Profiles

Architect Patrick Ahearn On Levittown, New York

Patrick Ahearn, FAIA, grew up in Levittown, New York, a place he recalls fondly and in great detail. Built in the late 1940s, the “mass-produced suburb” was distinct for its curvilinear lanes dotted with 17,456 nearly identical houses. For Ahearn, the place was brimming with lessons that he has carried with him throughout his career.

Designed by architect William Levitt—considered to be the father of modern suburbia—Levittown was built on Long Island’s potato fields and featured Cape Cod-style homes, built between 1946 and 1948, and ranch houses, erected from 1949 until 1951. Although each slab-on-grade house had the same floor plan, there were four variations of the façade; and because each house was placed on its lot in a different pattern, they didn’t line up, which lent some visual interest. “One of the most critical ingredients of Levittown’s success was that it wasn’t based on a grid,” notes Ahearn.

Commonalities included a double-sided brick fireplace flanked by wrought-iron candlestick holders that served the living room and kitchen; a full wall of floor-to-ceiling glass in the living room; built-in bookcases; swing-away blond wood cabinets that could close off the kitchen; radiant heat; a TV under the stair; and an attic set up for the addition of a bathroom and two bedrooms. (All of the houses were designed to expand.) Each exterior featured a slate walkway, a weeping willow tree, and two crabapple trees. Because the houses did indeed expand, their uniformity wasn’t so blatant over time. In fact, there is not a single original house in Levittown today. “There was this notion about how the houses could change that was somewhat preordained based on where the dormers and windows and stairs were located,” explains Ahearn. “It was easy to understand where you would put a bedroom or a bathroom or such.”

Village greens were built at the same time the houses went up, and the fertile soil of the potato fields meant street plantings grew quickly. Within five years, the lanes were lush with tree canopies and grassy islands between the roads and sidewalks. The close proximity of the houses to the greens affected how people lived. “Kids played communally—not on the street but in [adjacent] yards, which were connected to bike paths, which led to the village green, which had a community swimming pool, library, elementary school, and goods and services,” Ahearn explains, noting that many of the principles of New Urbanism were at play in Levittown. “I always walked to school and to the village shopping areas. It really instilled in me some thinking about walkable towns and villages.”

Ahearn picked up on many of the suburb’s subtleties, too. He recalls that telephone poles were sited on the backside of houses to eliminate wires from the streetscape, which had granite curbs and well-designed street lamps. He also remembers the stone and timber guard rails, expansive plantings, and intertwining bike paths that were part of the parkway system around which Levittown was built. “I have all of these great memories of bicycling in the woods and sledding on a hill that was part of the parkway,” he muses.

Not only was Levittown the setting for Ahearn’s boyhood, it was also the subject of his master’s thesis for which he examined the place from an architectural-sociological perspective. The neighborhood’s egalitarian structure is something he appreciated. Each 860-square-foot house cost $7,900 on the GI Bill; buyers put $100 down and paid $60 per month for 20 years. “Everybody was kind of the same—with the same socio-economic conditions,” he notes. “It was a fairly cohesive community. It wasn’t about the haves and have nots.”

Memories of Levittown continue to inform Ahearn’s work, which he describes as “historically motivated.”

Having completed his studies at Syracuse University, the architect moved to Boston, where he worked for two prestigious firms: Benjamin Thompson Associates and The Architects Collaborative. Large commissions included Faneuil Hall Marketplace, three hotel resorts in the Middle East, and a petrochemical complex in Jubail, Saudi Arabia. He simultaneously began converting historic Back Bay row houses into condominiums—work that would become his focus. Upon taking leave from the Architects Collaborative, Ahearn opened his own firm in 1978.

In addition to historical renovations, Ahearn developed a new vision for Newbury Street that included sorely lacking restaurants, cafés, shops, and second-floor living spaces. “I pioneered a lot of the thinking behind what you see on Newbury Street today, particularly as it relates to the cafés and the two first floors idea to help support the economics of building renovations,” he says.

