Profiles

Past Styles, Present Tense: Eberlein Design Consultants

Style, function and quality. This is the philosophical floor plan that Philadelphia-based interior designer Barbara Eberlein builds into every project.

"The art comes from balancing the past and the present," she says. "The goal is to create rooms that are period in style and that work with the client's lifestyle, following the plans of the original architect and the restoration architect to align everyone's goals."

For the last quarter century, Eberlein, ASID, and her firm, Eberlein Design Consultants (www.eberlein.com), have been recognized for their work in the restoration of prominent public and private buildings in the Philadelphia area, including the Philadelphia Art Alliance on Rittenhouse Square, designed by Charles Klauder with Frank Miles Day in 1906; Villanova University's 1890 Addison Hutton landmark, Dundale; Drexel University's Alumni Center in an 1876 Frank Furness building; and the President's House at Lehigh University, an 1868 Edward T. Potter landmark.

"Our approach is integrative and interpretive of the client's taste, not solely based on our own aesthetic," says Eberlein. "We work closely with the architect, the landscape architect, the artisans and the clients to form a dynamic creative team." Eberlein's approach – a carefully edited blend of new and old – brings out the best from every period. Aside from bathrooms and kitchens, original layouts are largely left intact whenever possible and developed by the skillful placement of furnishings.

"I try to create a logical traffic flow appropriate for 21st-century use, even when we need to accommodate a lot of furniture and challenging demands," she says.

Even Eberlein's most opulent and glamorous rooms are meant to be lived in. Fragile fabrics, for instance, are used in areas of high visibility but low use, and museum-quality furnishings are placed strategically next to sturdy pieces designed to live and work hard.

"Most of my clients have children or grandchildren," she says, "so I present a 'now' plan, a five-year plan and a 15-year plan so as the members of the family grow, they create their own history and the beauty of the home lives and grows with them."

Enlarging a Georgian Townhouse

In the restoration of an historic Georgian brick townhouse in Bethlehem, PA, Eberlein had to think small to make the home live large enough for its occupants – a father and two teenagers. Every square inch of the 2,800-sq.ft., ca. 1848 house had to be put to good use and in a short amount of time.

"The owner wanted it done in a few months," says Eberlein. "But I convinced him that with restoration it's very valuable to take your time; there are always surprises, and we want them to be happy ones."

With a collection of 19th-century American paintings, the owner had a strong desire to bring the interiors back to that period. "He wanted to restore it to a level of aesthetic confidence that may not have appeared in the house in decades," says Eberlein, adding that the home's understated architectural elements, including its simple moldings, became the key to the project. "Instead of embellishing them, we allowed the wall, ceiling and floor planes to take precedence."

This meant that in the dining room, the ceiling was covered with a period-style paper with geometric architectural motifs that raise the ceiling by providing three-dimensional depth. The master bedroom's wallpaper, another historic style, uses a bold pattern to enlarge the space. And the entrance hall's paper, a serene ivory ground with a gold, red, blue and green pattern, reflects the simplicity of the architecture and the prevailing color palette, which changes with each room.

"The introductory spaces are so important in establishing character, and they frequently are dismissed as merely spaces to move through," says Eberlein. "As the hub of the house, they need the most character. That's where you pull all the design messages together."

Eberlein's big "small" ideas included turning several spaces into multipurpose rooms. The dining room, for instance, also houses the library, which is displayed in full-height millwork with classic details. When it came to furnishings, Eberlein made bold choices. "I used fewer objects, but they were larger and had simpler lines, like the 19th-century chest of drawers in the master bedroom," she says, noting that working the small space for all it was worth gave Eberlein the opportunity to expand its vistas. "The whole idea was to create the illusion that there's something beyond the physical space."

A Grand Scheme for Comfortable Living

Grand homes demand grand plans but don't always require a grand lifestyle, and so it was that Eberlein skillfully created a comfortable family home in a 20,000-sq.ft. 1920s house designed by Ralph R. White, in Villanova, PA.

The three-story house had, long ago, been converted to a convent. Radical adjustments were necessary to make it into a livable residence for a mother and her growing son. Once the church pews in the ballroom were removed and the dozen showers in the top-floor servants' quarters were taken out, Eberlein began the eight-year task of bringing the mansion back to its glorious past.

The original utilitarian kitchen cabinetry was moved to the top floor and converted into an art studio for the mother and son, both accomplished painters. On the second floor, the bedrooms were reconfigured into suites that include baths, dressing rooms and sitting rooms. The first-floor kitchen was remodeled and enlarged by incorporating four tiny rooms, including the butler's pantry, and adding a breakfast room that nestles into a substantial bay window. And in the ballroom and the terrace room, originally separated by doors, pairs of double columns reconnect the indoor and outdoor experiences.

"The interior of the house incorporates many architectural styles that range from the robust and masculine to an airy, ephemeral, feminine look," says Eberlein. "Each room has a character that is identifiable." The larger rooms were divided visually by the placement of furnishings. The 25x35-ft. ballroom, for instance, was transformed into conversational settings, one of which includes the grand piano. Historical references include drapery and upholstery fabrics based on period documents and plush seating furniture decorated with tassels and wide fringed skirts.

"We added to the architecture by stenciling around the ceiling," says Eberlein. "This was a gentle way to project color onto the ceiling and to bring the scale of the room down a bit. It's actually cozier now than the original living room."

The dining room, which originally was designed to seat 38, got a similar scale-down: It was divided to include a sitting room. "This is where cocktails are served," Eberlein says. "It's a most practical addition because there's now a clear pathway through the room to the kitchen."

