Profiles

Albert, Righter & Tittmann: Building Stately New Homes

Puzzle this: A gorgeous but decrepit 19th-century brownstone in Boston’s South End, radiating history and the tricky problems that often come with age, needed serious help. The homeowner loved his home’s historic exterior—and the city’s regulations wouldn’t allow substantive changes anyway. The interior was another matter; the homeowner wanted it to reflect his interest in Japanese culture. Could there possibly be a happy resolution?

Enter Albert, Righter & Tittmann Architects (alriti.com), housed in a 1902 building in downtown Boston.

The lead architect, John B. Tittmann, AIA, says the team had no idea the direction this client would take them. But, he says, “We knew it would be an interesting experience.” The project team established a thoughtful rapport with the client, including presentations of different types of wood—some weathered, some new—and asking him what it made him think of and feel.

“The design constantly shifted until it was built,” Tittmann says. The end result, which ART Architects refers to as Puzzle House, is a breathtaking joining of architectural traditions of the East and West. “Sometimes being jarring isn’t a bad thing,” Albert muses. “It can be exciting. Not everybody might agree with that. That might separate us from some who are in the traditionalist camp.”

We work in a variety of styles, searching for an appropriate response to the place and the people. We like to say that our houses are portraits of the clients.

ART Architects’ knack for creating an impeccable design that both cocoons and expands the lives of the people inside—whether it is new construction or a renovation—starts with a two-fold philosophical foundation, says principal Jacob Albert, AIA: a deep relationship with the client and careful siting of the house. “We try to make a house seem to sit firmly and comfortably on the land,” Albert says. “We work in a variety of styles, searching for an appropriate response to the place and the people. We like to say that our houses are portraits of the clients.”

Most of ART Architects’ projects focus on building stately new homes with a deeply traditional personality--or ones that combine traditional architecture with other modes. But that doesn’t mean they can be pegged. “Some are symmetrical, and others are asymmetrical,” Albert says of the firm’s designs. “Some tend toward the classical end of the spectrum and others towards the vernacular, while yet others are more modern.”

Like Puzzle House, projects that fold together two or more styles often occur because, as Albert says, “the client wanted to push something.” Consider the house the firm calls Farm Villa. Set in a pastoral stretch of Vermont countryside, the home has some aspects of a traditional farmhouse—white clapboards, deep windows, and a simple gable roof. But then it reveals touches of the formality and elegance of a classical villa, such as its colonnaded porch. “The classical aspects are a simplified interpretation,” Albert says, to reflect the Vermont vernacular.

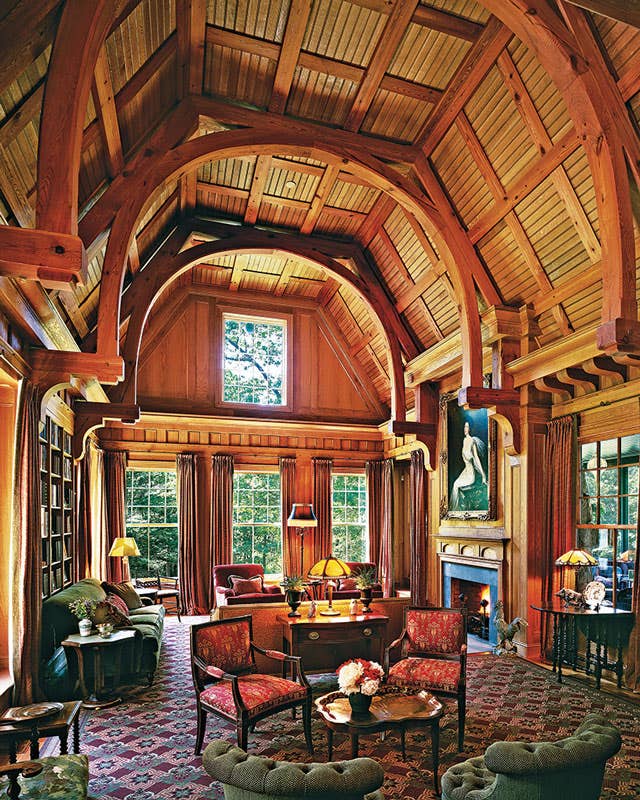

The desires of the clients are also evident in Six Gables, a new house located on the Massachusetts North Shore. They wanted a “sort of medieval feeling,” Albert says. Built of old reclaimed wood, which gives it an appealing burnished color, the house has a bit of a lodge effect. At 5,000 square feet, Six Gables is not as big as it looks; roof trusses and the height of windows amplify its grandness.