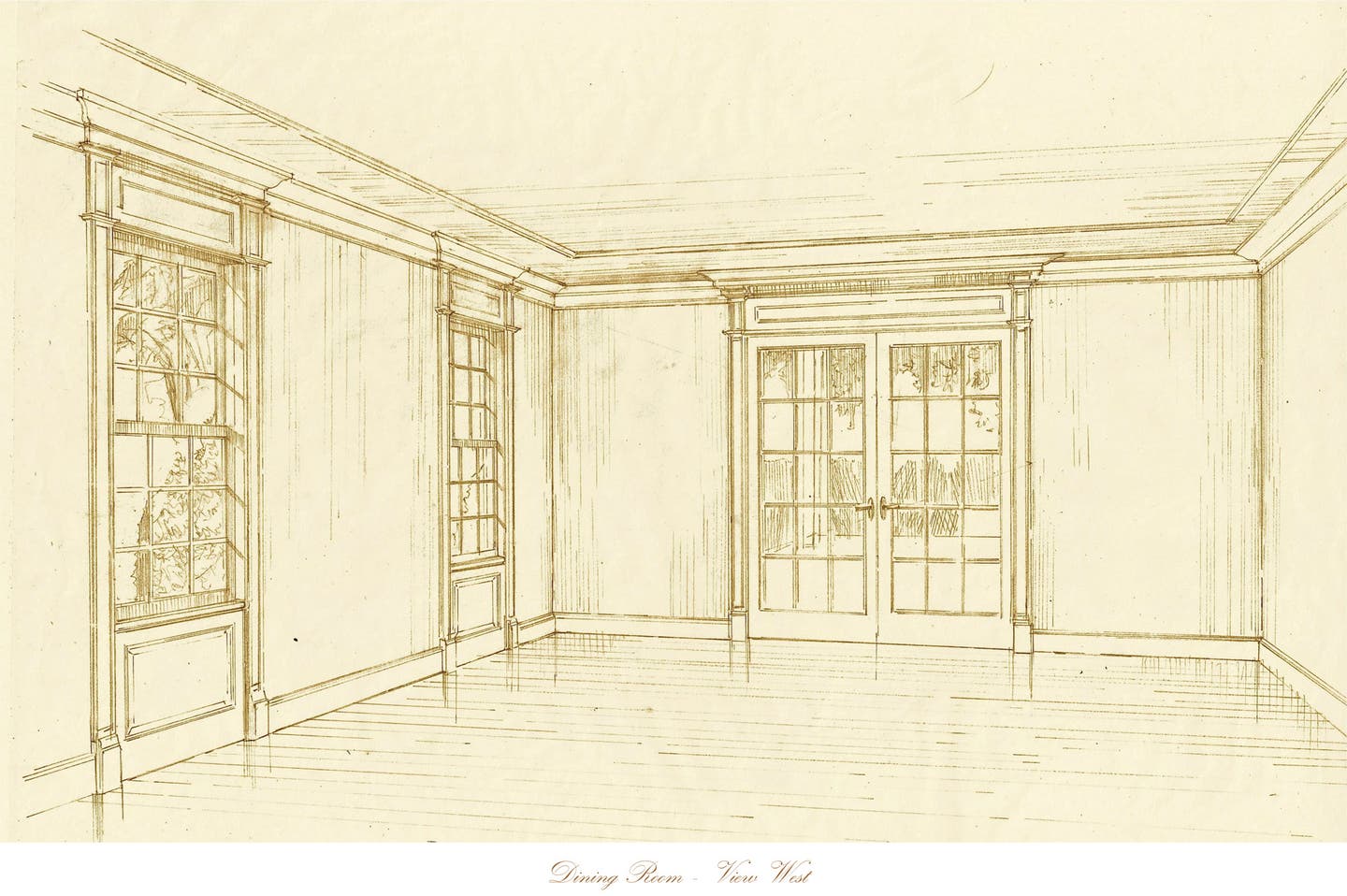

In time, Ahearn purchased property on Martha’s Vineyard, where he began doing a “sketch of the week” for The Vineyard Gazette. Out of those drawings came 26 new commissions. Ultimately, he set up an office in Edgartown Village, where he has practiced for the last 25 years. To his credit are 172 houses and most of the town’s commercial projects, as well as the Boathouse Field Club, the Edgartown Yacht Club renovation, and the revitalization of downtown—façade by façade. “It’s somewhat like my American Flyer train set, only in real life,” he jokes. “I’ve done a whole little village, which is really satisfying.”

