Profiles

The Meaning of Mouldings

Before she was a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, 19th-century writer Edith Wharton coauthored The Decoration of Houses, a rich description of how architecture relates to furnishings and ornamentation. The pioneering book, which takes mouldings and other interior features to lofty heights, has served as a guiding star for designer Leslie-jon Vickory in her work at Hamady Architects, the architectural design firm in Boston and Greenwich, Connecticut.

Moulding, for Vickory, is an essential part of the vocabulary of Classical architecture, with the power to take the mood of a room to a soaring song. “Mouldings are integral to the Classical principle of symmetria,” Vickory says. “They proportion elements within a space and relate the elements to the whole, and vice-versa.”

While the function of moulding is simple—strips crafted from various materials that cover transitions between surfaces or simply for decoration—the device helps to articulate a space and define its character. “It’s more than just covering the joint between the ceiling and wall, or wall and floor,” Vickory says. “It has a rich history and a profound purpose.”

With roots in ancient Classical language, moulding, Vickory says, becomes a distillation of “the Orders in a graceful, accessible, and simplified nature.” For example, even a chair railing, she says, is representative of a column’s pedestal.

Whether a cornice, frieze, architrave (framing around windows and doors), fireplace mantel, or another type, mouldings are part of a visual, coherent language.

In her quest for interiors that don’t grandstand but lean on proper proportions and scale, Vickory —who usually draws by hand—is very much at home at Hamady Architects, a small firm begun by its sole principal, Kahlil Hamady. Here, Vickory, Hamady, and their colleague Mark Jackson immerse themselves in projects imbued with classicism.

“Classical language is the foundation of our work,” Vickory says, “from initial concept and design, its rules and principles are applied throughout our practice.” Among the firm’s many commendations are four Stanford White Awards, one Palladio Award, and two Bulfinch Awards. Staff work symbiotically among themselves and clients, with Vickory at times consciously bringing “a feminine aspect” to interior architecture.

