Restoration & Renovation

Gary Brewer’s American Foursquare

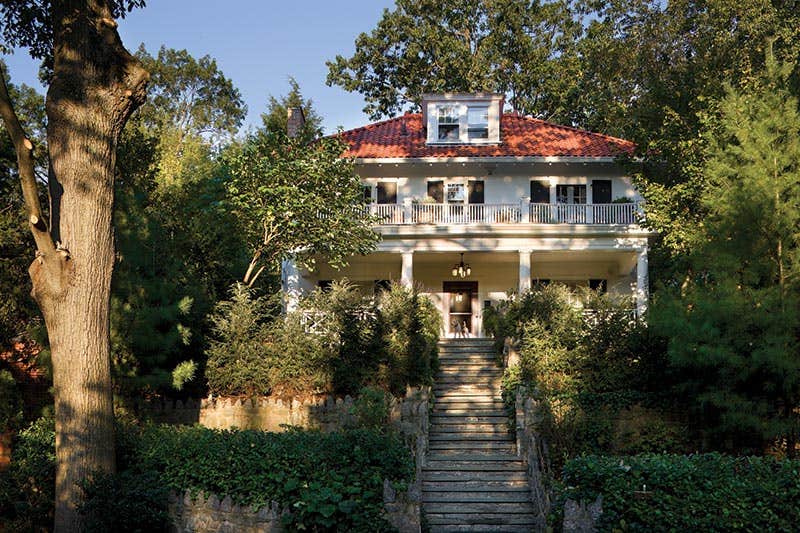

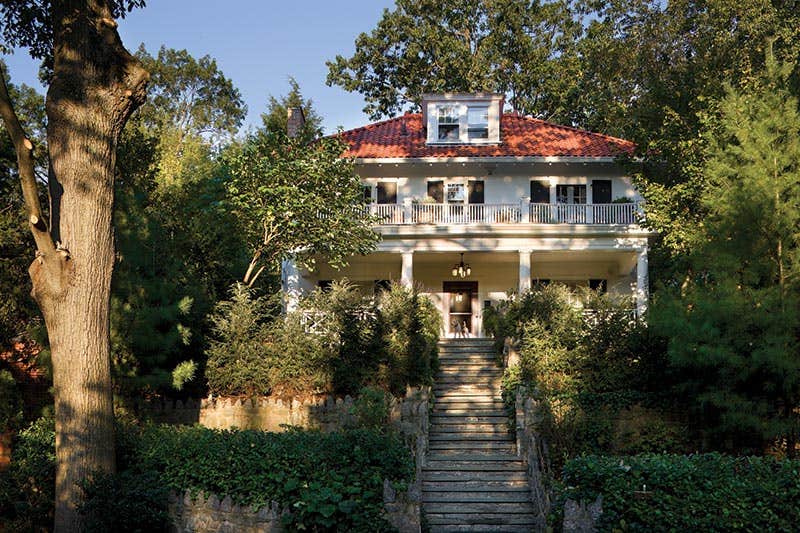

Project: American Foursquare House, Park Hill, Yonkers, NY

Architect: Gary L. Brewer, AIA, New York, NY

After living in New York for 10 years, architect Gary Brewer found himself at a crossroads familiar to many first-time homebuyers: Stay in the city or go further afield? The year was 2003, and Brewer, now a partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects, was architect-in-charge for the Perkins Visitor Center at Wave Hill in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. At the time, Brewer was renting an apartment in Brooklyn’s Carroll Gardens neighborhood and was interested in buying a townhouse. Having spent more than a decade in Greenwich Village and Brooklyn, Yonkers was not on Brewer’s shortlist, until a New York Times article caught his eye.

“I came across the house almost by accident,” he says. “There was an article in the Real Estate section’s ‘Thinking of Living In ...’ column on the Park Hill neighborhood and its history, with pictures of three houses for sale. After a meeting at Wave Hill, I decided to drive to Park Hill and ended up buying the house featured in the article. I had really only driven through Yonkers before and knew little about it.”

