Profiles

A Glimpse Into the Life of Architect Phillip Dodd

When I was growing up in England, one of the prime time TV shows was Through the Keyhole, hosted by Sir David Frost—of the Nixon interview fame. The premise of the show was that a colleague of Frost would walk through the home of a celebrity, without revealing whose home it was. Back in studio a celebrity panel would ask Frost questions that he could only answer with a yes or no, in an attempt to guess the owner of the home. The notion being that a house is a reflection of the personality of those that live there—or as Sir Winston Churchill put it, “We shape our homes and thereafter they shape us.”

Why do I note this? Well, if you were to visit my office you’d find hanging on the wall a 12-plate print of the Nolli Plan of Rome, alongside photos of Roger Moore and Michael Caine. And nestled amongst architectural samples and machetes, you’ll find biographies on Richard Burton and Cubby Broccoli, Everton Football Club and James Bond memorabilia, psychedelic photos of the Beatles, and a portrait of the Queen. You’ll not find a similar office anywhere else—just like you won’t find a similar version on me—nor would you want to! Five minutes in my office and you’ll know all you need to about me.

Part of my marketing is my personality—why I differ from others. Note that I didn’t say why that I’m better than others. I dislike the way politicians and society, in general, encourages us to one-up each other in order to engender popularity. I don’t try to appeal to everyone—as by doing that you are diluting oneself. I feel that we live in a time where the goal more often than not is to fit in, rather than to stand out. I’m not advocating that our designs be garish and loud in order to stand out for the sake of standing out—but they do need a sense of identity. This identity comes from the location of the home—its style and use of materials—as well as the personality of the homeowner and the designer. If a client has done their homework, then they’ve hired an architect or designer whose work and language they like. But more importantly, they’ve hired someone that they will enjoy working with, and someone that has a process that appeals to them.

The beginning of any project is like Christmas Day for a designer. However, I try to resist the urge to jump into any design. Instead I press the pause button, and work on two preliminary studies that I present to the clients. The first is a property and zoning review where I analyze the municipal restrictions on the site—setbacks, height planes, wetlands, stories, height, and square footage limitations. It’s always amazed me that every town and city in America has different zoning codes, and its essential to make sure that anything you show the homeowner can actually be built. You’d think that this is common sense, but many years ago I realized how few people actually had any common sense, and rather than being the norm it was actually a skill set!

“I don’t try to appeal to everyone—as by doing that you are diluting oneself. I feel that we live in a time where the goal more often than not is to fit in, rather than to stand out. I’m not advocating that our designs be garish and loud in order to stand out for the sake of standing out—but they do need a sense of identity.” —Phillip Dodd

The second study is a pattern book comprised of historic and contemporary images. For example, for a recent project in Palm Beach, I divided the presentation into sections such as windows and doors, loggias, cloisters, courtyards, and towers. As I showed these images to the clients, I carefully noted which images they responded to—and more importantly which ones they didn’t. You’d be surprised what you learn about each client during this pictorial review, and then know what not to include in your design. With these two studies behind me, I’m then able to hit the ground running. You only get the one first reveal, and these studies more often than not allow me to hit a lead-off home-run.

