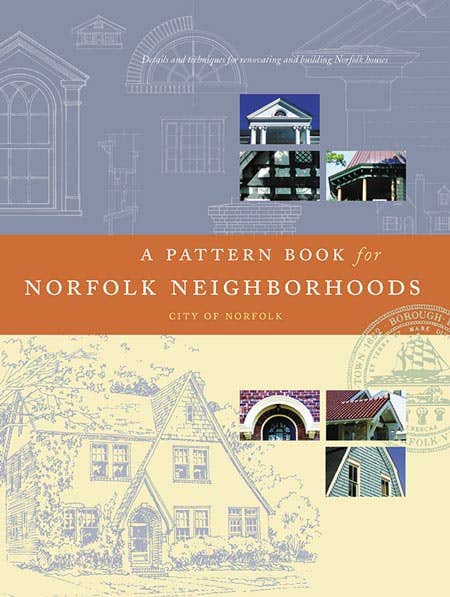

Putting those concepts into architectural pattern books for modern times was a natural progression for the firm and has become an important part of its identity. Pattern books date to ancient Roman times and were in continual use in the U.S. through the postwar period. Yet they had fallen out of favor with the rise of Modernist, isolating buildings and sprawl-inducing development. "We began writing these guidelines and gradually called what we were doing 'pattern books,'" says Gindroz. "We did more and more research into how they were done in the past and thought about how we could do them in the 21st century. The breakthrough came with Celebration [the New Urbanist development in Florida]. We started out doing design guidelines, but it turned into a full pattern book. Design guidelines are usually a source of warfare between developers and architects. Pattern books are non-confrontational. The more we studied neighborhoods, we realized that by working with the traditional architectural vocabulary you could introduce new things in new ways that were comfortable for people."

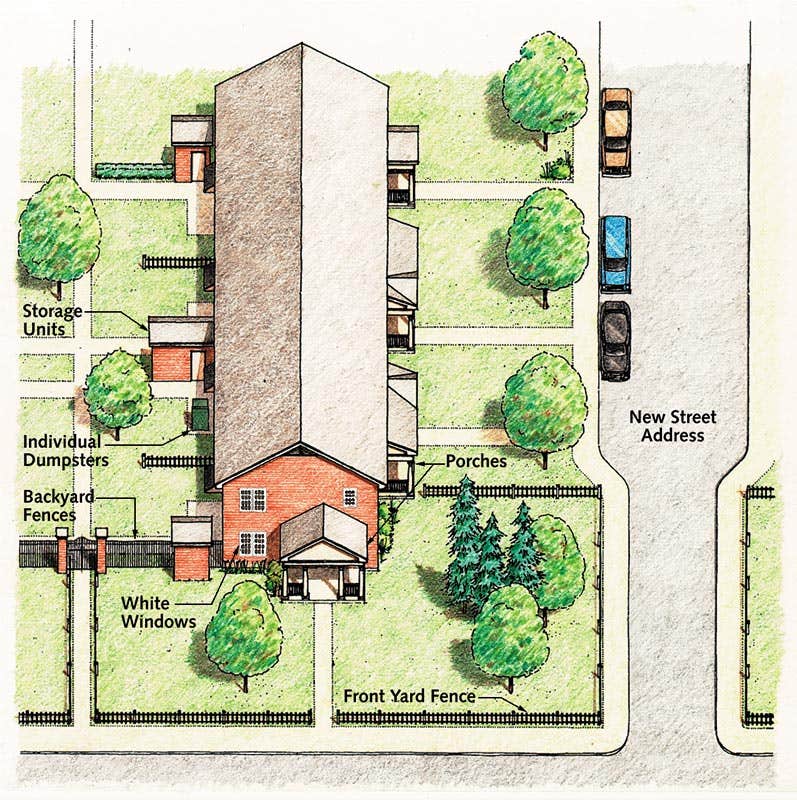

With a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Surdna Foundation and the Fannie Mae Foundation, UDA developed A Pattern Book for Neighborly Houses, a joint project for Habitat for Humanity and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. Clearly written and beautifully illustrated, the book could be read and understood by building professionals and laypeople alike. After an overview that includes the definition of a so-called "neighborly house" – one that is set back from the street and aligned with other houses, with a front yard or possibly a front porch and well-placed parking – the pattern book offers an instructive look at neighborhood patterns, housing patterns and housing types. The overview of American architectural styles provides dimensions and details, and a guide to sustainable design is perfectly compatible with the traditional concepts illustrated elsewhere in the book.

