Projects

Restoring the Crane Estate’s Italianate Courtyard

Project: The Casino at the Crane Estate

Original Landscape Architect: Arthur Shurcliff

Restoration: The Trustees of Reservations

COST: $3 million

By Jeff Harder

At Castle Hill in Ipswich, Massachusetts, the Grand Allée unfurls like a half-mile-long ribbon of green straight into the cobalt blue of the sea. The allée is a key vista on the property’s 165 historic acres: a hundred-foot-wide column of hills framed by manicured hedgerows and Greek statuary, lending a focused line of sight from the English manor Great House on the top of the hill down to Ipswich Bay. The only interruption is a single stone balustrade sprouting in the middle of the hillside.

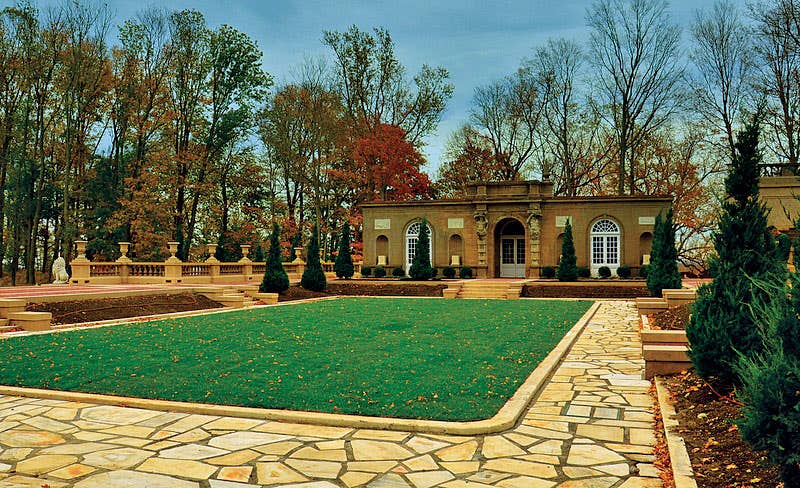

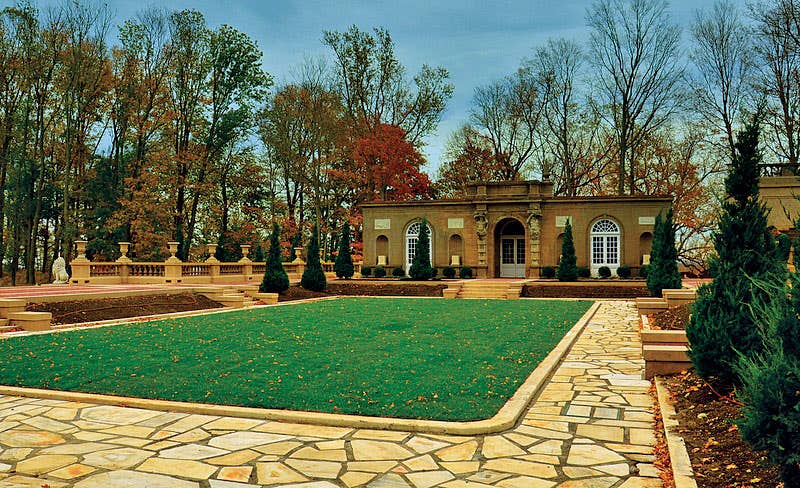

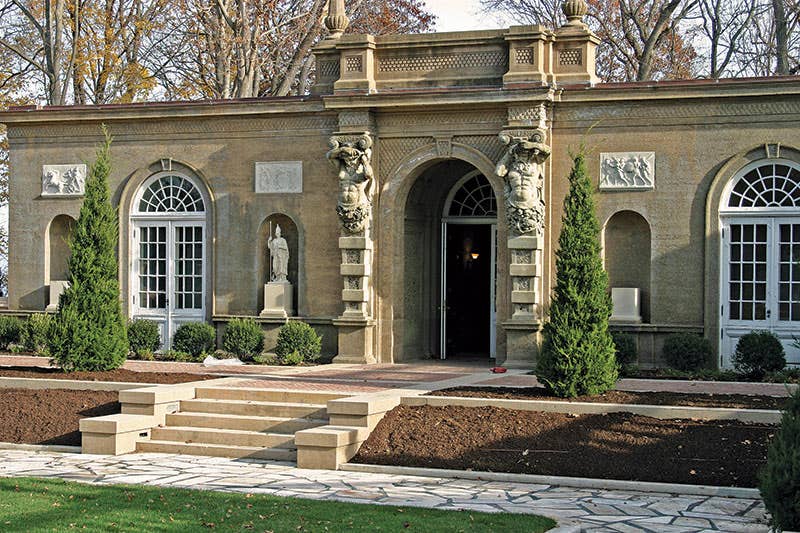

But when you get up close and gaze over the balustrade, you learn there’s a secret down below: the Casino, a 12,000-sq.ft. Italianate courtyard full of ornate architectural details and punctuated with columnar plantings of cedar. “It’s like a home that’s been dropped into the hillside that puts you in an entirely different place,” says Cindy Brockway, program director for cultural resources at The Trustees of Reservations, the preservation group that cares for Castle Hill and 111 other properties in Massachusetts.