Brewer, a partner who joined RAMSA in 1989, has a broad portfolio of university buildings, hospitality and cultural centers, specializing in new traditional design. He has won national acclaim for both his high-end custom residences and pattern book houses such as the 1994 Life magazine Dream House and This Old House magazine’s 1998 Dream House in Wilton, CT. Of the former, more than 7,000 plan sets have been sold, while editorially for one year to educate potential homebuilders and buyers about the design and construction of traditional houses.

Beyond being a place to live, the 1906 two-story American Foursquare house in Park Hill presented something of a research project. The neighborhood was developed by the American Real Estate Company between 1880 and 1930 and was featured in RAMSA’s book, Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City, published by The Monacelli Press. And the house itself was immediately identifiable as an American Foursquare – a common pattern-book house type – owing to the stairs in the middle, porch across the front and hipped roof.

“Having worked on the dream houses and lectured on the history of American pattern-book houses, I knew exactly what it was,” says Brewer. “The house is essentially a box: if you take the square plan and divide it into four, that’s how the rooms lay out. American Foursquares come in various styles, such as Craftsman and Colonial Revival, and were very popular after the elaborate Victorian-era houses because they were easier to build and fit on narrow village lots.”

The house sits high upon a ledge, overlooking Tibbetts Brook Park, and is surrounded by stonework and mature trees that give an exaggerated sense of distance from its neighbors. While it was not completely lacking in detail, there was no clear aesthetic, and like many historical houses, it had been modified over the years with varying degrees of success. Working loosely from the outside in, Brewer’s first tasks were to replace existing concrete walks with bluestone, add more landscaping, and update the porch with new handrails, Chadsworth columns and an AZEK soffit. Not a “do-it-yourselfer,” the architect used multiple contractors to work through his checklist, prioritizing from things he could not bear to live with to minor irritations that could wait.

Inside, the first order of business was to lighten the atmosphere. Changes to the ground-floor entry had resulted in a rather oppressive welcome; the original beams had been removed to accommodate a dropped ceiling, and the casings and wainscot had been shellacked to a dark brown/black. After first sanding down the casings, which took one week, Brewer elected to paint the remainder of the woodwork. “I had a great painter,” says Brewer, “and I used Farrow & Ball paints throughout the house in colors typical of RAMSA houses, which also highlighted the architectural features.”

To the left of the entry hall, the living room was face-lifted with new custom brick tile from Waterworks over the existing dark, dirty-looking exposed brick walls. The dark brown/black original ceiling beams were painted to complement the new, lighter color scheme while a new Brewer-designed wood mantel and over-mantel add detail. “I love Craftsman-style houses if they have a lot of detail,” he says. “I normally tell clients that if their historic house has stained wood, it’s probably better not to paint it, but the oak in my house was really dark, and to bring it back to life would have taken a long time. I wanted a lighter look.”

Opposite the living room, the dining room ceiling had been lowered slightly, so was missing its original beams. New beams were installed to match those in the living room and the entry hall, along with new wainscot, and light fixtures from Rejuvenation. A new custom window replaced the existing small piano window to allow more natural light into the room. In signature RAMSA style, Brewer designed a new built-in buffet in which to store his collection of antique English transfer ware. “People love the period-style built-ins in our houses,” he says, “so I added what might have been appropriate historically to the style of my house.”

