Restoration & Renovation

Restoring Fair Lane, The Henry Ford Estate

The 1915 house that Henry and Clara Ford built on the Rouge River in Dearborn, Michigan, is an intriguing blend of Midwestern Prairie School and English country manor styles. Measuring 31,000 square feet, Fair Lane is one of the first historic sites to be designated a National Historic Landmark. And it is in the midst of a major renovation.

In the Fords’ day, the 1,300-acre estate comprised a working farm, private garage and laboratory, greenhouse, indoor pool, skating house, bowling alley, pony barn, hydro-electric powerhouse and dam, and staff cottages—all surrounded by grounds designed by landscape architect Jens Jenson.

Upon Clara’s death in 1950—three years after Henry’s—most of the estate’s furnishings were sold at auction. In 1951, the Ford Motor Co. bought the property and used it for offices and archives until 1956, whereupon the Fords’ grandson, Henry Ford II, helped transfer the estate to the University of Michigan to serve as a campus. Ultimately, it was closed to the public due to its deteriorating condition and, in 2013, the University transferred ownership to the newly formed Henry Ford Estate, Inc.—the nonprofit now helming the restoration.

Project Phases

Given the scale of the project, it was broken into phases, the first of which began in 2014 and focused on urgently needed infrastructure repairs; these included redoing the roofs and foundation of both the main house and the 9,000-square-foot powerhouse, as well as rebuilding a retaining wall along the river. Second came the meticulous restoration of the first-floor formal rooms, namely the living room, billiard room, music room, sun porch, library, dining room, and entry foyer; their restoration is set to be completed by the end of this year. Next, they will start populating those rooms with furnishings. The final phase will concentrate on the last of the 57 rooms. “We hope by the end of 2020 to have all of the rooms restored, and about 75 percent of the furnishings done,” says Mark Heppner, vice president for historic resources at Historic Ford Estates.

