Profiles

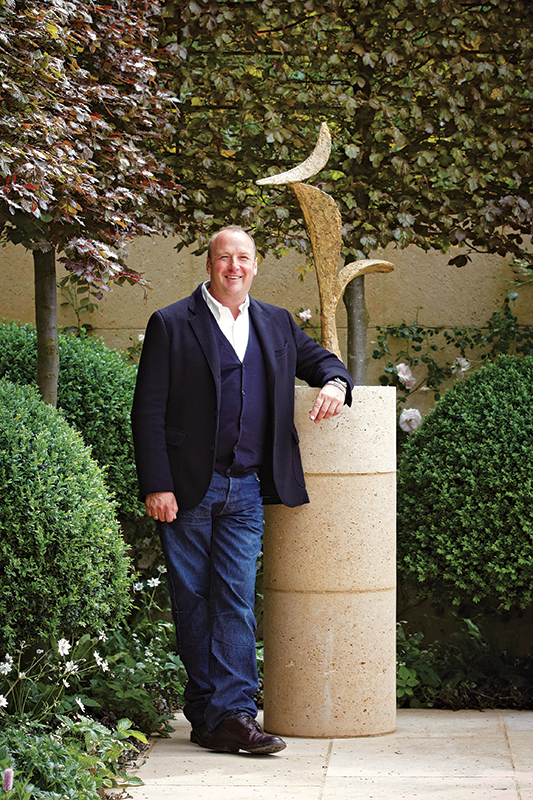

Garden Designer Arne Maynard’s Dramatic Landscapes

“There’s no difference between working in the States, in England, or in the Middle East,” says award-winning garden designer Arne Maynard. “It’s about using the right vernacular details and the appropriate plantings for the area—the design stems from that.”

Maynard is first and foremost a gardener. While growing up, he spent a lot of time with his mother in her garden and often visited his godmother, who owned a large garden nearby. They instilled in him a love for sowing seeds and watching them grow—and grow they did. By 1990, he was helming a London–based garden design practice and working on a range of commissions—from small urban plots to sprawling country estates—both in the United Kingdom and abroad.

Over the years, Maynard has developed a reputation for employing certain design elements. His signature gardens use scale to great effect and are full of juxtapositions of old and new, hard and soft, trained and wild. Topiaries and pollarded and pleached trees create dramatic appeal and make large-scale punctuation points that anchor a garden much like hedges, but are infinitely more engaging and playful. “I see the trees as the main players in the garden—the sentinels at entrances or the characters of the main design,” he says. A love of wild flowers and species bulbs is also evident in his work. Creating year-round interest is something he strives for as well. “I build strong architectural elements into my designs, which form the backbone of the garden and are most apparent over winter.” Come summer, the garden loosens, giving way to its more feminine features.

“There’s no difference between working in the States, in England, or in the Middle East. It’s about using the right vernacular details and the appropriate plantings for the area—the design stems from that.”

A Maynard garden is one that appreciates and harmonizes with the onsite architectural elements. “Architecture and landscape design are inextricably linked,” he says. “One cannot exist without the other.” No matter the style of a building or the characteristics of its greater landscape, the garden must relate to both. To ensure this is the case, Maynard often works in tandem with architects, collaborating on their respective design ideas to form a cohesive whole.

To create paths, walls and perimeters, entrances, and areas of interest within a garden, Maynard employs vernacular materials crafted using traditional methods and techniques. Take stone, for example. Looking to any given region for cues, he’ll determine what’s commonly used in buildings and boundaries and use the same. “If brick is the prevalent material, we will use brick and we will try to source [it] from traditional craftspeople, using traditional methods to make modern materials.” Additionally, Maynard himself, designs oak and painted-timber garden furniture and accessories, which are “based on simple, traditional shapes” and made by craftsmen at Haddon Hall in Derbyshire using English oak that’s grown and aged on the estate. “It is important that we can tell the story of a garden, including the [handmade] elements we bring into a design,” says Maynard. The same craftsmen make the posts and gates he is known to use.