Downtown Edgartown demonstrates the architect’s “Greater Good Theory,” which “enhances the quality of life for the overall community while respecting the local character, scale, and imagery”—clearly a tactic with roots in those long ago potato fields. n

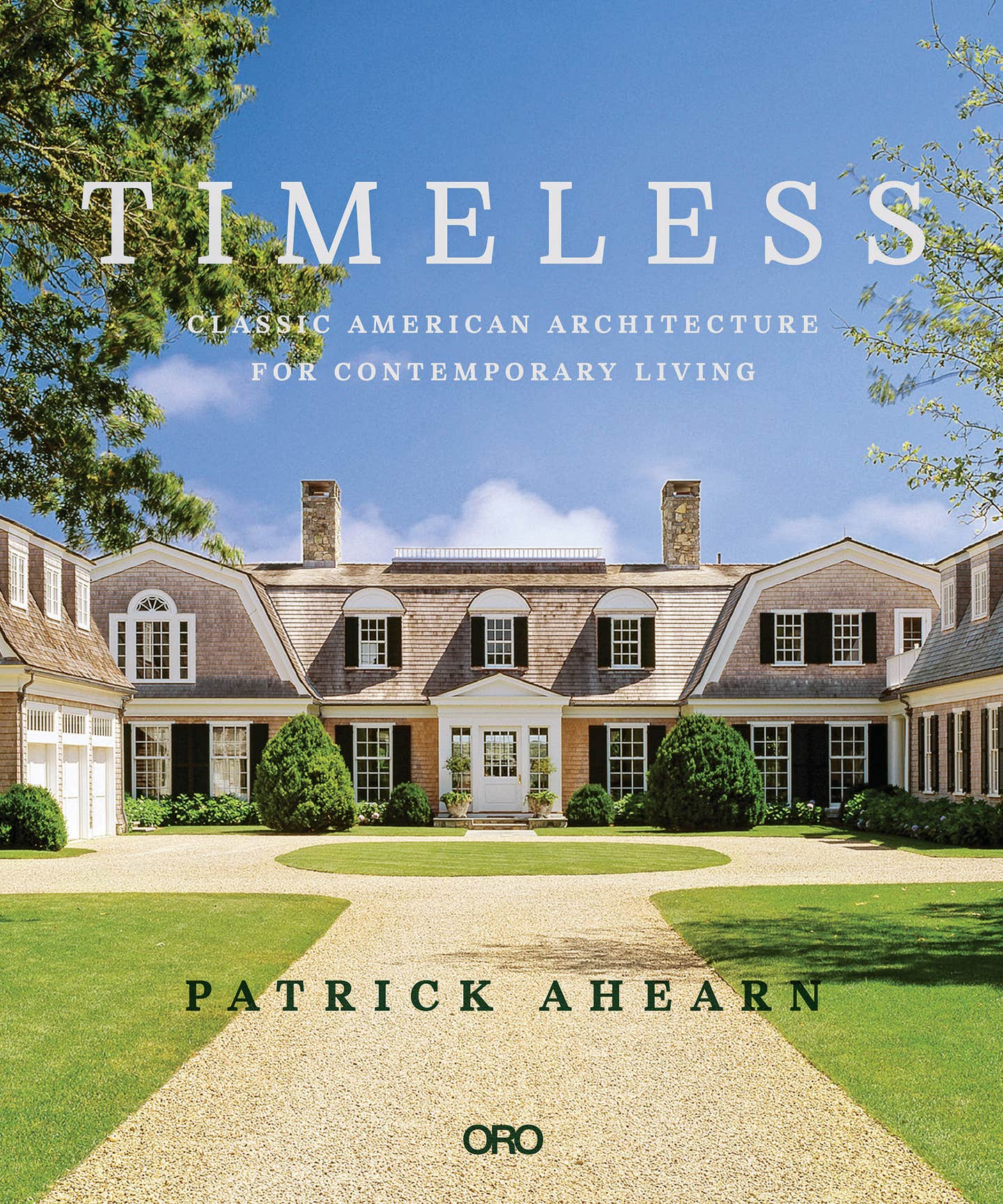

NOTE: Ahearn’s newly released Timeless: Classic American Architecture for Contemporary Living showcases 18 projects that demonstrate his idea that design has the power to improve lives and enhance happiness.