Restoration & Renovation

Triple Creek Farms: A Restoration and Renewed Life

Project: Triple Creek Farm

Architect: Don McDonald, AIA

In the middle of 200 acres of pastureland outside Fredericksburg, Texas, architect Don McDonald, AIA, saw a building he wasn’t sure what to do with. It was a two-story limestone house with a cistern dating back to the mid-19th century, the last vestige of a homestead in the middle of a remote frontier where skirmishes with the natives had been facts of life. But by the turn of the 21st century, when a family approached McDonald’s San Antonio firm about creating a weekend home, the structure hadn’t been a residence for nearly a century. And after spending its previous 60 years as a hay barn surrounded by plowed fields of grain, it had severely deteriorated. “Before we got to know the building,” McDonald says, “it was debatable whether it was worthy of a serious restoration.”

Then, while cleaning a century’s worth of dust and soot off one of the doors, McDonald and his team uncovered its beautiful faux graining. Then they revealed the classical proportioning expertly rendered on the millwork. Finally, they tore a shed off of the home’s original façade and found the original plaster, scored like stone and painted in pale pink colors that echoed a palette permeating the home—and erasing the idea that this was just another primitive country cottage. “It was only when we started unveiling it that we realized we had this gem of a house buried underneath,” McDonald says.

Today, surrounded by cedar and elm on a low-rise valley hillside near the trio of streams that lend its name, Triple Creek Farm’s nine modern structures are rooted in a regional agrarian architectural response to The Cottage, as McDonald’s team calls it—a core structure built in the 1850s with an 1860s addition. That’s around when highly educated Germans fled religious and political persecution in their homeland to form agrarian communities in Texas based on philosophical ideas, and upon close inspection at Triple Creek Farm, McDonald discovered that The Cottage evinced the same refined sensibilities that had been in vogue in Europe in the mid-19th century and that the immigrants imported.

“If you go back to what [architect Karl Friedrich] Schinkel was doing in Germany at the time, with very sophisticated neoclassical paint palettes, cobalt blues and greens, all of that was transferred here, and it was not transferred in a naïve way,” McDonald says. “As a counterpoint to the pale pink plaster, the delicately milled door panels were painted a robust yellow and outlined with a lime green, all set within a pale grey frame, which really blew us away.”

That degree of refinement compelled McDonald and his team to spend a full year studying the region’s architectural dialect and those neoclassical traditions before starting the project in earnest. To get their bearings, they regularly consulted with the late Gene George, a preservation expert at University of Texas San Antonio. In working on such a small scale—the cottage is 900 square feet on each of its two floors, plus a 12-by-12 wood-clad structure housing baths and laundry that was added by McDonald, and a large, open front porch—the restoration became “more like preserving a piece of furniture than preserving a house,” McDonald says. “We simply protected and preserved everything as we found it as opposed to trying to replace it: pegs that were added awkwardly, or steel straps that were binding pieces of wood together that had been added over the years.”

Ultimately, rather than building a 5,000-square-foot single-family home alongside the restored cottage as first proposed, McDonald says his firm decided to build a “sympathetic” series of smaller buildings—a barn, studio, storage building, exercise and guest room, garage, utility building, and three individual “sister houses” for the family’s three daughters—that played off the cottage and remained faithful to similar landscapes and the agrarian context of the region. “I don’t think the owners were expecting us to come back with a whole series of different structures, but once we discovered how important the original Cottage was, it forced us to move in that direction,” McDonald says.