A century after its construction, the Casino remains a marvel of Italian Renaissance Revival style as well as a tribute to the extraordinary talents who conjured it. Once a place for a wealthy Chicago family to house and entertain its summer guests, the Casino—which, in this case, means “little house” instead of a gambling establishment—fell prey to 20th century deterioration. But now, after a roughly $3 million restoration that materialized over nearly 20 years, the Casino is set to welcome summer visitors of a different sort.

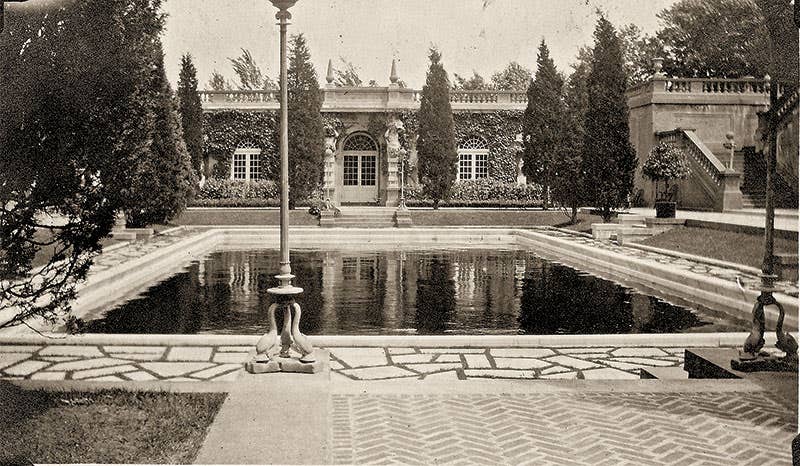

After a long tenure as a farmland, Castle Hill’s most recent incarnation began in 1910, when Chicago industrialist Richard T. Crane, Jr., bought the property to serve as his family’s summer estate. The designed landscape adapted tenets of Italian Renaissance Revival design to coastal New England, complete with a villa overlooking the property. (Mrs. Crane’s lasting umbrage with the villa prompted its 1920s transformation into the Great House, the 59-room Stuart-style home that exists today.) The Cranes planned to place a saltwater pool in a valley between two hills, a measure that threatened the view. But Arthur Shurcliff—a neighbor, who also happened to be one of the finest landscape architects of his day—proposed a compromise: cut into the hillside, terrace the pool, and only a stone balustrade would remain.

