Profiles

Natural Palette: Landscape Architect Gregory Lombardi

By Nancy A. Ruhling

“Designing a landscape is like studying a piece of art,” says landscape architect Gregory Lombardi. “You find its meaning – in its color, form, texture and choice of plants – by analyzing it and asking yourself what story it tells.” It is no accident that Lombardi, founder and president of the Cambridge, MA, firm that carries his name (www.lombardidesign.com ), approaches his work with an artistic eye: He has an undergraduate degree in art history and since childhood, has had an abiding interest in art and historic preservation. These passions fuel his design philosophy, which calls for “the fresh interpretation of classic, timeless principles to create meaningful spaces.”

For the more-than-two decades that he has been painting with plants, Lombardi has established himself as a master of residential projects, whether he is designing a Boston roof terrace, Cape Cod compound or Palm Beach condo. “The homeowners I work with are not clients, they are patrons,” he says. “They have remarkable physical locations that allow me to create unique interactive landscapes. My gardens are works of art, and I approach them seriously. I don’t waste gestures or add a line that doesn’t tell a story. I’m a good editor – I don’t waste time on something that doesn’t propel the plot.”

Lombardi notes that his “living canvases” provide a unique sensory experience that is not only visual. “There are auditory and olfactory elements that evoke feelings and memories,” he says. “For instance, when I smell lilacs, I remember my grandmother’s house.”

A self-described “Nature Boy,” Lombardi was taught the beauty of the blooms by his grandfather, who every spring took him to pick out plants at a friend’s greenhouse. “This cultivated my interest,” he says. “I could buy whatever I wanted as long as I planted it. I learned that you have to be patient with gardens.”

Rather than adhering to one “absolute style,” Lombardi explains that his projects, most of them in the Northeast and Florida, possess a defining “rigor or discipline” and a “level of thoughtfulness, detail and craftsmanship” that set them apart. “There is no one style that dominates the design,” he says. “All contexts are considered for synergistic impact.”

In many cases, he works closely with architects and is integrally involved in the design of master plans that meld indoor and outdoor spaces. “The creative challenge for me is pulling all the disparate elements together to make a statement,” he says. “I’m orchestrating the entire environment.”

“The most interesting aspect of gardens is their ephemeral pieces. They make you aware of your own mortality by providing seasonal markers that illustrate the passage of time. It is sad when flowers pass, but they make you aware that you are sharing the planet and waiting in anticipation of an awakening.

Lombardi’s design process is straightforward: After consultation with the homeowner, he develops a schematic master plan and design layout. “It is important that people understand that you don’t have to do everything at once,” he says. “When you have a plan, you can phase things in.”

Unlike houses, gardens are not forever, and that only makes them more alluring to Lombardi. “The most interesting aspect of gardens is their ephemeral pieces,” he adds. “They make you aware of your own mortality by providing seasonal markers that illustrate the passage of time. It is sad when flowers pass, but they make you aware that you are sharing the planet and waiting in anticipation of an awakening.”

It is nature’s inevitable alterations that Lombardi finds so compelling. “Whether the garden lives beyond the owner is irrelevant,” he says. “It will change and grow and touch other people in different ways.”

Lombardi would like to think, though, that his designs “prove so timeless and universal that the new owner recognizes their power and deems them worthy of preservation.”

Wild Restraint

The new house was a strait-laced red-brick Georgian, the type of traditional residence that simply called out for a no-nonsense, Classical landscape. But the owners, a couple with four active adult children who declared themselves “informal people,” wanted none of that. They saw their 1.9-acre Brookline, MA, country estate, which originally had been designed by the venerable Olmstead firm, as a more relaxed setting and commissioned Gregory Lombardi to create traditional spaces that weren’t quite so strict.

