Period Architecture Topics

Reinterpreting Palladio’s Villa Rotonda

Nearly 500 years ago, Andrea Palladio designed the Villa Rotonda. Since then, it has become the most iconic of Neoclassical houses. There are four versions of the Rotonda in Great Britain. In America, Thomas Jefferson designed two unbuilt versions of the Rotonda, including a competition entry for the White House in Washington, DC.

The newest American Rotonda is located in the historic district of Gates Mills, OH, which was part of the Western Reserve of Connecticut in the early 1800s. I designed the house in collaboration with my wife, Janer Danforth Belson, a Classical archaeologist by training, who wanted a family home with a distinctive history of its own. Between excavations in Greece and research in Italy, we visited most of the Palladian villas in the Veneto. Many featured a multi-generational live/work environment, which we embraced as part of our program of requirements. We noted that Palladio used modest wall materials such as stucco on brick, rather than marble, for his villas. Palladio featured these villas in the Quattro Libri, which became a pattern book for 18th- and 19th-century American house builders, including those in Ohio.

Challenges

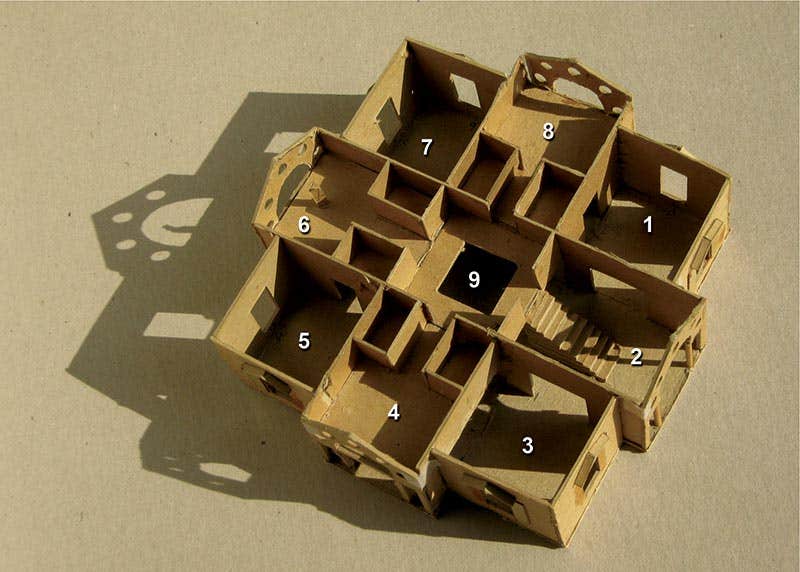

Conceptually, the Villa Rotonda was the source of inspiration for the design of the floor plan, the cross section and the massing of the new house. The primary design challenge was to create a multi-level functional floor plan within a bold geometrical framework that would be flexible for a modern family.

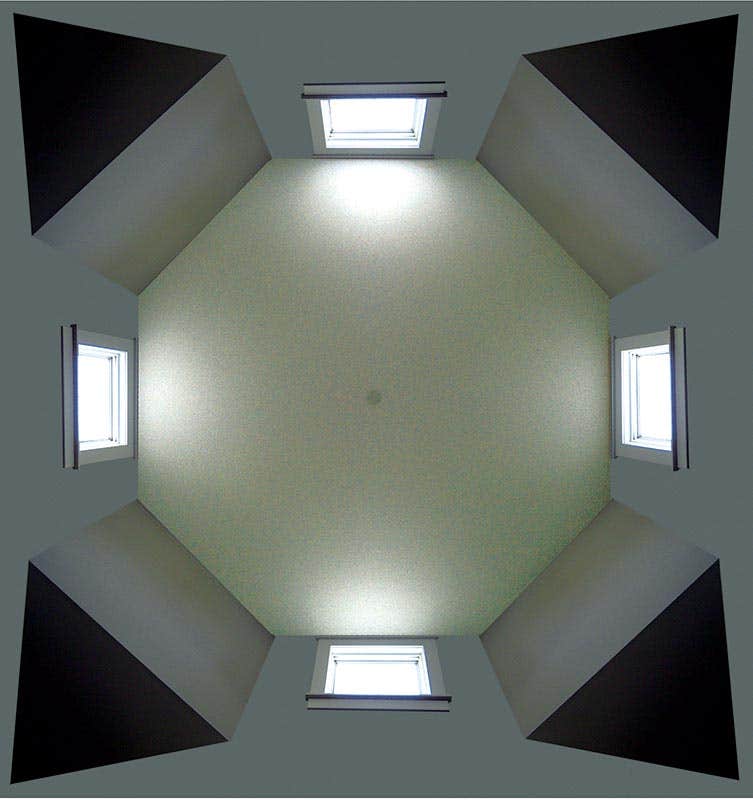

The southeast elevation of the new house shows a central tower surrounded by a square block, whose boundaries are defined by the four corner chimneys. The five oculi over the entrance to the house recall Palladio’s use of the Serliana motif at the Villa Pojana and elsewhere. The octagonal tower in the center of the house is similar in cross section to Palladio’s restoration drawing for the Baptistery of Constantine, although in the new house, triangular pendentives are used to transition from a square to an octagon.