“I also love working with bronze—it is an expensive material but one which sits so naturally within a garden setting,” he notes. “Handcrafted bronze fixtures and fittings within a garden can add a subtle layer of elegance and quality.” Likewise, sculpture figures into his gardens, in part, because of a fondness for the late Breon O’Casey’s work.

Maynard has a great appreciation for a garden’s “sense of place”—something that develops from careful planning and keen observation. “A sense of place is the soul of the garden,” he says. “It is the intangible and harmonious atmosphere that stems from the perfect balance between the house, garden, landscape, plants, and importantly, the dreams of the owners.”

Creating it, he says, requires patience. No matter the setting—rural or urban—Maynard spends quite a bit of time observing the environment, taking photos, and making sketches. “I must first establish a little history of the existing garden,” he explains. “Many of my ideas are inspired by gardens of the past.”

The designer-client relationship is one Maynard greatly respects. “I think it is important to remain in touch with clients and the projects, as so much [more] knowledge can be gained from watching a garden grow and develop over time.” Maynard believes creating a garden that harmonizes with its landscape can only be achieved by knowing the plot and the area well. Therefore, he observes surrounding fields, houses, and architecture and talks with clients about their intentions for the garden. “They are involved every step of the way, and need to be,” he says. “We want to know throughout the process that we are creating a garden they are going to love and enjoy.” He notes that many clients have gardeners, but when it comes time to set out plants—particularly in a kitchen garden—he invites them to experience the act of planting.

Having started his design business over two decades ago, Maynard has worked with some clients for many years. One such client owns a large country estate in Derbyshire—Haddon Hall. Originally, he designed a garden for the family home, which sits on the property. Today, he is creating terraced gardens around the 12th-century main house. The smaller home once served as a games pavilion for the main estate but the client had updated the interior with contemporary furnishings. “Our design for the garden needed to reflect this shift towards a more contemporary style while retaining the authenticity of the original,” notes Maynard. The solution was to plant a grid of copper beech cubes that give bold structure to the open space. For contrast, he chose a soft planting of herbaceous grasses and flowers. An indented lawn at the center is a subtle repeat of the pattern found in the terrace of the bowling green of the main hall. Against the house stand magnificent scented roses and a deep perennial border. To the back of the house, a naturalized terraced amphitheater sown with a mixture of grasses and species bulbs makes for a dramatic display.

Furthermore, he has taken the house’s history into account in his design, and has re-instated a natural dying garden with plants that would have been used for dying the silks found in the tapestries hanging in the Hall. Additionally, the knot garden features plants that would have been used in the original gardens laid out when the Hall was built. Maynard’s hope is that by referencing these plants and styles in the contemporary design, Haddon Hall gives the impression of being fresh and exciting but always in view of its ancient history. Such is an Arne Maynard garden.

Noted for his incorporation of big broad bands of native grasses and perennial plantings, Maynard also seeks to create habitat for beneficial insects and pollinators. “We always try to include areas of long meadow grass in our designs and leave discrete wild areas of nettles for butterflies and predatory insects,” he explains. He notes the importance of a property’s aspect, climate, soil type, and land contours. “We must be aware of [these things],” he says, but we must also be mindful of the environment itself, and ensure the final design ‘holds hands’ with its landscape both aesthetically and sustainably.”

For inspiration, Maynard turns to the late William Kent whom he credits with creating “a near-perfect garden” in Rousham, Oxfordshire—a classic example of the early landscape movement, remodeled by Kent in the early 18th century—and a place he returns to time and again. “[It’s] proof that the fundamentals of good design don’t change,” notes Maynard, who says Rousham is about simplicity and quality of design. “It is a big, grand garden, but every time I visit, I come away with something new that can be re-interpreted in even the smallest of gardens.” From Rousham he has learned a limited palette of plants can produce a very powerful effect. Two or three species of trees, or 10 varieties of herbaceous plants in a border, can be more effective and elegant than a messy mixture.

On a more fundamental level, Maynard believes a garden has the power to unite people with their environment. “It allows them to appreciate the small wonders of nature,” he says. “A garden provides the opportunity to shine a light on and magnify those wonders. And, of course, gardens have the power to calm, heal, inspire, and enthuse.” TB