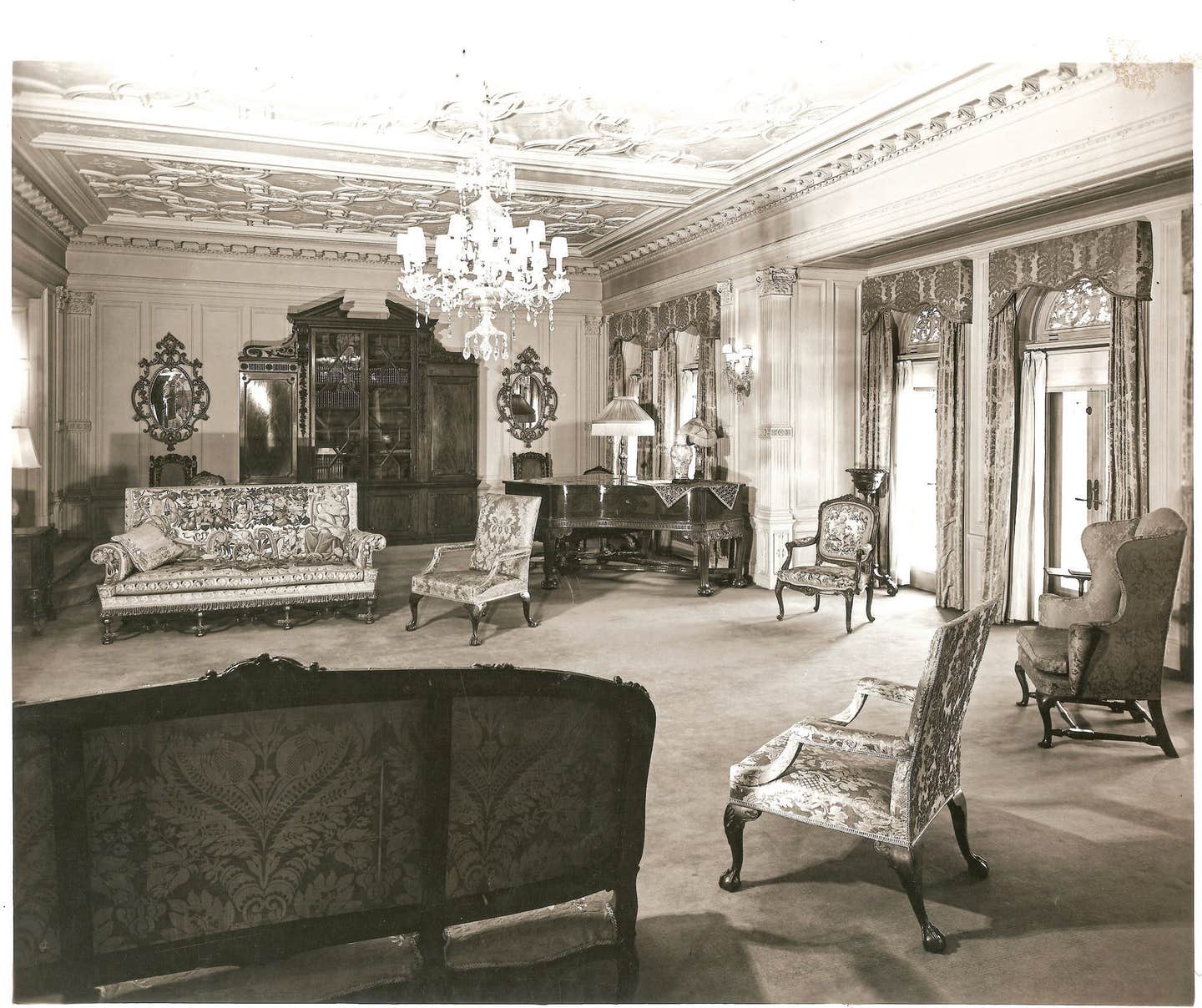

An expert team of historians and artisans is working to remove over 70 years of wear and tear. Then, they’ll create replicas of the original décor. At their disposal are original photographs of each room, receipts for purchases made in 1915, original catalogs, letters, and other correspondence. They also conduct microscopic and chemical analyses to gather as much information about the original rooms and furnishings as possible. “You’d like everything to be an exact science, but none of it is an exact science,” notes Heppner. “At the end of the day, the foundation of everything we are doing is solid scholarly research . . . to paint the clearest picture of what [this home] looked like—the intent, materials, artisan[ship]. But it is never a 100 percent filled-in puzzle.” It is, however, impressively close.