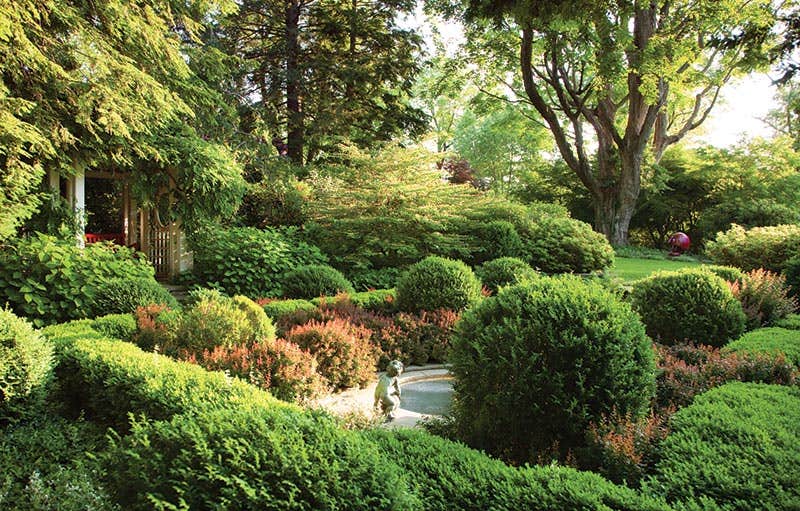

“The owners wanted a slightly overgrown and romantic look that was playful,” Lombardi says. “They saw the property as a lush, languid English country estate.” Drawing upon the work of Edward Lutyens and his collaborations with Gertrude Jekyll, Lombardi came up with a master plan that carved out distinct areas, or rooms, according to the Classical tenets of symmetry, order and proportion and used lush plantings to soften walls and paths set on rigid geometric grids.

Each room takes its cue from the architecture, a device Lombardi used to extend the living quarters outdoors. “The further you go from the house, the less formal the spaces become,” he says.

The tone is set at the street side, where Lombardi designed a pair of 9-ft.-high red-brick piers that support a custom wrought-iron and bronze gate that draws attention to and frames the home’s front door. “This was done in homage to the original drive,” Lombardi says. “It is my civic gesture to the neighborhood.”

The closest garden room to the house is the Family Terrace, which is designed for casual dining and entertaining. To link it, the most architectural room in the garden, to the house, it is paved with the most intricate pattern of interlocking brick and bluestone circles on the property, which Lombardi designed to create a tapestry effect.

Herringbone brick walks connect to the Cocktail Terrace, where a pergola softens the height of the building and offers shade. Radial, monolithic bluestone steps signal and soften the change of direction, connecting the great lawn and pointing toward the Olmstead flowering knot garden, which was planted on the remains of the original. The space, which the owners like to keep un-pruned, features a dainty circular pool guarded by a cheeky cherub and a fire engine-red wooden swing sheltered by an arbor abloom in purple wisteria.

“As the red swing and purple wisteria show, the owner is not afraid of color,” Lombardi says. “We kept everything green and white and added accents of red so it has a surreal ‘Alice in Wonderland’ feel.”

The elliptical swimming pool, anchored by a wooden clapboard Classical-columned pool house painted white, sports three sections that encourage progressively active pursuits. Its brick terrace opens to a hot-water spa that features a runnel fountain that cascades over bluestone slabs layered like a cake into the swimming pool.

The tennis court, reached via a casual set of steps and a stepping-stone walk, houses a shed that, peeks from behind a folly formed of foliage.

“Every time I visit the owner, and we walk around,” Lombardi says, “I always say, ‘Let’s cut these back a little’ and the reply is, ‘Can’t we just let it go?’”

Yea! Is for Horses

The 10-acre horse farm, which is in the western Boston suburbs, has been christened Beechwood, the name reinforced by the newly planted pair of beeches that stand sentinel over the indoor riding arena.

As the horse trots, the family residence is only a quarter mile away, and the owners wanted to make it as sophisticated as their own home. “They wanted it to be timeless and to look as though it had been there all the time,” Lombardi says. “They paid the same attention to detail and craft on the farm as they did to their own home because they saw it as an extension of family life. They never said, ‘This is just for the horses.’”

