Period Architecture Topics

Charles Rennie Mackintosh: The Father of “Glasgow Style” Creations

"There is hope in honest error, none in the icy perfection of the mere stylist." – J.D. Sedding

The city of Glasgow on Scotland's west coast is renowned for its industrial heritage, feats of science and engineering, and its contributions to culture and art. From John Logie Baird, inventor of television, to economist Adam Smith, and numerous actors, writers and poets, Glaswegians' mark on the world is profound. But few match the legacy of architect, artist and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the father of "Glasgow Style."

"He was one of the most creative architect/designers working at the turn of the last century," says Pamela Robertson, senior curator and professor of Mackintosh Studies at Glasgow University's Hunterian Museum. "In common with many of his contemporaries he believed that the architect was responsible not just for the fabric of a building, but for every detail of its interior design. He was one of the most sophisticated exponents of the theory of the room as a work of art, and created highly distinctive furniture of great formal sophistication. His achievements continue to inspire today."

Mackintosh was born in the Townhead area of Glasgow on June 7th, 1868, the fourth of William Mackintosh and Margaret Rennie's 11 children. Playground taunts over his limp and drooped right eyelid caused him to seek solace in the countryside, where he developed a lifelong love of landscapes and flora. Mackintosh was, however, a product of his city. He lived in Glasgow for most of his life, where the River Clyde – its gateway to the world – exposed him to the trappings of the Industrial Revolution, mass production, and the art and culture of a globalizing Far East.

At age 15, Mackintosh enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA), regarded then and since as one of the most prestigious academies in Europe. Under headmaster Francis Newberry, who brought with him from London a keen interest in William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement, the school had recently departed from pure fine arts education to embrace a range of crafts, including pottery, textiles, metalwork and stained glass. Mackintosh continued to take evening classes while pursuing a career in architecture, first with an apprenticeship for local architect, John Hutchison, before transferring in 1889 to the larger firm of Honeyman and Keppie.

As a student, Mackintosh accumulated an impressive roster of prizes and accolades, including the second Alexander Thomson Traveling Studentship for Public Design in 1890. Committed to "furtherance of the study of ancient classic architecture," the award's 60 pounds funded Mackintosh's seminal architectural tour of Italy, Antwerp and Paris. Surviving sketchbooks demonstrate the young architect's increasing maturity, which primed him for Glasgow's late-19th-century peak in reputation for architecture and design.

Upon his return, Mackintosh resumed his position at Honeyman and Keppie by day and his studies at GSA by night. Together with fellow GSA students Margaret McDonald (whom he married in 1900), her sister Frances, and Herbert MacNair, he formed "The Four," a group of artistic visionaries whose unique take on Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau earned the moniker "Glasgow Style." With Newberry's support, the group debuted an exhibition of metalwork, posters and furniture at the 1896 Arts & Crafts Exhibition in London, showcasing Glasgow Style's blend of Celtic imagery and abstract motifs, the most enduring of which was a cabbage-like flower, the "Glasgow rose."

By the exhibition, Mackintosh had several important commissions under his belt and an increasingly strong design aesthetic. His commercial work at Honeyman and Keppie included an office building for the Glasgow newspaper The Herald (1894), Martyr's Public School (1895) and a new building for his beloved Glasgow School of Art (1896). Considered his masterwork, the latter's two phases integrated Scotland's early Baronial style with the looming 20th century's materials and technologies. Mackintosh's fusion of influences defied clear association with prevailing trends. His admiration for the simplicity, textures and forms of traditional Japanese residential design, and Arts & Crafts architects such as J.D. Sedding, was at odds with the emerging Modernist movement's definition of the home as "a machine for living." And though less ornamental than the Victorian style, his integration of Art Nouveau and Scottish themes rejected the extremes of raw industrialism.

Mackintosh's view of the home as a work of art, for and by the individual, drew wide acclaim in continental Europe. In Austria, he contributed to the eighth Vienna Secession, an exhibition of young artists and architects, and he also held exhibitions in Germany, Turin and Moscow.