Farm Cottage, another New England home design, shows the power of properly siting a home. The white clapboard house, overlooking a farm on the outskirts of Boston, is on a somewhat flat property, so Albert, the project’s lead principal, kept the lines fairly horizontal and low to the ground. The second floor is tucked into a gambrel roof in farmhouse style, the low eaves creating a warm approachability. Drawn through the door, visitors are greeted by an elegant interior with an expansive spirit.

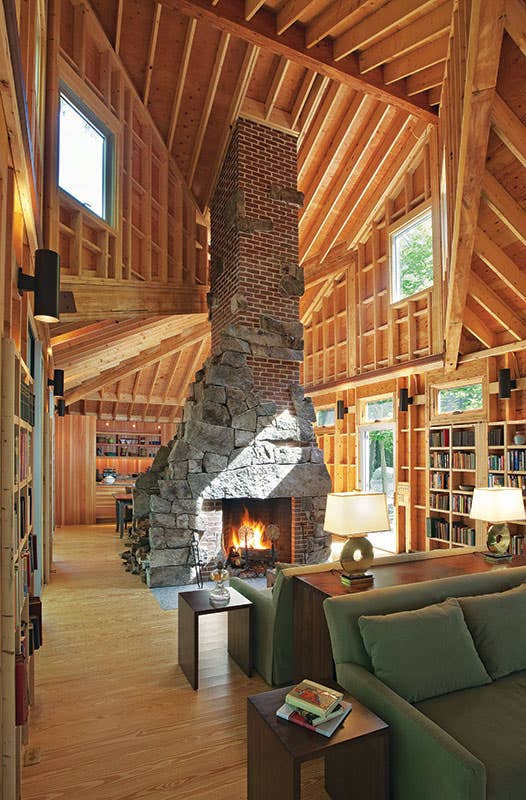

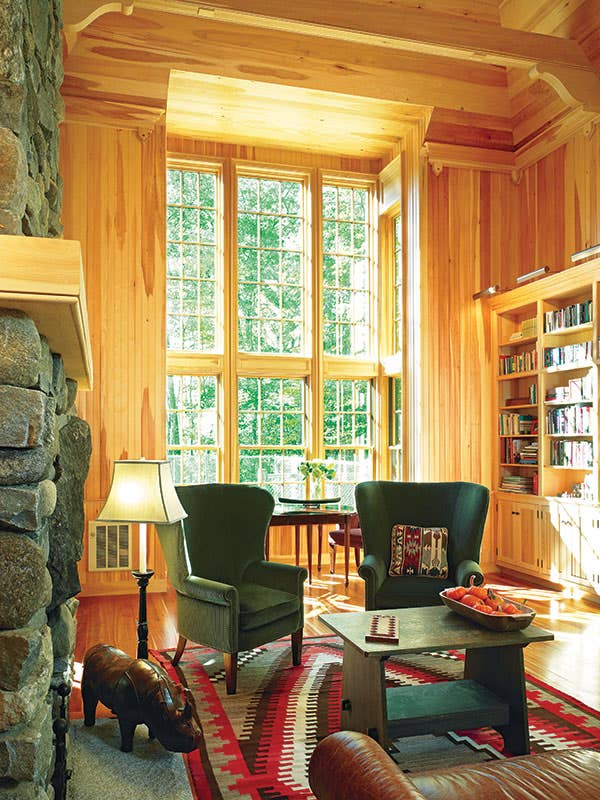

It takes a deft hand to allow a subtle style characteristic to bloom, celebrating a feature that less exuberant designers might hide. In Mountaintop House, a rustic home in the pine forests of Maine, the ART Architects team, led by Albert, let the rustic setting rule.

Buckets of features beg another look: zigzag shapes, exposed rafter tails, decorative work on the roof overhangs, and a long interior passageway topped with an exposed steep fir ceiling and lit with outdoor lamps. The four-bedroom home, measuring about 3,500 square feet, has three different levels, with a guesthouse nearby, all existing in the harmony created by a courtyard. The result is stunning.