Windows and doors of similar size are placed enfilade at floor level and line up with smaller clerestory windows above. This creates light-filled rooms with 14-ft. ceilings in each of the four corners of the house, including the living room, as well as the first-floor dining room, family room and master bedroom. The corner fireplaces in these rooms create a dynamic interior focus.

The building plan shows three second-floor bedrooms tucked under the gables. These three rooms have the look and feel of the grain storage rooms that Palladio located under the gables of Pojana. The basement level contains a large office for a family consulting business.

The seamless integration of art and architecture is important in the design of Neoclassical structures. For instance, the Medusa appears on many Classical buildings as an apotropaic device to ward off evil spirits. Our Medusa was salvaged from an early-20th-century Beaux Arts building in New York City that was recently demolished. This “beautiful type” Medusa is similar to the famous “Medusa Rondanini” located in the Glyptothek Museum in Munich. Based on my wife’s publications, the original Medusa Rondanini is now generally thought to be an example of 2nd-century Hellenistic sculpture, rather than 5th-century Classical sculpture. In ways like this, the more important paintings, sculpture and furnishings in our house each have their own unique story to tell.

Details

Locating the chimneys in a house with a central tower is problematic, both visually and functionally. Palladio would agree, because in the Quattro Libri he simply omitted showing the actual chimneys on the elevations of the Villa Rotonda. Chimneys would be obtrusive distractions in an otherwise idealized elevation drawing. Most watercolor renderings of the Villa Rotonda similarly omit the chimneys.

Moving the chimneys to the four corners of our house, as far as possible from the tower, improved functionality by increasing the draft within the flues. It also made the chimneys an important part of the overall composition of the exterior elevation. Current building codes would require that Palladio’s chimneys at the Villa Rotonda be extended to become almost as tall as the tower itself. There are a number of details we designed for the placement of chimneys, windows, clerestory windows, doors and even handrails that have allowed us to create inventive variations on Palladio’s original theme.

Materials

Traditional materials used for historic houses in Gates Mills and for the new house were also very modest. These natural materials include cedar roof shingles, copper flashings, masonry chimneys, painted wood clapboard as well as tongue and groove wood siding and trim, half round gutters with full round downspouts, and operable cedar shutters.

As far as practicable, materials were locally sourced. The oak floors throughout the major rooms of the house were custom milled by Amish craftsmen in nearby Burton, OH, from select Appalachian hardwoods. Cleveland-based manufacturer Sherwin-Williams supplied exterior paint, and environmentally-friendly low-VOC interior paints and floor coatings. For the shutters, a Sherwin-Williams color appropriately called “Gates Mills Green” was selected.

Based on the LEED protocol of the U.S. Green Building Council, the source of most non-local materials was limited to within a 500-mile radius of the site. The Vermont slate for the bathroom floors and the Vermont soapstone for the kitchen and bathroom countertops were shipped from a supplier not far from Bennington, which is 500 miles away.

The compact, highly efficient plan of the new house maximizes floor area and minimizes exterior wall and roof area. Super-insulated walls, a low ratio of glass to wall area, as well as a geothermal system, result in an average HVAC energy consumption of 10,000 BTU/SF per year. This is 50 percent less than the average for a new house in the U.S.

Reaction

Not long after we moved in, a car pulled up and an elderly gentleman with a cane stepped out, saying, “Sorry to bother you, but my wife and I wanted to ask if the five circles over the door were borrowed from the Villa Pojana.” That was not what I was expecting. Like the elderly gentleman and his wife, the reaction from many people has been surprisingly positive and informed. They perceive that there is a very powerful geometry to the house. They understand that this geometry equally serves both aesthetic principles and functional requirements. Some say that the idealized plan looks both highly formal and highly flexible, and that they like the combination. Calder Loth, of the Center for Palladian Studies in America, visited not long ago, and said afterward:

“As you (and Jefferson and others) have discovered, Palladio’s villas are quite adaptable for new interpretations. I wish more people would accept the challenge. Interestingly, unlike Britain, America does not have a good adaptation of the Villa Rotonda. Monticello does not quite do it and Jefferson’s two more pure designs for a Rotonda house were never built. I think your house is the closest we have come to one.”

Charles Belson is president of Belson Design Architects and president elect of AIA Cleveland. He is vice president of the Cleveland Circle of the Decorative Arts Trust. Belson’s work as an architect has received an Honor Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a number of Merit Awards from the AIA, and LEED Gold and LEED Silver certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. He received a B.A. with honors in the history of art from Yale, and a masters in architecture from Harvard.