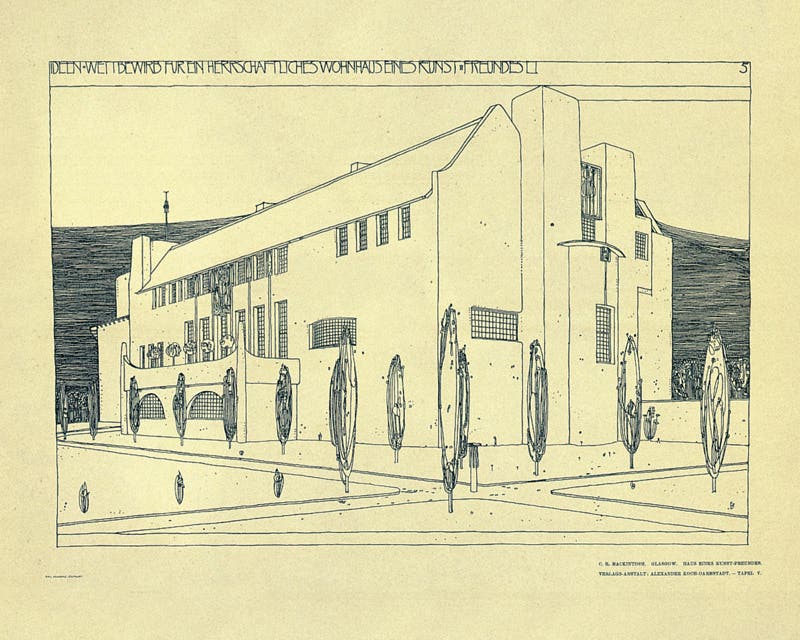

A House for an Art Lover

In 1900, Mackintosh entered German design journal Zeitschrift for Innendekoration's 1900 competition to design "A House for an Art Lover." Though disqualified for late submission of some interior drawings, German architect Hermann Muthesius said of the design, "The exterior character of the building exhibits an absolutely original character unlike anything else known. In it we shall not find a trace of the conventional forms of architecture to which the artist, as far as his present intentions were concerned, was quite indifferent."

"A House for an Art Lover" remained but a few sheets of paper until 1989, when civil engineer Graham Roxburgh decided to turn Mackintosh's ideas into reality. An assembled team of architects, designers, builders and craftsmen, led by Andy MacMillan, the Head of Architecture at GSA, referenced Mackintosh's completed buildings to flesh out the technical details of his sketches. The building opened in Glasgow's Bellahouston Park in 1996 and retains strong ties with the GSA as a center for the visual arts.

Hill House

Mackintosh's most celebrated commission, Hill House (1904), owes much to "A House for an Art Lover" and an earlier residential commission, Windyhill (1900). Publisher Walter Blackie commissioned Mackintosh to design not only the house and grounds, but also the furniture, fittings and decorative schemes. The architect's wife, Margaret, designed and produced many of the textiles, as well as a "sleeping princess" gesso fireplace panel. Allegedly, Mackintosh advised the Blackies on which flowers to place in the living room, to avoid clashes with the décor.

Situated high above the River Clyde, in the Helensburgh area of Glasgow, Hill House's simple form is a mix of Arts and Crafts, Scottish Baronial and Japonisme. Its light-filled rooms take advantage of the site's expansive views and have undergone a faithful restoration by the National Trust for Scotland. Mackintosh's signature "Glasgow rose," strong vertical lines and cut-out squares feature in every room, which vary in tone from the dark, masculine library to Margaret's silk hangings and elongated female forms in the main bedroom.

Despite his popularity in continental Europe, Mackintosh's holistic approach to design had a limiting effect on his career at home. Few private patrons in Glasgow had the financial means to commission his "total packages," yet he was notoriously unwilling to compromise.

One notable exception was temperance advocate Catherine Cranston, who commissioned Mackintosh to design and furnish a series of tea rooms, from their high-backed chairs, light fittings and wall decorations down to their cutlery. The most famous, the Willow Tearooms (1903) at 217 Sauchiehall Street, was at the center of the movement to entice the working class away from "the demon drink" and reopened following a full restoration in 1983.

Mackintosh resigned, despondent, from Honeyman and Keppie in 1914 and moved to London with Margaret at the onset of the First World War. He continued to work on interior commissions, and experiment with bold, geometric textiles, before hanging up his architect's hat forever with a move to the South of France in 1923. There he returned to his love of landscapes, and spent the last years of his life painting watercolors.

More than a century since the peak of his career, Charles Rennie Mackintosh remains a considerable influence on the city of Glasgow and on architecture and design at large. The Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, an independent non-profit charity, was formed in 1973 to promote awareness of his life and works through lectures and tours. In addition to several private collections, the largest single holding of his work is found at Glasgow University's Hunterian Museum, as is The Mackintosh House – the reassembled interiors from his Glasgow home.

Mackintosh died on December 10, 1928, having met his own artistic standard. "Art is the flower. Life is the Green Leaf. Let every artist strive to make his flower a beautiful living thing, something that will convince the world that there may be, there are, things more precious, more beautiful – more lasting than life itself." – C.R.M., 1902