Allowing the land to call the shots, and highlighting certain features in beautiful, brazen fashion, requires not just good communication with clients, but a strong connection among the designers themselves. ART’s principal designers—Albert, Tittmann, Jim Righter, FAIA, and J.B. Clancy, AIA—have a similar approach, instilled at Yale’s School of Architecture.

Deep bonds were formed during the early days at Yale. Albert and Tittmann became friends as undergraduates there. Albert was a student of Righter’s in 1975 and joined Righter when he moved James Volney Righter Architects from New Haven to Boston in 1980. “We were turned on by teachers such as Charles Moore and Vincent Scully, for whom John and I were both teaching assistants,” Albert says. “It gives us a common point of view. We’re all working under the same assumptions. Though we don’t have exactly identical tastes, it all fits together. We all are kind of in alignment on pushing boundaries.”

“We talk a lot in the office about how the language of architecture is the response to a place,” Clancy says. “The materials that are used, the shapes of buildings, came out of the tradition of building over time in those places.”

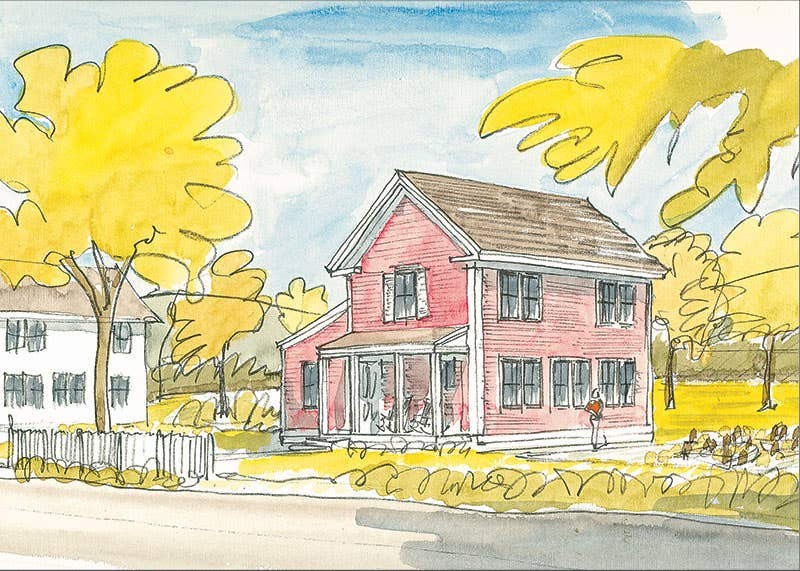

Clancy, who graduated from Yale in 1996, had a chance to bring his fresh perspective to a home that embodies ART’s dedication to environmental construction, a Habitat for Humanity house in Vermont. “It was exciting to provide our design experience and technical knowledge to create a building that would sit comfortably in the Vermont landscape, yet would also employ the latest technology in sustainability and energy efficiency,” Clancy says.

Behind the traditional farmhouse exterior is an energy-efficiency wonder. Super-insulated, pointed toward the sun, and built with 12-inch-thick walls, the home has proven to be very low-cost to operate. Monthly energy costs for heating or cooling often come in at $50 or under. The house, for a family of three, also has a heat-recovery ventilation system and solar thermal hot water system. The project (which ART Architects designed pro bono) was the first certified Passive House Program™ residence in Vermont.

Clancy talks about the philosophy behind the project. “We’ve really been interested in ‘form follows energy,’” he says, “where you can see forms change with the advent of fossil fuels. We looked at the vernacular of Vermont farmhouses and how the farmhouse has been shaped by the climate.” Then the team looked at how to comfortably couple traditional aspects with, as Clancy says, “21st century ideas of insulation, ventilation, and solar energy systems.”

The designers often discuss philosophical topics around how people identify with their homes. “We talk a lot in the office about how the language of architecture is the response to a place,” Clancy says. “The materials that are used, the shapes of buildings, came out of the tradition of building over time in those places.”

Now energy efficiency and sustainability are taking them to new a place in the same subject: how technology coexists with traditional architecture. It has made rich new ground for the ART Architects staff. As Jacob Albert says, “Traditional design and energy efficiency are a match made in heaven.”