The Louisiana Speaks: Pattern Book, which was prepared for the foundation-funded Center for Planning Excellence in Baton Rouge, was the result of a series of workshops and charrettes in which residents identified what was essential to them after hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Participants were almost universally worried and angry that so much of the state's traditional and vernacular character had been lost, and they hoped to restore and rebuild in ways that preserved their history and culture.

To this end, the pattern book outlines residential building types and architectural styles that are consistent with Louisiana traditions. This work continued when the firm was asked by Providence Homes and Enterprise Homes to lead the design team for the rebuilding of the Lafitte Public Housing Project in New Orleans after Katrina. Now called Faubourg Lafitte, this new, traditional New Orleans neighborhood is being built in phases, with the first 150 units occupied. By applying the traditional urban and architectural patterns of the adjacent Treme neighborhood, its new houses and apartments create a seamless extension of the traditional city.

The pattern book, which was given away at local Lowe's home improvement stores, has already gone through two printings.

Building a Foundation

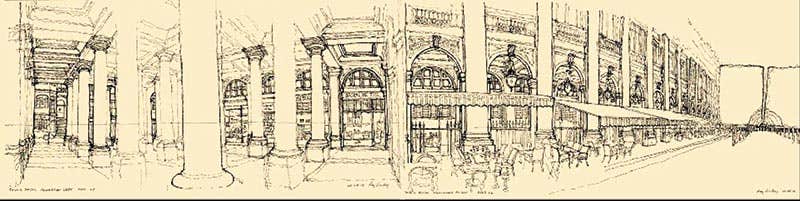

When Gindroz is not running a charrette, writing a pattern book or designing a neighborhood, chances are he's drawing. Over the years, Gindroz' evocative ink line drawings of buildings and towns, vaulted ceilings and other Classical details proved to be so popular that people often asked Gindroz if he would sell them, but he was never interested. One day, his wife Marilyn suggested that he could sell them for a good cause, and the Marilyn and Ray Gindroz Foundation was born.

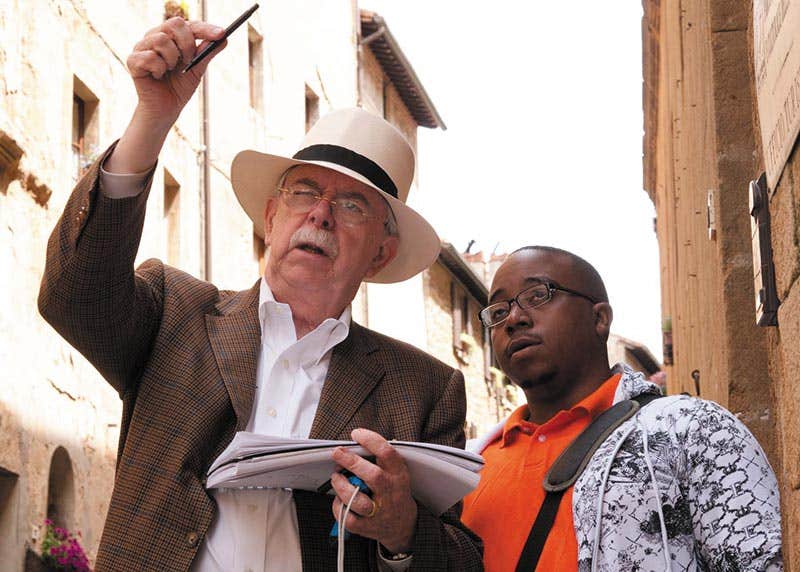

Through the sale of Gindroz' original drawings and printed sketchbooks (available online), as well as contributions, the foundation funds an annual study travel prize for music and architecture students at Carnegie Mellon. It also provides financial, logistical and teaching support for the Hampton University Architecture Department's study abroad program. For the past four years the Gindrozes have worked with faculty members on programs in Italy and France. The students draw and analyze traditional urban spaces and meet with traditional architects, including Pier Carlo Bontempi, Leon Krier, and Ariel Balmassiere, as well as local officials and other architects.

Gindroz says he is honored to receive the Clem Labine Award and is especially pleased that his foundation work played a key role in the jury's selection. "Our foundation is dedicated to promoting ideas about humane urbanism, both through the drawings and the study-abroad programs," he says. "We do believe that exposure to other cultures is a truly a life-changing experience, and we want to provide those experiences for the next generation of architects."