Thinking Ahead While Looking Back

One of Eberlein's more challenging projects was the restoration and renovation of her own home, a five-story historic townhouse in Philadelphia. The 1851 building is small – 19 ft. wide and 70 ft. deep – but Eberlein had a lot of leeway because when she bought it, the interior had been demolished. "All that remained was part of the staircase," she says. "I had to think, 'What did it look like when it was built?' and 'What do we need it to live like?'"

At the time, she and her husband had two babies, so she had to anticipate future needs. The back of the house had a 4½-ft.-wide breezeway that soared to the roof, so she took that space and converted it into an L-shaped kitchen, master bath, studies and a deck.

"My goal was to celebrate exuberant design and do all the things I'd always wanted to do but that no client had ever asked for," says Eberlein. "I made the dining room walls blue – everyone always wants warm, rosy colors – and I furnished the whole house with antique furnishings from some of my favorite periods, including 19th-century Italian."

The living room, furnished in late-18th-century English and French pieces, includes a grand piano, a wet bar, two seating groups and a library with shelves that rise to the ceiling, providing space not only for books but also for the television and sound system. Eberlein's plan has worked well – she still lives in the house and recently reconfigured the lower level to accommodate her studio.

Restoring a Grand Old Dame

When a house is of a certain age and reputation, determining how far back to take it in time isn't always a cut-and-dried decision. In the case of Ardrossan, a 1912 Georgian in Villanova, PA, designed by Horace Trumbauer, memory more than history was the guiding hand. Set on 400 acres, the three-story, 38,000-sq.ft. house and its 26 outbuildings had remained in the same family since it first opened its enormous front doors.

"The grandson, who was heading the project, wanted it to look just as it did when he was a child," says Eberlein. "He envisioned a grand old lady who looked her age." The original furnishings remained, but some had seen a lot of happy days and hard use during their century of life, so the project focused on restoring the furniture, paintings, decorative accessories, and where possible, the fabrics.

"We didn't want anything to look new, but we wanted it to look well preserved," says Eberlein. "The fabrics had to look aged, floors couldn't look too polished and plasterwork couldn't be too pristine."

In this restoration, the first floor retained the public rooms, which remained entertainment centers; the second floor became an apartment for the owner's niece; and the third floor, which had been the nursery and servants' quarters, became the owner's suite. Eberlein's historic predecessors – the original design firm White, Allom & Company, which decorated Britain's Buckingham Palace, and the prestigious Parisian decorator André Carlhian, who added French flair in 1930, laid the groundwork for her work.

"The owner wanted every piece of furniture placed exactly as it had been," says Eberlein. "Usually we just rely on photographs, but here, we also had his memory and the exquisite petit point pictures that his grandmother had made of every room to guide us."

Traditional Marriage for a Georgian Mansion

When Portledge, a ca. 1909 Georgian mansion by Horace Trumbauer, got a new, young owner, he wanted to restore it to its finest hour. In this case, there wasn't much to go on: None of the furnishings survived, and no one recalled what it looked like inside. But enough of the woodwork and plasterwork were intact so missing pieces could be filled in easily.

"The owner, who collected antiques and art within a broad range, did a lot of research, and he wanted to restore it slowly, room by room to see how he would really live in it," says Eberlein. "But once we got going, he couldn't stop."

To fit a young lifestyle, the basement was converted to an entertainment center that includes a wine cellar and wine-tasting room, media room, lounge and billiards room. The public rooms of the first floor were retained intact. The second and third floors were reserved for bedrooms, a library and offices.

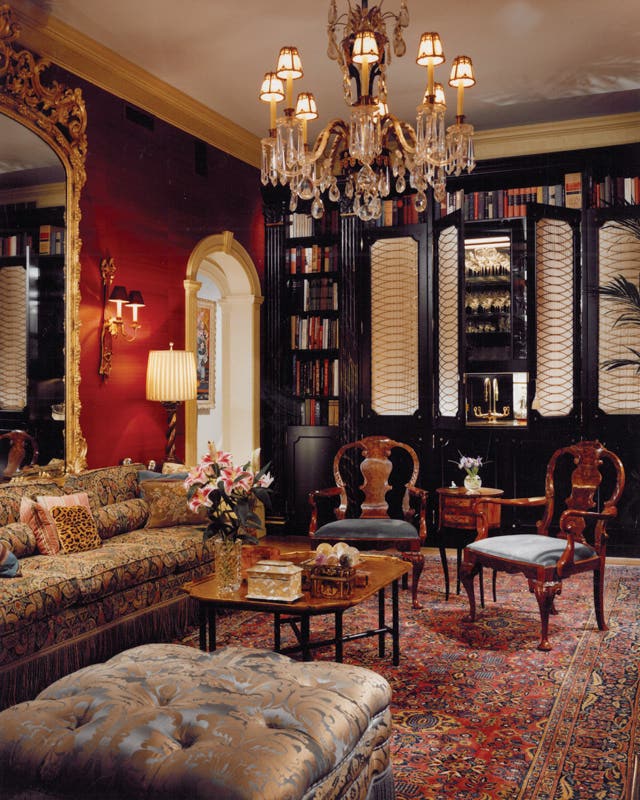

"We didn't have any furniture, so we started going to auctions and antique shows, and we bought pieces from virtually every continent," says Eberlein, noting that the living room set the tone for the other rooms. "He wanted something comfortable, cozy, masculine, and most important, livable."

Eberlein furnished the room with English antiques and new, lushly upholstered traditional seating furniture and used dramatic jewel tones – reds, blues and greens – and highly textured textiles, including velvets, to create visual and physical comfort. "These fabrics are extremely durable," she says. "They still look great after many parties."

The larger rooms in the 21,000-sq.ft. home were furnished with several conversational seating areas, "where six to eight people can talk and really connect." The project was finished just in time for the owner's wedding reception, which was to be held in the house.