Features

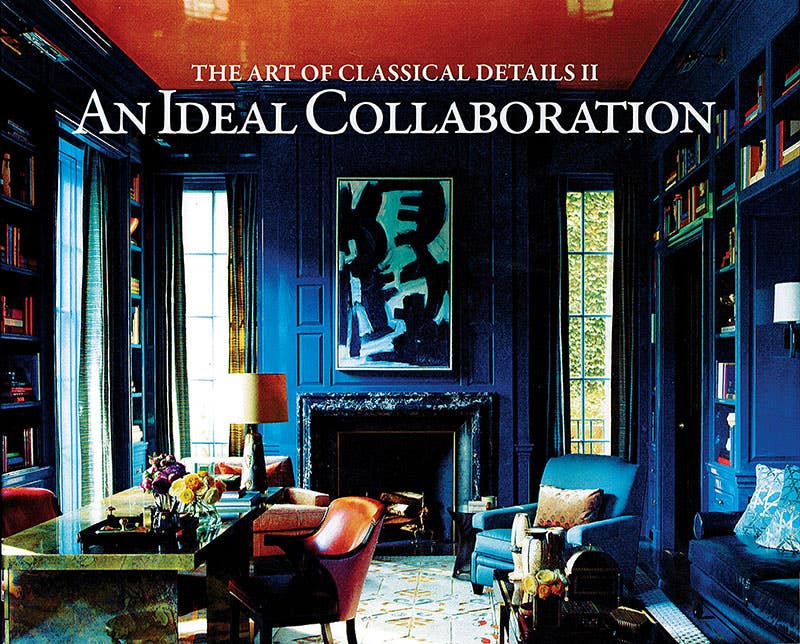

The Art of Classical Details II: An Ideal Collaboration

By Phillip James Dodd

Published by Images Publishing, 2015

Hardcover; 300 pages; $70, ISBN: 978-1864706017

Reviewed by Alvin Holm

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Throughout history the process of design and construction has been well known to involve the close collaboration of many talents from many fields sometimes over very long periods of time. In an era where the "Starchitect" still reigns, where the idea of the lonely genius still captivates the public mind and holds sway within the schools, this handsome volume is a welcome antidote.

Throughout history the process of design and construction has been well known to involve the close collaboration of many talents from many fields sometimes over very long periods of time. Geniuses abound and often receive just credit for their great buildings, but the army of artisans and brilliant craftsman working in concert all along were well known to be co-creators. This book focuses on contemporary practice and personal testimony rather than recounting the tradition, and that is well and good. Far too frequently lessons from the past are easily dismissed as “that was then, this is now.”

The subtitle of this book is The Art of Classical Details II, and although it can very well stand on its own considerable merits, it is clearly designed as a companion volume to the first The Art of Classical Details: History, Design and Craftsmanship. They both are organized in such a way that they are good for browsing, beautiful illustrations alternating with winsome writing, and equally good for serious study. Notable in my experience of both books is a sense of cheerfulness throughout. This quality is achieved by lively layouts, lavish photos of all sizes, from explanatory vignettes to two-page panoramas, and consistently upbeat essays. The mood is set by an exuberant forward written by the Interior Designer Ellie Cullman, who refers to this volume as a “testimonial to the mutual respect we support and maintain in this close-knit, highly spirited, and very collaborative business of design.”

The 16 essays by a wide variety of professionals are all valuable, coming as they do from very different points of view to reinforce the overall theme. As an architect myself, I was especially interested in “A Builders Perspective” by Palm Beach Contractor John Rogers. He notes that “Collaborate is a term frequently used, but an act seldom performed. Nowadays it is constantly offered in sales and marketing materials…. Yet true collaborative relationships are in reality very rare, as sharing does not often come naturally to many designers.” Alas, I think he is right about that. But Rogers argues very effectively that “an early involvement of the whole team (Architect, Decorator, Consultant, and Builder) lends itself to a better understanding and appreciation of each others’ role in the project.” And shared goals are essential.

Architect Kahlil Hamady’s essay “A Visit to the Mount” is notable for addressing a broad range of historical and literary sources relevant to the central theme, including an extensive discussion of Edith Wharton’s wonderful book The Decoration of Houses written in 1897 with architect Ogden Codman Jr. I hope Hamady’s reference to Wharton will encourage readers to seek out that book. Those who do may be as profoundly affected as I was when Henry Hope Reed persuaded me to read it 40 years ago.

One of the most personal and engaging of these essays is written by Francis Terry, the architect son of the renowned English Architect Quinlan Terry. He writes of his youth when he was “torn between wanting to be an artist and an architect, a common dilemma which has faced many artistic students.” His reason for ultimately choosing architecture “goes right to the heart of the nature of collaboration.” His story is a delight to read, and he closes with this comparison: “Painting is, of course, one of the highest and most intense art forms, but it is small and personal… Architecture, on the other hand, paints on a far broader canvas, which requires the collaboration of many differently skilled people in its execution, and this is, in essence, the joy of architecture.”

Another essay especially illuminating because of its autobiographical nature is John Milner’s on “Design and Preservation.” As one of the first of his generation to devote a private practice to preservation, he is able to tell us of his discoveries and how he learned a great deal about traditional building that had not been taught in schools since the Second World War. “Putting myself in the mind of the craftsman,” he writes, “allows me to make a direct connection between concept and execution.” And Milner concludes with: “The most rewarding projects with the best results are those that have had the benefit of collegial and collaborative relationships among clients, designers, builders and craftsmen. Design is the first step, but the craftsmen’s contributions are fundamental to realizing, enriching and giving personality to a final creation.”

The final essay, by William Bates III, is “The Academic Experiment.” To my mind it is possibly the most inspirational of all. He swiftly summarizes the radical shift in the arts and education that took place in the wake of the Second World War. “Postwar modernists promoting all things traditional as obsolete, if not heretical, seized on the decline of craft to support their grip on the architecture of America.” Eloquently, Bates recounts the struggle to get things back on track, including the efforts of Henry Hope Reed and the growth of the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. Finally, in the fall of 2005, the new American College of the Building Arts was ready to accept its first incoming class. For many of us, this new institution is one of the strongest indications that a “New American Renaissance” is underway.

While the excellent essays of the first half of this fine new book make the case as well as words can do, it is the projects illustrated in the latter half that prove to our eyes that all will indeed be well in the years to come. It is this book by Phillip James Dodd and its earlier companion volume that are both agents and evidence of that New American Renaissance.

Alvin Holm, AIA, is an early advocate of traditional design, in private practice since 1976, and winner of the first annual Clem Labine Award. He has lectured and taught widely, having initiated a course in Design with the Classical Orders in the National Academy of Design in 1981 and subsequently at many other institutions. He has been an ardent member of ICAA since its inception and prior to that, an officer in Classical America.