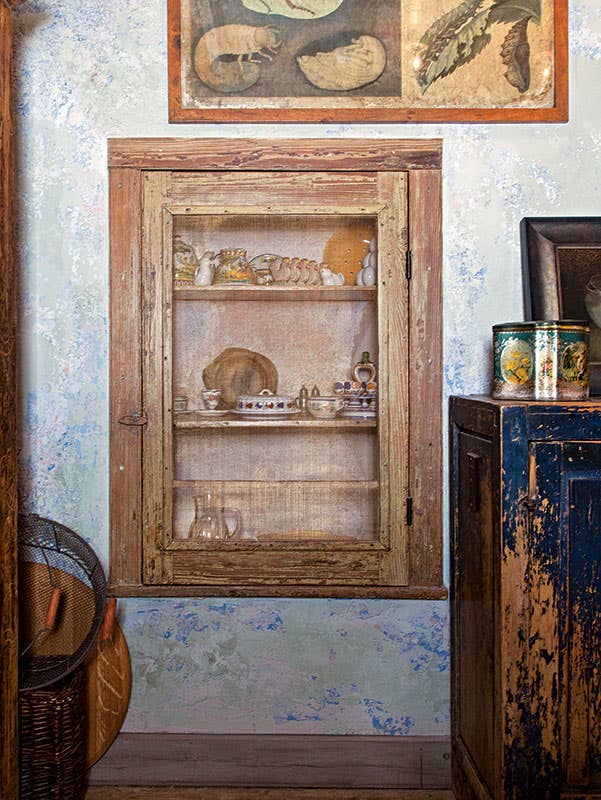

Even now, the small, stoic cottage takes the spotlight. A front porch overlooks the original approach, fieldstone walls, and pedestrian gate, which wind to a façade painted in pale pink, green, yellow, and cobalt blue. Behind a pair of perfectly proportioned front doors, the first floor comprises two rooms—living and dining—with massive, whitewashed plaster walls juxtaposed against confederate grey, mortise and tenon windows; some 150 years after their construction (and a few broken panes notwithstanding), the windows opened and closed like new, letting in and shutting out the prevailing southeast breezes. Similarly, leading to the second floor within the 1860 kitchen addition, the delicate appearance of the stairway belies a hardy mortise and tenon construction that meant every balustrade post and stair tread was pinned together like a single piece of furniture and provided inspiration for a half-dozen new staircases placed around Triple Creek Farm’s new buildings.

With so many details sustained for so many decades, the restoration of The Cottage meant keeping as much of the original structure intact as possible and steering clear of added closets, walls, and other features. McDonald’s firm salvaged and reused the original faux-grained doors and—with the exception of sanding away peeling sections and matching the colors—preserved and sealed the original paints and whitewash. While they updated the home with electricity and strategically placed monopoint light fixtures, they kept the old turn-of-the-20th-century wiring intact and positioned all technology, including electric, audio, video, and air conditioning beneath the original long leaf pine floors rather than within the walls. McDonald’s team also outfitted the roof with Wallaba shingles, resembling the hand-split cypress shingles from the time of The Cottage’s construction. “Throughout the whole project, we were very respectful of keeping the story of the evolution of building fabric intact,” he says.

Structurally, the old stone structure had performed remarkably well, considering there was no foundation and the rubble stonewalls only penetrated the expansive clay soil 20 inches. The masonry structure was reinforced in the traditional fashion with iron tie rods penetrating the walls and spanning the ridge of the roof structure.

And after the restoration of The Cottage, the scale of the other nine buildings (and the pocket gardens nestled in between) drew on the same neoclassical cues filtered through a modern-day lens. “Some people look and think those response buildings are too contemporary, others think they’re too traditional,” McDonald says. “I like that ambiguity, because what we’re trying to do is a 21st-century response to the architectural ideas of that era, as opposed to a museum or a recreation…It’s more about the way they saw beauty, or what was poetic or meaningful to them, and how they expressed that through architecture, as opposed to just an archaic idea that we were trying to replicate.”

Despite all that the restoration of The Cottage at Triple Creek Farm has revealed, an enduring mystery remains: no one knows precisely who first built the home with such lasting expertise. Who would have ventured across an ocean, broken away from the nearest German enclave, traveled deep into the hostile Texas frontier, and brought to life such refined neoclassical details?

The lack of an answer only enriches the backstory of Triple Creek Farm. “That’s what makes it even more intriguing,” McDonald says. “...It’s a rare gem that we came across: a time capsule of European culture dropped very intensely into the middle of Texas.”