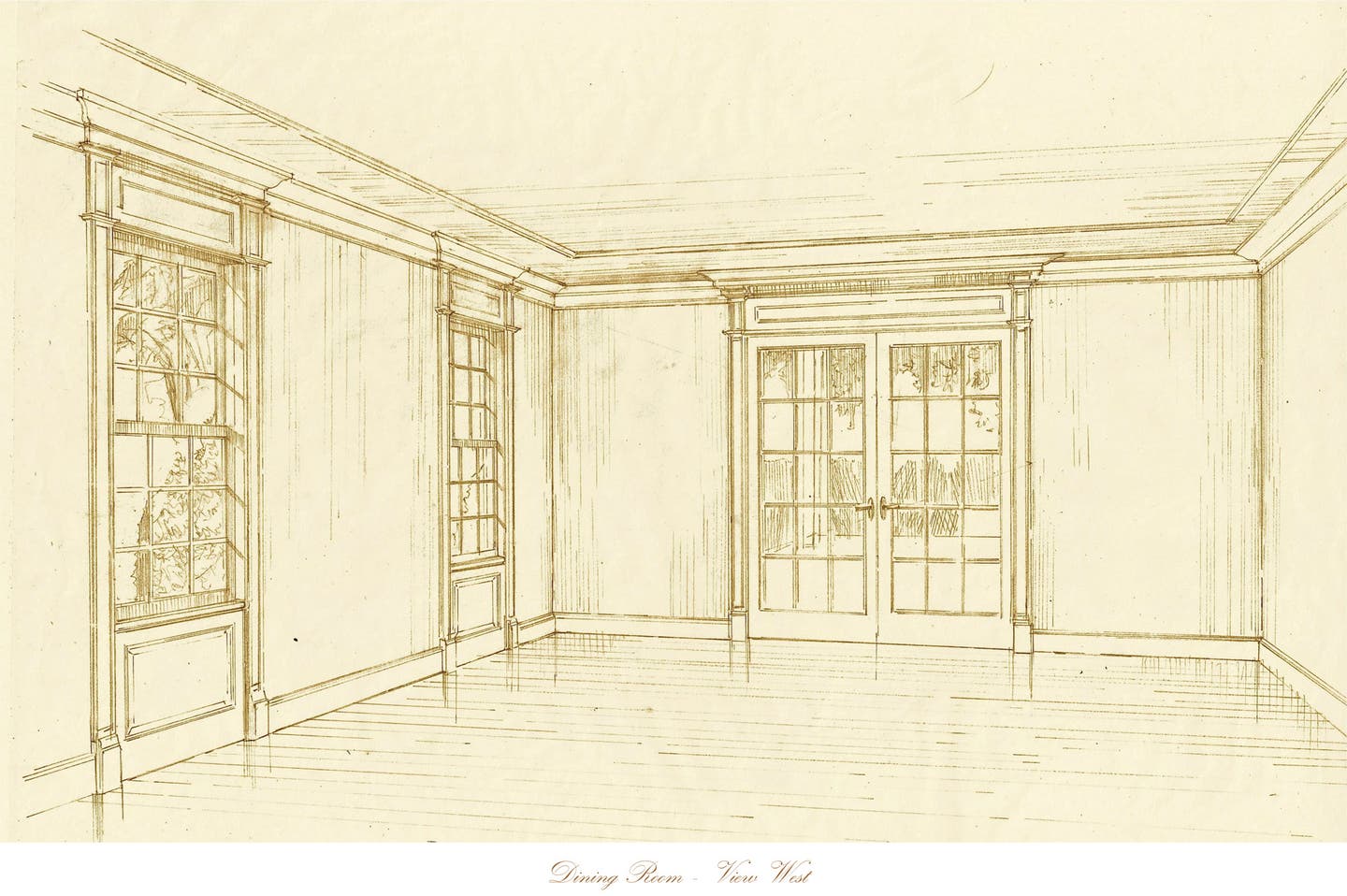

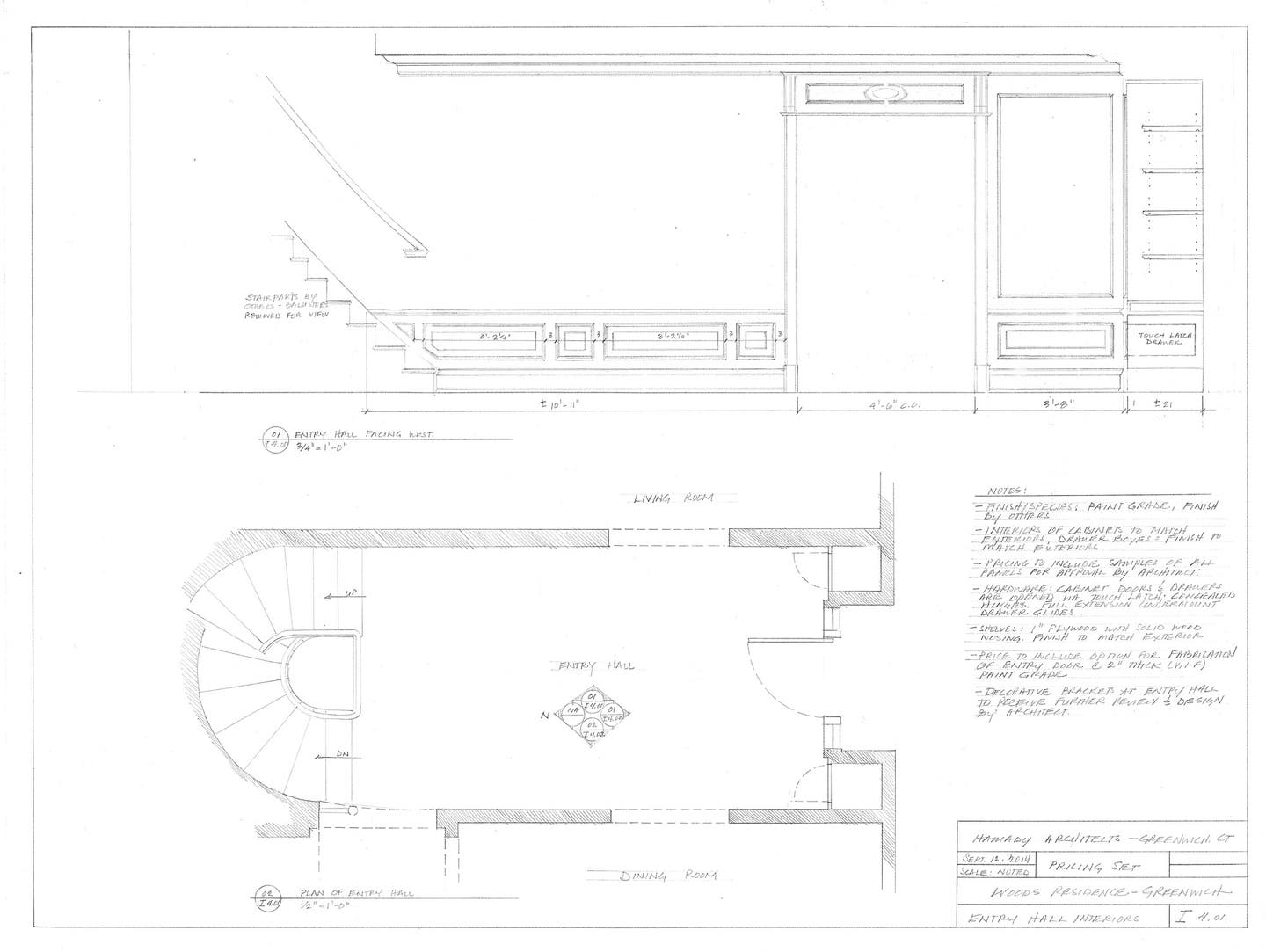

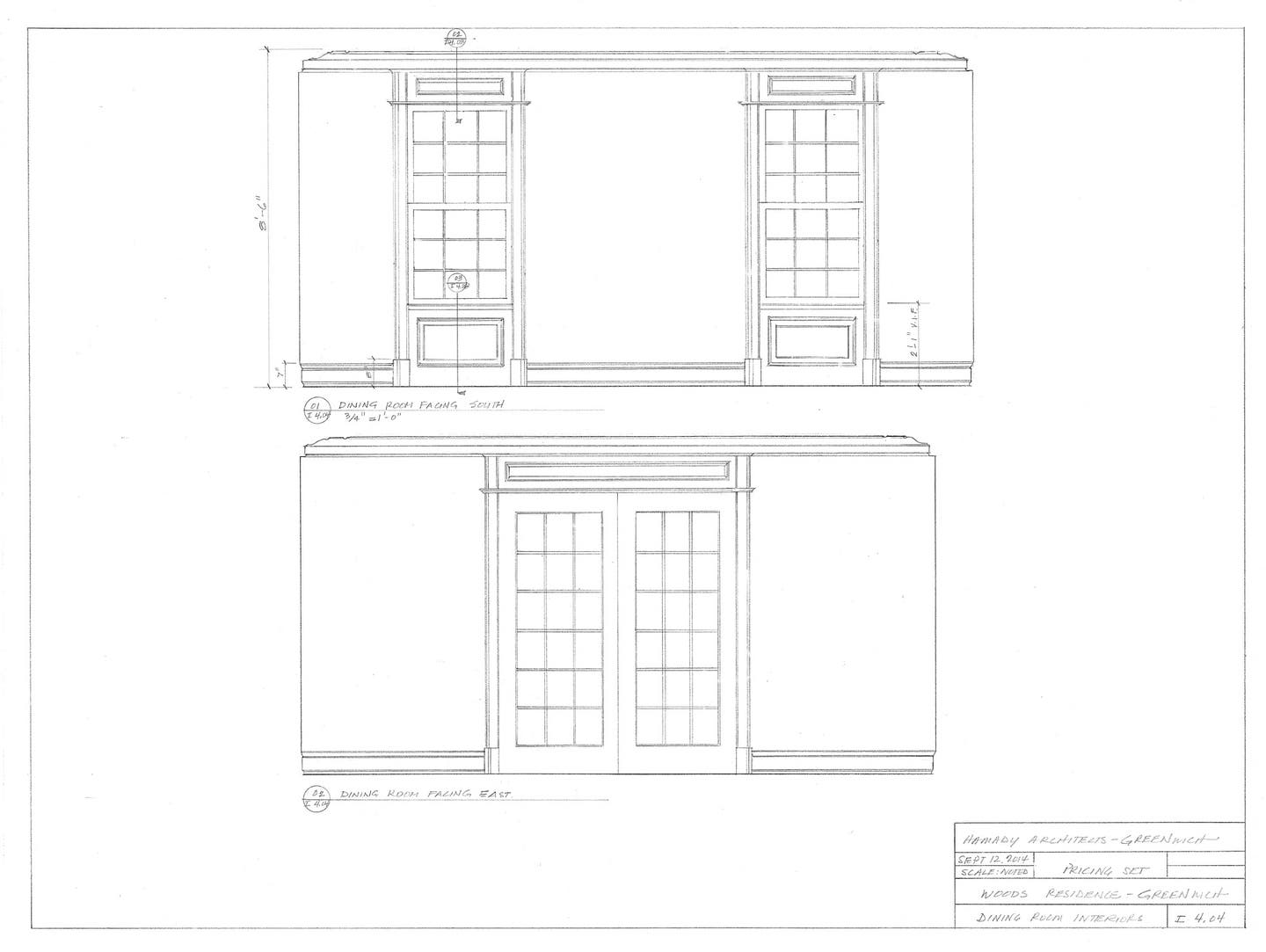

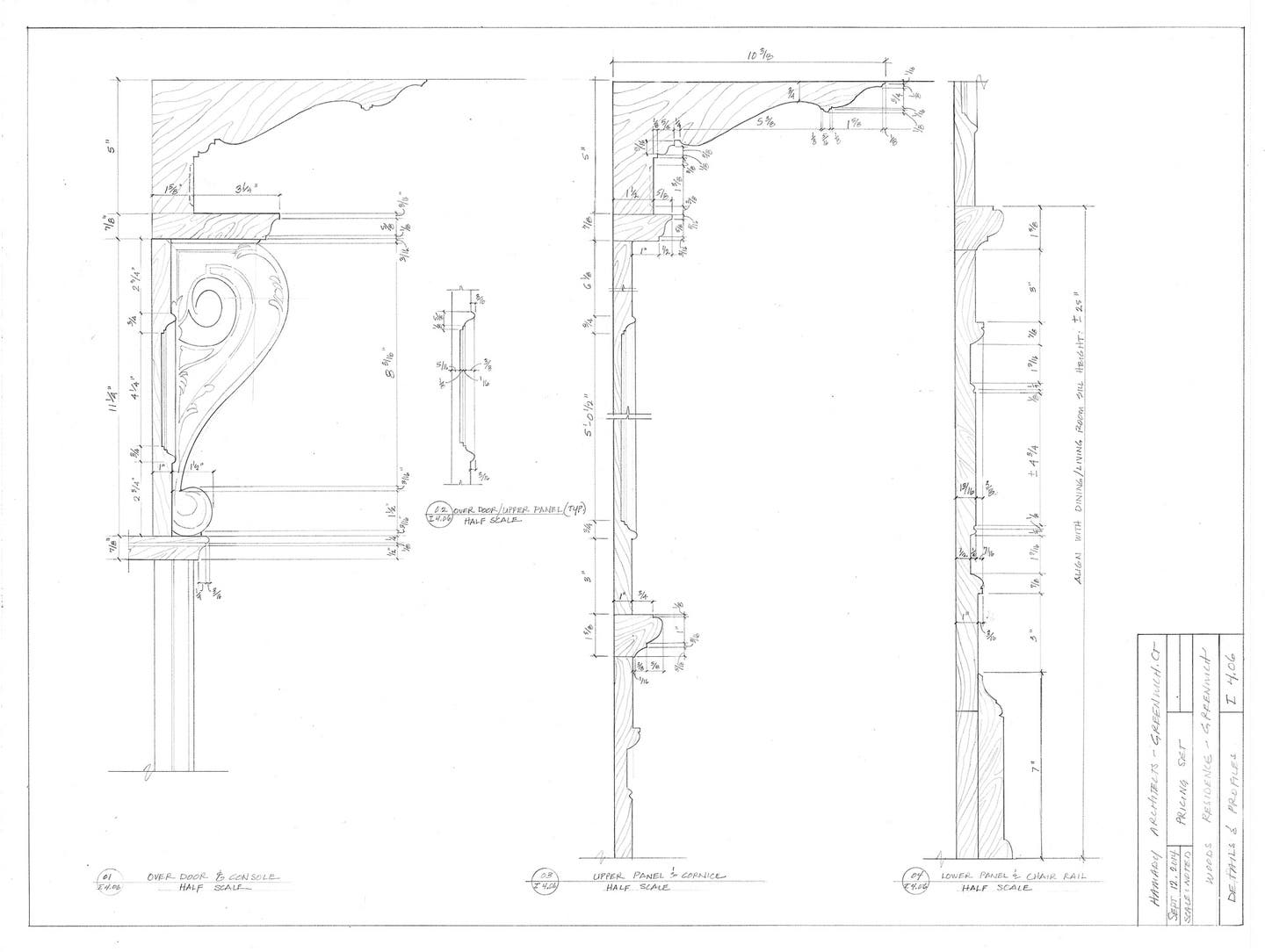

One of the Stanford White Awards, given by the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art in 2016, demonstrates the power that interior details such as moulding can carry. In a renovation and expansion of the 1920s Neo-colonial country house in Greenwich, the Hamady staff applied Classical principles to adjust and improve upon the home’s original design. In the entry hall, for example, what felt like a very low ceiling at just over eight feet, now takes on a soaring sense of space with a cornice moulding and panel details designed to reinforce the verticality of the room.

Vickory asserts that classical mouldings are best expressed in natural materials such as wood, stone, iron, terra cotta, or plaster; as she says: “Classical architecture takes its forms from nature.”