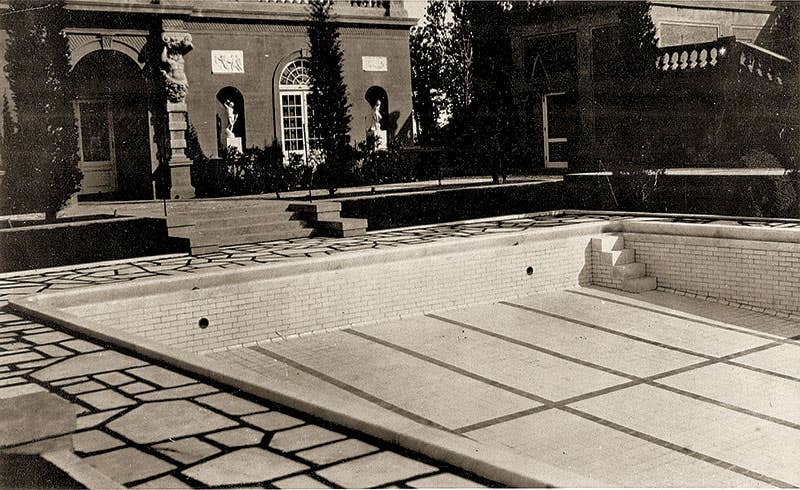

The results, carried out by Shurcliff as well as the Boston architectural firm Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge, were the Grand Allée and the Casino, a complex containing a courtyard, ballroom, and bachelors’ quarters, and a place where guests could lounge in the sun away from the Great House looming up high. “It’s a space that really reflects the Italian Renaissance Revival in its highly articulated architectural details, its design, and its decorative elements,” says Bob Murray, The Trustees’ operations manager who helped oversee the restoration of the Crane Estate's Italianate Courtyard. “It brings out some of the incredible detail that was so typical of this era, and it creates a much different experience as you enter this more intimate space.”

Today, the Casino looks almost indistinguishable from its century-old forerunner. On either side of the balustrade in the middle of the allée, staircases descend alongside a 15-ft.-high concrete retaining wall into a space rendered in exquisite detail, with a number of smaller changes in elevation. Brick laid in a herringbone pattern encircles the courtyard, and six sets of stairs descend 2 ft. further to a jigsaw of marble pavers surrounding a lawn panel. (The Cranes filled in the pool back in the 1940s.) The ballroom and the bachelors’ quarters were born of the day’s etiquette, which barred raucous young men from the main residence—adorning the buildings’ entryways with term figures that depict Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and merrymaking, wasn’t an accidental choice. Eight classical-style statues cast from late-19th-century molds fill niches in the buildings’ façades, and a second balustrade caps a lower retaining wall on the north side of the courtyard.

It’s a long way from the Casino’s former state of disrepair. Shortly after the Crane family donated Castle Hill to The Trustees in 1949, the Casino began to deteriorate: the weather took a toll, a leaky tar-and-gravel roof on one of the buildings collapsed, and a particularly insidious problem called alkali-silica reaction caused the concrete in the retaining wall to deteriorate from the inside out. “Concrete is made of sand, water, and aggregate, and the voids in between hold it together,” says Jim Younger, The Trustees’ director of structural resources and technology, who oversaw some of the restoration on the Casino’s concrete features. “Essentially, those voids formed a gel over time that became bigger than the voids themselves, causing breaks and fractures that eventually became a powder in the wall.” By the 1990s, the Casino was in such bad shape it had to be closed to the public.

But after Castle Hill became a National Historic Landmark in 1998, attention turned to bringing the Casino complex back to its former glory. The buildings were repaired and the concrete retaining walls were faithfully reconstructed to their original dimensions. Work on the terrace had to wait, but in the meantime, The Trustees carefully removed and stockpiled the original marble pavers, coping, and balustrade, then filled in the courtyard with a lawn. After beginning the restoration of the Grand Allée in 2007, bringing back the Casino courtyard became an aim of the project. In April 2014, crews began excavating the area, removing earth and exposing the courtyard’s original footings and foundations, pouring new slabs and foundations, and laying irrigation, wrapping up the project the following autumn.

Along the way, the landscape stayed true to Arthur Shurcliff’s early vision, while casting an eye toward sustainability and lower maintenance plantings. Beyond the vertical cedars, the Casino features a hearty groundcover composed of vinca, candytuft, geraniums, and other perennials, along with ferns in shadier spots and a layer of inkberry bushes in front of the buildings. “It’s remained more of a classical, green, Italian space, and it’s very understated when it comes to the plant choices,” Brockway says.

With the restoration complete, the upshot is simple: the Casino is ready to welcome guests once again. Along with a slate of programming in the works for the coming summer, the Casino complex will include seating, refreshments, and games—including a billiard table in the ballroom, just as there was a long time ago—to make it an anytime destination.

And ultimately, the Casino—amidst the vastness of Castle Hill—is a place that naturally lends itself to visitors, Brockway says. “You’re completely enveloped by this little world, and instead of looking out, all of the sudden, you’re looking inward.”