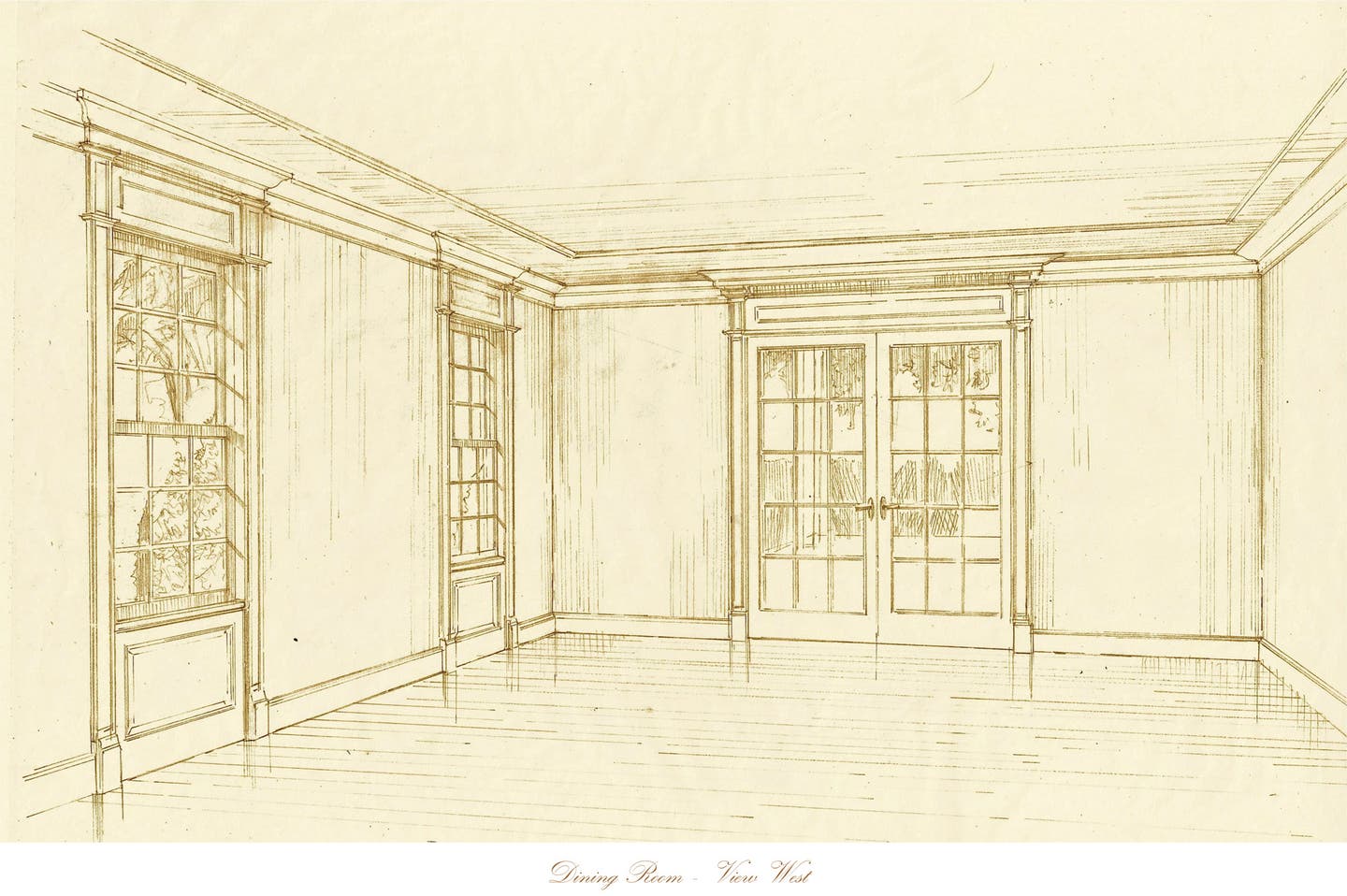

When I was a student in England, and interned in architectural firms there, we drafted with ink on velum. My tools were Rotring pens with different nib sizes, a blade and easer to scratch off and burnish any mistakes, and a hair dryer to dry the ink. When I came to the States, these tools were replaced by clutch pencils, a brush, and proportional dividers. The drawing table remained the same, as did the parallel bar, t-square, and the act of rolling up my shirt sleeves so not to smudge anything. I still do the latter—it’s part of the uniform, as are the requisite eyeglasses. But most importantly, I was still hand drafting.

Why is a background in hand drafting important? This is where I upset half the readers: It’s not a case of improving ones artistic skills. If at any time an architect or designer becomes preoccupied with creating beautiful drawings rather than creating beautiful homes, then they need to change profession and become an artist. Drawings are merely a tool to present the design to the client and to get a home built.

Instead hand drafting allows one to compose a drawing. It’s that eye to brain to hand coordination. When hand drafting, you soon learn to include only the relevant information—no repetition, no useless information. It forces one to self-edit.

Alas, I don’t really hand draft anymore. Instead all project start off with a quick sketch—more often than not a doodle on a napkin in a bar or restaurant. Then my mind works in overdrive as I hand draft in my head, going directly to AutoCAD. That being said, I use an old version of AutoCAD—not because I’m too cheap to purchase a more recent version, but rather because it’s the closest thing I can find to hand drafting. But I’m still drafting rather than assembling, which is, in essence, what the newer versions of AutoCAD do. Just like hand drafting there is conscious thought behind every single line drawn and committed to paper. Nothing is mindless—no cut and paste.

I start off with the plans and if I’ve done my homework correctly, I can limit the amount of subsequent iterations. Plans are functional while exterior elevations are aesthetic—and although it’s essential that our homes look great, the primary concern must always be that they work for the particular idiosyncrasies of each homeowner.

I personally love as many comments as possible during the design process. Mostly, I pay no attention to these comments, but occasionally something will resonate with me. That’s when I stop designing and jump back onto one my writing projects (I’m currently working on a book on the Beaux Arts Architecture of New York City during the Gilded Age). So much of design involves emotions, and this separation allows me to return with a clear mind. More often than not the solution initially suggested to me is flawed—but they have hit onto something that needs my attention. Plenty of designers hate comments or suggestions—but how can anyone ever get better without input from others?

I’ll always give my opinion—whether the clients want it or not—but in the end if a client insists on something, I’ve done my due diligence, and after all, it’s their home not mine. One has to remember that although we are design professionals, first and foremost we are in the service industry.

I then move on to the exterior elevations and building sections. For the most part these are for my own coordinate purposes, as it’s unrealistic to expect homeowners to fully understand and digest two-dimensional drawings. I then use these drawings to create 3D computer renderings as well as a physical model that I present to the homeowner. That’s when the project comes alive in the eyes of the homeowner.

Physical models may not be particularly technologically advanced by today’s standards, but nothing better represents a three-dimensional version of a design. If the budget allows, I work with a great modelmaker in upstate New York who creates wonderfully detailed miniature versions of the design. This is where I should quote a line from Zoolander! But more often than not I will make the models myself. I find this fabrication process to be incredibly informative—and therapeutic. It’s like playing Lego for grownups—and on occasion it makes me pause and reconsider a particular aspect of the design.

Presentation computer renderings represent the culmination of the initial design process. I entered the design profession because I loved to draw, but I’ve learned to put away my own ego and urges to pick up a paint brush, as my artistic skills can’t compete with the computer renderings that I commission. On more than one occasion, these renderings have fooled people into thinking that the home is already built. More importantly, they really are the best way to present a finished design to a homeowner—which is the goal of any drawing.

Then I start on the interior—but that’s a tale for another article.

Phillip James Dodd is an expert on classical architecture and interiors. His residential designs can be found in Greenwich, New York and Palm Beach. He is also the author of The Art of Classical Details and An Ideal Collaboration.