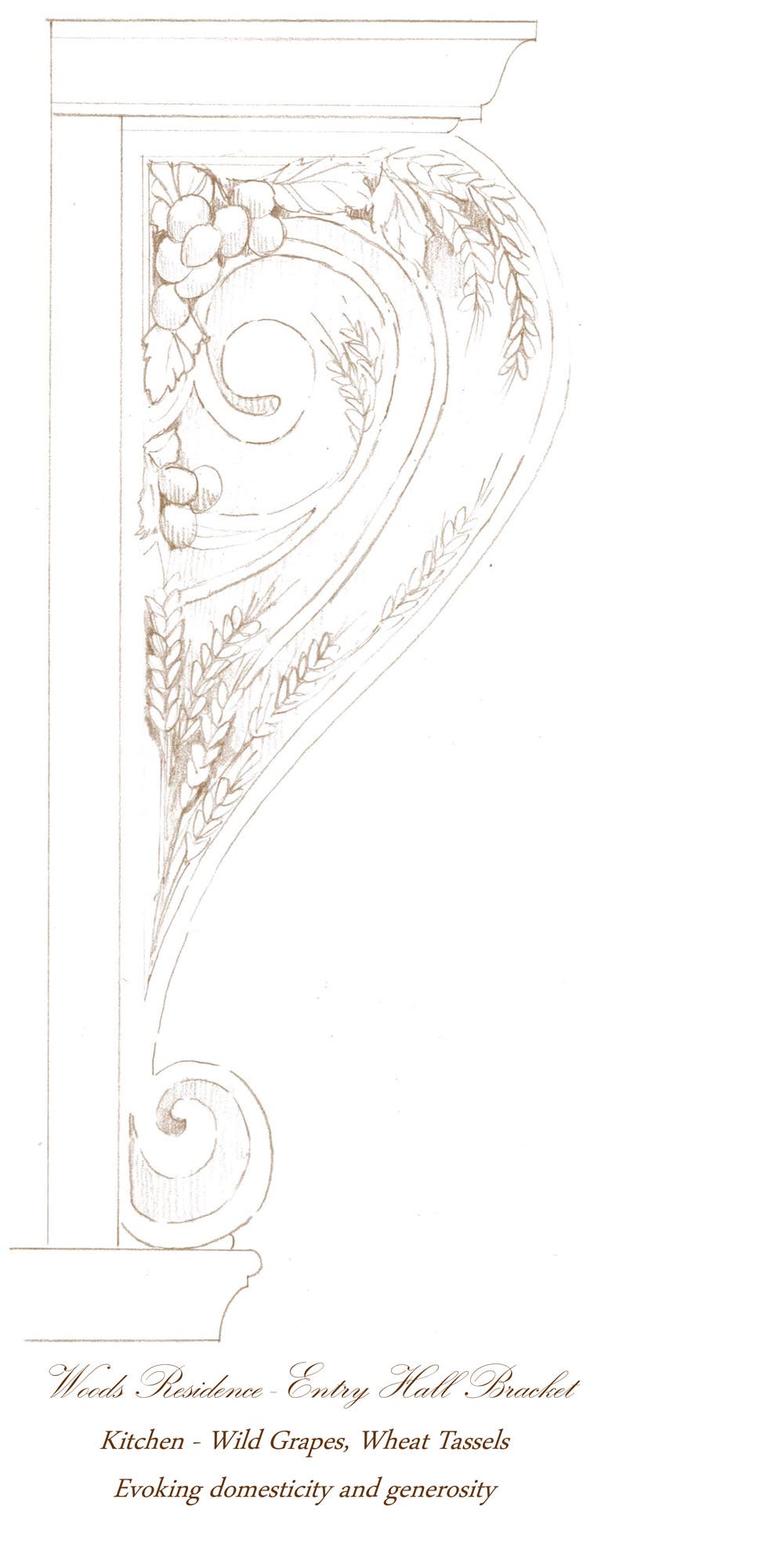

Wood, in all its natural beauty, lends a warmth and intimacy to the Greenwich home. The fireplace mantel and woodwork in the bar are a combination of reclaimed oak, quarter sawn white oak, mahogany, and reclaimed heart pine. Brackets, carved by a Virginia craftsman, support the frame over each of the doors from the entry hall into the dining room, living room, and kitchen. Each set of brackets incorporates a different motif, using symbols from nature such as acorns, feathers, and wheat tassels, evoking strength, history, and generosity.

Moulding also informs furnishings and décor and gives rooms an important hierarchy, she adds. “The interior architecture of a living room will be more elevated than less public spaces, like a bedroom or bathroom,” Vickory says. “It conforms to the principle of decorum or appropriateness.”

While there is a purity of scale and proportion, the Greenwich house also exudes an easygoing spirit. “The house design is not dogmatic,” Vickory says, “but rather a rethink of the space and how to work with it. Classical principles are not mechanically applied.”

Using moulding to help build a sense of artful beauty and ease into a classical interior, as it is in the Greenwich home, is not always easily accomplished. The first step, Vickory says, is to understand the language of Classicism. “Without a fundamental awareness of the Orders and principles of Classicism, or looking to history for precedent, the selection of mouldings is arbitrary,” she says. A sense of scale is also imperative, and bigger is not necessarily better. Choosing strictly by cost, availability, or selecting complex patterns inappropriate to the home can have a very poor effect, she adds.

These are the fine lines that Vickory and her colleagues tread. Their clients notice. “Someone once said, ‘you took the home, dressed it up, and took it to Sunday school,’” she says. “We make it the best it can be. It’s putting its best face on.”

Moulding Study Guides

The study of moulding is an immersion in architectural history. For a seemingly simple interior device, it is steeped in design and meaning. Designer Leslie-jon Vickory of Hamady Architects takes the subject to heart as one that goes beyond quick formulas or mechanical application. However, she says, a few moves can bring depth to understanding. Here she offers a few ways to dip into the subject:

• Read The Decoration of Houses by writer Edith Wharton and architect Ogden Codman. First published in 1897, the book eschewed Victorian flounce and clutter for spaces based on Classical principles of proportion, symmetria, and appropriateness.

• Move on to The American Vignola: A Guide to the Making of Classical Architecture by William Ware. “It is a very simplified encapsulation of the Orders of architecture and their proportional systems,” Vickory explains.

• Study historical precedent regarding domestic and civic scale; in other words, explore fine architecture in situ: “Study architectural interiors standing in the space to understand proportion and refinement of detail.” She particularly recommends 18th and early- to mid-19th century American architecture, Renaissance Italian, and 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century French and English architecture.

• When designing an interior space, develop the habit of using mockups. “You’ll notice how light is reflected, shadow lines are created, how various profiles can either delineate or blur changes in plane,” Vickory says. “You’re seeing how light plays on mouldings.”

• Explore the option of custom mouldings rather than assuming stock profiles will do. “Know you can move beyond stock,” she says.

• Visit the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art (www.classicist.org) to learn more about workshops, travel programs, intensive courses, and publications devoted to the practice and study of Classicism. New England Chapter information: www.classicist-ne.org

• Above all, Vickory says, regard a space in its entirety: its width, length, height, all openings, and the elements within—they must be considered and designed as a whole.

Building Resources:

Decorators Supply

decoratorssupply.com

Driwood Moulding

driwood.com

Caldwell Carvings

caldwellcarvings.com

Enkeboll

enkebolldesigns.com

Hyde Park Mouldings

hyde-park.com

Gaston & Wyatt,

Charlottesville, Virginia

gastonwyatt.com

Zepsa

zepsa.com