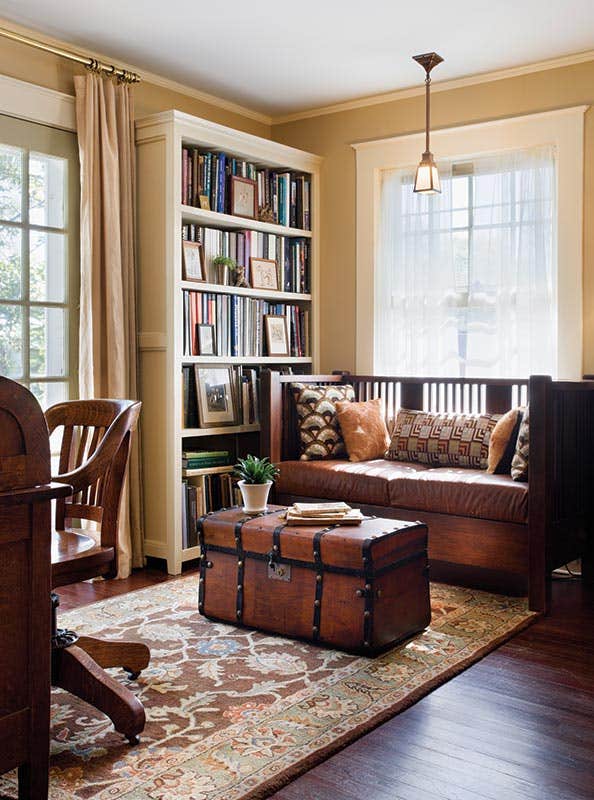

Upstairs, in typical American Foursquare fashion, the second-floor layout originally mirrored the first with four small rooms and no real master bedroom. Brewer removed a wall and moved a door to create a large bedroom with windows on three sides, and French doors that open to the balcony above the entry porch. The remaining two rooms serve as a guest bedroom, with a new built-in closet, and the study, which overlooks the porch and features new bookcases for Brewer’s large collection of books on architecture and interior design. Above, the attic dormer room serves as both a second guest bedroom and a sewing room for Brewer’s partner Barbara Brust, who works in the theater-costuming department at Juilliard.

Brewer drew upon his broad knowledge of the history of interior architecture to be his own interior designer. A long-time frequenter of Chelsea Flea Market and “antiques row” on Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue, his acquisitions generally date from 1830-1910. More important than finishing touches, however, is a solid foundation. “For all the houses we work on in my office, the architects develop the look of the room – the architecture,” says Brewer. “I always feel that’s what the best interiors are about, and that the interior design supports that.”

“I would say that the things I prefer are not eclectic,” he adds. “It’s mostly traditional furniture. I’m also interested in how pre-war middle-class homeowners furnished their houses. As architects we are taught that modernist patron-style houses are important – and a part of me loves Modernist design – but I always think, ‘What would my parents’ generation have wanted in a house?’”

It was proof of a job well done when a visitor exclaimed, “Oh my gosh, you have my grandmother’s dream kitchen!” Here a three-phase renovation banished dark cabinets and orange and brown 1970s wallpaper in favor of a 1940s-style kitchen. The original cabinet boxes were retained, but transformed with white paint, new doors, trim and brackets. New wainscot, casing, an island, and appliances modernized the room – just enough. As storage was at a premium, Brewer designed a built-in pantry and a cabinet for wine glasses. “The kitchen was a complete disaster,” he says, “which was fortunate because a lot of people who looked at the house couldn’t see past that.”

In place of tiny windows, a new door, windows and sidelites by Marvin Windows & Doors open the kitchen’s breakfast bay to the back yard. Stone retaining walls and landscaping provide privacy while the new bluestone patio, breakfast bay and grill spot around the corner provide several options for outdoor dining and coffee.

Upon purchasing the American Foursquare, Brewer was presented with a fascinating record of its history and occupants. “I bought this house through Jane McAfee, a realtor and neighborhood advocate who owns a Victorian house in Park Hill,” he says. “When I moved in, she gave me a record that a long-time resident had collected of every house and who lived in it. I got this handwritten note card that listed all the families who had lived in my house, and there weren’t that many – just eight since 1906.”

“That’s what’s so interesting about houses,” Brewer adds. “Every house has a story, no matter where.” After 10 years, the architect has no plans to add another chapter. “I finally feel like it’s completely done. Now it’s time to enjoy it.”