Project Artisans

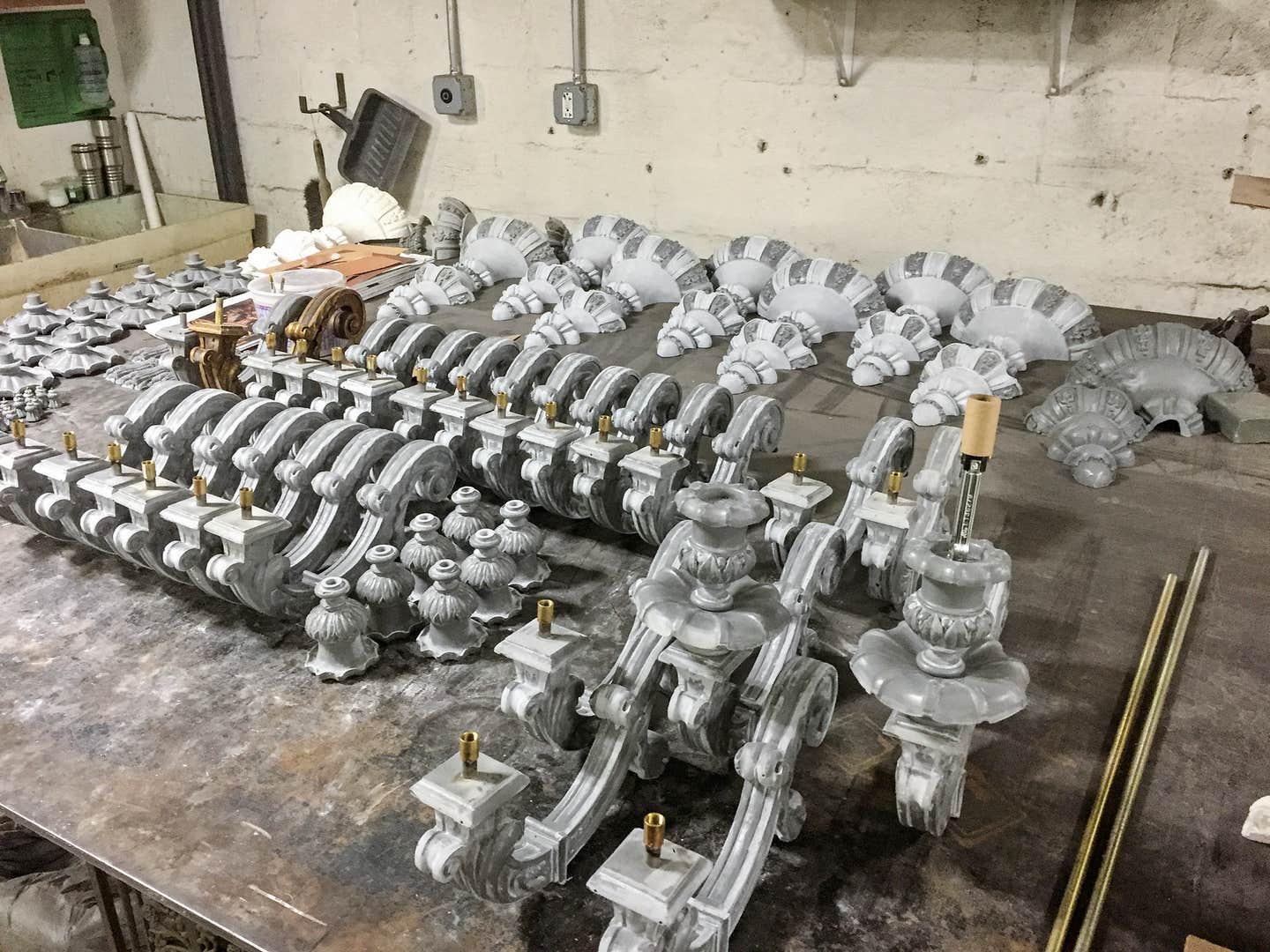

One of the artisans working on the project is Matt White, who, together with his brother Jon, owns Heritage Metalworks, the company charged with the lighting for the library, billiards room, and music room. “They have great archived photos, literature, and documentation showing us a roadmap of what we needed to make,” says Matt. “They were looking to us to interpret what was there.”

Part of their work required “filling in the blanks.” Blurred photographs omitted the refined details that characterized lighting fixtures by Sterling Bronze Co. and Caldwell & Co.—two companies from which many of the original fixtures were purchased. The Whites looked to their archived work, held by the Smithsonian Museum, to make decisions about how to fill in those blanks. Because those photos are black and white, determining finishes was a challenge. They researched metal finishes and fabrication processes of the period, and reviewed purchase receipts from Sterling Bronze Co., which often specified finishes. Additionally, by referencing millwork, molding, plaster work, and other key points in the library, they were able to determine the size of a missing chandelier and scones. It’s this kind of sleuth work that makes the project so demanding and rewarding.

Reconstituting the cold-cast and gilded music room sconces and wrought-iron smoking stands required a mix of techniques. In some cases, the team used 3-D printing to form design plans; other times, hand sculpting was used. Pieces were cast using the lost wax process, which can pick up highly refined details, and is effective for lending a feeling of age.

Restoration Process

Heppner says practicing patience is key to the painstaking restoration process. He also stresses the value of the relationships formed with the tradespeople working on the project. “We are celebrating the arts, crafts, and trades of the past as well as those of the present and the future,” he says, adding that he expects people working on the project to see themselves as invested partners willing to go to extreme lengths to get things right. “They have to be passionate about what they do.”

Forging relationships with the right tradespeople also makes it possible to employ best practices. Heppner cites the example of a hardwood floor restoration expert who uses a passive refinishing technique to remove layers of stain and wax to reveal the original floors, which he then treats with oils used at the time they were laid. “The history and heritage are in the wood floors, and by sanding them you lose all that history, and you are weakening the floor,” Heppner explains, adding that, were it not for that expert input, they surely would have sanded the floors.

He also references an unofficial Brunswick Balke collender billiard table expert who suspected the ornate cabinet that stood flush with the wall in the billiards room would have been recessed in Ford’s time. After tapping around on the wall behind it, he was proven right. It has since been relegated to its original position in the room—adding yet another authentic detail to the house.

When renovations are complete, Fair Lane will frame the Ford family’s story. Visitors will enjoy a house museum experience without boundaries—they will be free to explore all aspects of the home that once meant so much to one of America’s great captains of industry.