Restoration & Renovation

Restoring Howard Van Doren Shaw’s Ragdale House

Project: Ragdale House, Lake Forest, IL

Architect: Johnson Lasky Architects, Chicago, IL; Walker Johnson, FAIA, principal; Meg Kindelin, project manager

General Contractor: Bulley & Andrews, LLC, Chicago, IL

By Katie Bloudoff-Indelicato

After a century of service, even the sturdiest of structures will begin to show their age. The Ragdale House, home to creative souls since its construction in 1898, cried out for a pick-me-up, having seen generations of families and thousands of artists pass through its doors.

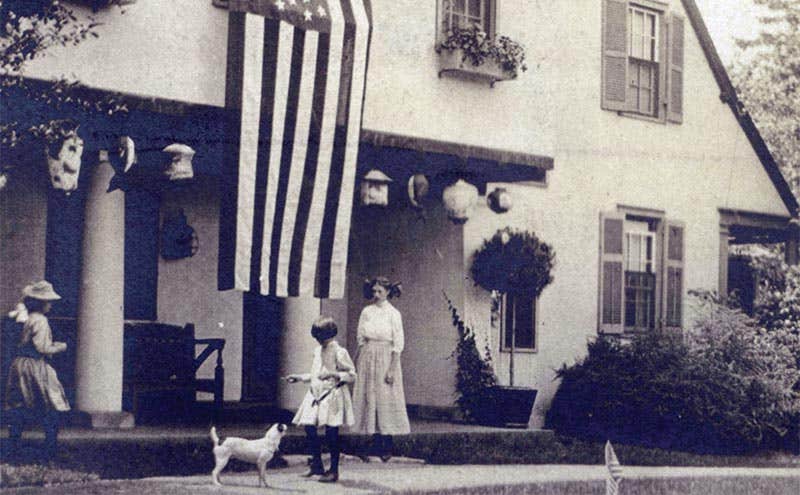

Ragdale was constructed in Lake Forest, IL, by Howard Van Doren Shaw, funded by his parents, and is the culmination of years of work, experience and the melding of European styles. A master of eclectic design, Shaw designed numerous high-end estates, meeting the varied tastes of Chicago’s aristocrats and ultimately earning the AIA Medal of Honor in 1927. He conceived the summer home as an escape from the rigid demands of the day’s upper-class society. Its English Arts and Crafts style was influenced by his 1892 tour of Europe, and softened by his desire to create a simple, country home.

Built by a family of artisans, the site expanded in 1912 with the construction of the Ragdale Ring, an outdoor theater for the production of the family’s plays. Shaw’s wife, a poet and playwright, produced several hits to the delight and amusement of the participating Lake Forest community.

With the passing of Shaw in 1926 and his wife in 1938, the property was divided between Shaw’s three daughters: Evelyn, Sylvia and Theodora. From 1941 to 1948, the three sisters and their families lived on the Ragdale property, making small changes to the grounds and to the house itself. Architect John Lord King made significant changes, including the addition of the McCutcheon home and the conversion of the barn house. Under Sylvia’s possession, the Ragdale House was “winterized” with the installation of thermostats and radiators, and in the 1940s, the oak finishes in the first-floor Arts and Crafts-style rooms were bleached.

Alice Hayes, Sylvia’s daughter, was the next successor to the house. Determined to stave off modernization, Alice maintained Ragdale while preparing for its future as a community for artists. “Alice wanted people to come to Ragdale and do what her family did,” says Meg Kindelin, project manager with Johnson Lasky Architects (JLA), the Chicago-based firm that orchestrated the restoration. “Ragdale was always planned for another kind of life – an artistic life.”

The Ragdale Foundation was created in 1977 to maintain and run Ragdale as an artist’s community. In 1978, Alice donated it to the city of Lake Forest with the intention of running the property as “a place for artists and writers to work,” says JLA principal Walker Johnson.

After Alice died in 2006, it became readily apparent that Ragdale was in need of attention. “It was beyond tired,” says Roland Kulla, an artist and longtime supporter of Ragdale. “Chunks of the foundation had failed, there were a lot of drainage issues, exposed wires, all basic stuff. We all thought that in the near future, we either would have a fire or something and we would lose the house.”