In addition to landscaping, Lombardi’s firm was called upon to design the layouts of the roads, the grading, the walls and fences and to help the architect with the siting of the buildings, which include an indoor riding ring that is as large as an industrial building, a 12-stall horse stable and a quaint stone service barn/guest house.

“We did a lot of research on plants that aren’t poisonous to horses,” Lombardi says. “That’s why we chose beech trees and made them our theme. They are naturally majestic and large.”

The arena’s outdoor courtyard is a prime feature of the project. The style-defying building, which Lombardi describes as “simple and honest in presentation,” features a metal roof, heavy timber support pieces and post-and-beam construction.

To ground it, Lombardi designed a 25-ft. grassy square that is bounded by a border of New England granite and centered by an antique millstone. It is surrounded by long-wearing, 4-in.sq. cobblestones that give way to larger slabs of granite. This sea of green gives horse and training trailers ample room to turn, and stands up to the occasional tire tread. “It feels hefty and powerful,” Lombardi says. “Its wide border and banding give it a rough-hewn nature that is in keeping with the horse theme. And the different types of paving materials break up the courtyard’s massing.”

A 2-in-1 Solution

Oftentimes, gardens become lost to time, and such was the case with those at a Beaux Arts/Romantic Revival townhouse on a prominent street in Boston’s Back Bay. The historic five-story mansion had been expanded to include the townhouse that was attached to its back when it was converted to condos. When Lombardi saw it, the street-side garden, which was encased by an antique cast-iron fence, was history.

“We had to ask ourselves, ‘What would have been there originally?’ and work from there,” he says. “I pictured an Italianate or French parterre garden that was neat, tidy and clipped.”

That would have been well and good a century ago, but there’s an old magnolia tree on one end of the property that has become somewhat of a tourist attraction. “It is really beautiful,” he says. “Most of the other magnolias are pink; this one is white, and people take their wedding pictures in front of it.”

To address this challenge, Lombardi designed the garden into unique but complementary segments along the two façades, one of which incorporates the white magnolia. Creating the design in this way, he says, reminds viewers that the townhouses, one buff sandstone, the other pink sandstone, tell two stories.

To reflect this, he balanced each end of the boxwood-bordered parterre with a topiary fashioned from a non-hardy privet, and further tied the two with ivy – “just enough to soften the walls and create a cool, green vertical line.” A pale pink rosebush in the center circle of boxwood references the hues of both buildings. The interior spaces are filled with annuals that are changed with each season. “We fill them like vases,” he says.

To accentuate the Classical form, Lombardi put a great deal of detail into the border’s hard edges, letting the stone curve to keep it married to the hedge. “This project was like doing a geometric proof,” Lombardi says. “It was seamless and tight.”

Lombardi also designed an outdoor garden space in the original coal-delivery corridor at the back of the townhouse. He covered the heavily damaged brick walls with trellised mahogany woodwork that was painted a black-green and used what he calls “a mixed tapestry of plants” in a classic palette of dark green and white to bring an air of tailored elegance to the courtyard garden.

Relaxing All the Rules

Vacation homes are made for relaxing, and Lombardi kept that in mind when he landscaped the waterside property of a new Shingle-style home in South Dartmouth, MA.

With four active children, the family is a busy one, and “they come here to be off the grid in a sophisticated way,” Lombardi says. “It is their seasonal beacon.”

Lombardi devised a plan that shows off the simplicity of the four-acre property and retains its natural understated beauty. A big, sweeping lawn, complete with towering oak trees that have been there hundreds of years, defines the space.

“This project was less about the gardens than about creating venues for orchestrated experiences that range from bike riding and lawn games to swimming,” he says.

To round out the plan, Lombardi created a Classical garden with traditional landscape forms that is sited close to the house. This garden room, which is visible from the kitchen window, opens to terraces and the water beyond. The swimming pool forms another room.