Profiles

Peter Pennoyer’s Classic Home Restorations

Peter Pennoyer, FAIA, has a visceral love for New York City, in all its grit and glory. It is where Pennoyer grew up, where he first witnessed the beauty of neighborhoods, and where he experienced his first big architectural blow.

Pennoyer grew up in an 1870s townhouse on 65th Street, in a block where classic neo-federal homes stood next to European tenements and quirky shops. All the structures backed onto leafy gardens, a bit of pastoral heaven in the urban environment and a view shared by the whole neighborhood, no matter who they were.

It was an eclectic and beautiful statement about people and the places they inhabit. “It was a wonderful thing to see these buildings creating a common streetscape,” Pennoyer says.

When Pennoyer was 13, a developer knocked down the tenements and built an apartment tower, a sterile mass of concrete and brick that loomed over the neighborhood’s common green. The fact that someone could figuratively bring an entire neighborhood to its knees hit Pennoyer like a thunderclap. “This was a shock,” he says. “I remember being discouraged by this thing, looming at the end of our backyards. It was a turning point for me, realizing this city could be changed that way.”

Today, that realization still supports the professional intentions of this Columbia-trained architect, who was named a named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 2014. The principal of Peter Pennoyer Architects (PPA) (www.ppapc.com), headquartered in Manhattan, Pennoyer and his staff of 64 are dedicated to creating traditional home designs that allows neighborhoods and other settings to sing—whether the project is a historic renovation, a new home, or a small development of townhouses.

Pennoyer and his associates—partners Jennifer Gerakaris, AIA, Elizabeth Graziolo, AIA, Thomas Nugent, AIA, and James Taylor, AIA, along with design director Gregory Gilmartin—oversee designs that have the heft of substantial architecture but that also carry surprise, wonder, and sometimes, a sweet little secret.

Consider Drumlin Hall, a gracious, traditional stone house in a pastoral sweep of the Hudson Valley in New York State. Pennoyer and his staff designed the 7,500-square-foot country house as a Palladian villa, which also means, in stark terms, that it is very much like a cube. “The issue becomes, how do you get light into the middle of a cube?” Pennoyer says. So the architects placed a graceful staircase, with an artful garlanded balustrade, in the home’s interior, and a skylight at the top, effectively creating more room for windows and spilling light over the staircase area. “It’s something that’s not obvious when you walk into the house,” he says.

“There has to be some real personality, to make them feel alive, warm, and inviting,” Pennoyer says. “Otherwise we’d be reduced to pattern books.”

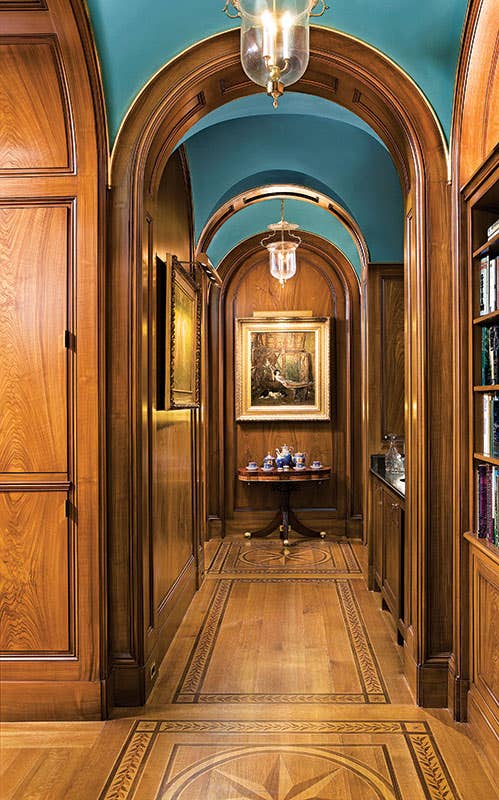

The light-filled interior of Drumlin Hall is buoyed by the openness of the living room, dining room, and library, conducive to spirited parties and company. In the library, a working bar is hidden behind a hallway’s discreet panels.

Sometimes the best surprise in PPA designs is the way the designers are challenged to follow nature’s own bold course. A shingle-style camp-inspired home in New York’s Adirondack Mountains trumpets the simple beauty of natural materials—a stairway of peeled logs, jute, and reclaimed boards; a bedazzling fireplace of uncut stone; rustic interiors of cedar, beaded board, and painted wood.

But the feature that may showcase nature at its best—and presented the greatest challenge to Pennoyer and his colleagues—is its site, a narrow rocky channel between two islands. “It was a very challenging site, a bending ridge of granite, almost cliff-like,” Pennoyer says of the 2005 project. “So we had the plan follow the bend of the outcropping of rocks.”

The result is a house that relates to the land and turns the art of living into a dynamic experience. As a person walks through the rooms, there is an unconscious following of the site’s jagged lines. “You’re forced to turn a bit without realizing you’re following the shape of the land,” Pennoyer says. “It seems very alive. It feels very much like being on a ship.” At the same time, the home’s modest exterior is perfectly in keeping with the area’s history and identity, built on fishing and farming.

Another project, Diamond A Ranch in New Mexico, held very different challenges. When PPA architects entered the project, the property was a haphazard compound in a jangled mix of styles. The main house, built in territorial style, clashed with historic buildings on the site, including a former stage coach inn and a chapel. Work had been done that was not true to the original form and materials, Pennoyer says. PPA’s restoration corrected that, including a gutting and rebuild of the main house that incorporated adobe and floors of waxed clay and dirt. Architectural pieces, such as a campanile salvaged from a Mexican church, draw the structures together for an inspiring whole.

The common thread among the projects is a creative, soulful balance of history, modernity, and a sense of belonging. “There has to be some real personality, to make them feel alive, warm, and inviting,” Pennoyer says. “Otherwise we’d be reduced to pattern books.”

It all starts with intense collaboration of PPA staff and their clients. “Everything in my office is a collaboration,” Pennoyer says. “We listen to people’s requirements really carefully, how they plan to use the house.” It’s not unusual, he says, for clients to get a pre-project questionnaire with seven queries that relate to the inside of a shower. Marrying the functional requirements with design, he says, is where professional satisfaction lies: “That’s where the magic is.”

Most of PPA’s projects are in the U.S., but lately Pennoyer has been traveling to Hong Kong for a project in a neighborhood called “The Peak,” a cluster of five townhouses overlooking Hong Kong Harbor and hugging a steep mountainous incline. “Almost everything old has been torn down, which makes it hard for me,” Pennoyer says, “but people are coming around to traditional design.”

Preservation has been crucially important to Pennoyer. After earning his first degree, in a program led by his lifelong mentor, Robert A.M. Stern, Pennoyer worked for Stern himself, later starting a design studio with a friend that focused on renovation. His father, Robert Pennoyer—still a practicing lawyer at age 90—came home with copies of architectural presentations given in the 1960s before the New York City Art Commission. That, and the poorly executed development of his childhood Manhattan neighborhood, are driven as much into his principles as any formal training. He talks passionately about his favorite New York buildings—Lever House, the Seagram Building, the (Pierpont) Morgan Library & Museum, the New York Public Library—all designed to elevate the living that happens inside.

“They are wonderful harmonious buildings,” Pennoyer says. “It’s the vitality and inclusiveness of real architecture. There’s always more to see and understand.”