Then JLA entered the picture. Working with the Ragdale Foundation and Bulley & Andrews, the general contractor, the firm developed a plan of action. In 2007, JLA compiled a historic structures report (HSR), documenting the current condition of the house and investigating its origins. The HSR deemed the house to be “in fair to good physical condition overall,” but as construction began, issues were unearthed. “We had prepared a budget for unknowns, but there were a lot of structural unknowns,” says Johnson.

The original foundation, made of brick, had begun to fail and water was leaking into the basement. “The bay addition,” that had been added by Shaw and included a set of dormers above and a kitchen below, “had started to sink and had to be raised three inches,” says Johnson.

“The house originally had cedar roofing and was eventually fitted with a slate roof, which is much heavier, resulting in great sag up in the attic,” says Kindelin. “A good deal of structural work was done, a lot of shoring up with new beams and steel.”

The inside of the house was much of the same: sagging walls, cracked plaster and surfaces that needed refinishing. Thus the challenge began. “Our biggest fear was that the artists would come back and wouldn’t recognize it,” says Kindelin. “We wanted to make sure that when we cleaned it up, the artists would still feel comfortable.”

The goal of the restoration was to enliven the house, not cleanse it. “The house is like an old shoe. It doesn’t demand anything from you. It’s a very comfortable environment,” says Johnson. The peaceful, easygoing demeanor was to be preserved above all else. Step one focused on the exterior and life and safety additions. The structure was stabilized, all exterior walls and the roof were insulated, and fire sprinklers were installed.

Restoration of the windows provided the next hurdle. “Any historic restoration is tough with the windows and doors,” says Kindelin. “Modern, double-paned glass kind of warps your view and really screams modern age.” As the architects wanted to maintain the look of 100-year-old glass, mockups of new windows were created but quickly discarded as unsuitable. The conundrum of the windows and sash continued until Bradley, IL-based Restoration Works devised a solution. “There are 70 different windows. They rebuilt all of the original windows using all the original material, all the same glass,” says Kulla.

“It’s top-notch work,” says Kindelin. “The windows look like they did when the house was first built.”

Turning to the interior, the team consulted historic photographs for the re-creation of three main Arts and Crafts-style rooms: the living room, dining room and entry hall. Research completed for the HSR determined 1926 would be the “restoration target date.” Kulla was in charge of repapering the walls using historic photographs for reference and period-specific paper where more concrete evidence was lacking. Overall there were three main papers for the Arts and Crafts rooms: a morning glory pattern, a lords and ladies pattern and a tree of life pattern.

“We had a wallpaper-stripping party,” says Kulla. “We took off the thermostats in the dining room and found some of the original paper.” After the discovery, the search began to find the manufacturer that had supplied it. Eventually, when searches turned into dead ends, research into the paper provided a surprising, yet logical discovery. “Shaw designed the dining room wallpaper,” says Kulla. “It was a custom job.”

Shaw used Voysey papers for the Arts and Crafts rooms on the main floor. Trustworth Studios, of Plymouth, MA, developed wallpaper that matched. “We managed to re-create that paper and it’s amazing,” says Kindelin. “It’s spot on for this historic interior.”

When it came to the bedrooms upstairs, the style was markedly different. “The second-story spaces showed the popular taste of the day,” says Kindelin, “suggesting maybe his girls had a say [in what their bedrooms looked like].”

“Upstairs we took off the radiators and found more papers that hadn’t been documented yet,” says Kulla, “so we used what we found and other papers.”

“Sometimes we had to be persuaded by the owner to clean certain things up,” says Kindelin. In their efforts to retain the spirit of the house, JLA and Bulley & Andrews carefully assessed the work to be done. “Every move was considered,” says Kindelin. “We wanted to respect the history of the house.”

Donations of furnishings, including numerous pieces of Stickley furniture, brought the house back to its cozy, pre-construction feel. “John Brian, one of the biggest collectors of Arts and Crafts furniture, was one of our biggest contributors,” says Kulla. “He showed up with a truck one day, and we played house, taking our stuff and his stuff and re-imagining things.”

“The house has never looked better,” says Johnson. “With minor maintenance it’s got another 100 years.”

“Overall, I’m very pleased with it,” says Kindelin. “We didn’t restore it and make the house too stiff. We kept the house a living, breathing, older home; it’s not spit and polished at the end. The soul of Ragdale has not been disturbed.”

Katie Bloudoff-Indelicato is a freelance writer based in Northern California.