Period Architecture Topics

Clem Labine’s Victorian-era Brownstone Renovation

Editor emeritus and founder of Period Homes, Traditional Building and Old House Journal, Clem Labine's Victorian-era brownstone renovation invites us back to 1883 Brooklyn, NY, where it all began.

By LJ Lindhurst

When Period Homes founder Clem Labine bought his Victorian-era Brooklyn brownstone in 1967, the surrounding Park Slope neighborhood was far from its current state. "The neighbors thought I was crazy when they found out I had spent $25,000 on the place," says Labine. At the time, the neighborhood's landmark row houses had fallen into disrepair, and Park Slope was in flux. "There were bars all along nearby Seventh Avenue," he says. "We'd routinely wake up around midnight to a punch-up that had spilled into the street."

The house was built in 1883, and – like many of the homes in the area – had once been a grand four-floor family mansion. Sold in 1930, its rooms had been haphazardly sectioned off to form a rooming house. Kitchens and common bathrooms had been installed, walls erected, and much of the original wood detailing had been painted over or removed. The building had been poorly maintained, and every room needed a full overhaul.

Labine, a chemical engineer, was no expert in renovation at the time. "My first idea was to turn the place into a castle," he says. "I started out small, but as the projects progressed, I found a lot of the original details began to emerge. One day I realized the building was talking to me, and I needed to stop fighting it." It was then that Labine's restoration – and subsequent education – began in earnest. And he wasn't alone: Everett Ortner, the founder of the Brownstone Revival movement, lived up the street, and helped guide Labine and many others who were doing the same with these once-magnificent buildings.

On the basement level, which now serves as the family room, much of the original handcrafted walnut woodwork had been removed. Labine hired local woodworkers to replicate the few remaining strips around the perimeter, above floor-to-ceiling custom-built bookcases. After stripping away layers of paint, Labine discovered that the original Italianate marble mantel in the middle of this room had been carved from the cheapest un-veined marble, and originally finished with wood graining. Using faux marbre techniques, Jersey City, NJ-based Rambusch artisan Helmut Burcherl gave the mantel the appearance of a more elegant, colorful Italian marble with complex veining.

The stairway to the parlor level features walnut wainscoting with a hand-stenciled border that is period appropriate. But as Clem notes, it was once "an unremarkable plaster wall. To create a warmer feeling, I just matched the wood and style of the wainscot on the parlor floor and continued it down to the basement level."

Inside the foyer remains one of the few original ceiling medallions, which Labine restored and refitted with an antique stained-glass lighting fixture. Using the foyer medallion as a model, Labine had ornamental painting artisans camouflage any cheap, unadorned replacement medallions throughout the house.

Other feats of ornamental decoration abound. In the dining area, Labine had a local silkscreen artist create a blue-and-yellow sunflower border, inspired by the Aesthetic movement of the late 1800s, in which sunflowers and peacocks are ubiquitous symbols. On the subject of peacocks, that Victorian-era symbol is well represented in the parlor sitting room.

"I wanted this to be a true sitting room; the kind of room where you formally receive visitors," says Labine. In addition to Victorian-era paintings and furniture, the front-facing room features a large hand-painted Peacock border, the pattern for which Labine found in the Dover Book of Art Nouveau. As no computers or scanning technology were available at the time, Bucherl used an old-fashioned pounce-pattern stencil technique that utilizes small holes and charcoal dust to place the design onto the wall. The pattern was then painstakingly hand painted using gold leaf for the accents. This motif is also used – to dramatic effect – in place of a ceiling medallion in the center of the room. "There was no design for that," says Labine. "I just had Bucherl improvise and match it to the border."

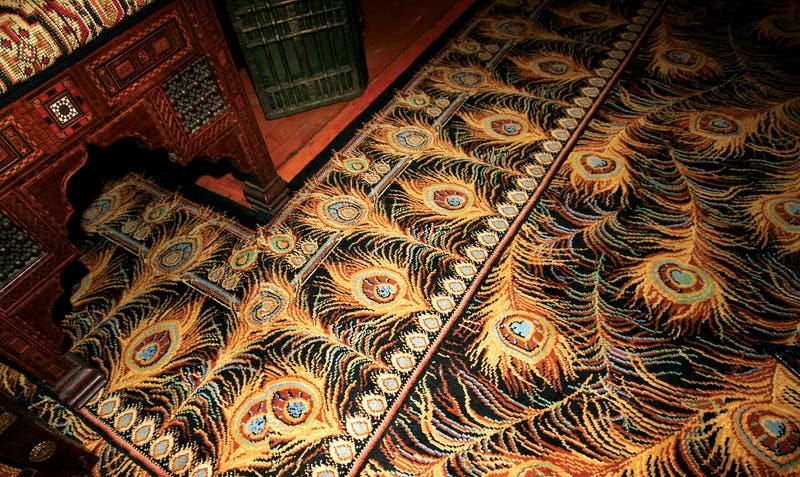

Stained glass, sculpture, and even an imposing stuffed peacock are scattered throughout the room. "A good game to play in this room is to see how many peacocks you can count!" says Labine. (Guests often report blurred vision after twenty.) The narrow-loom carpet, which was custom made for the shape of the room, also features a dizzying peacock feather motif. It was woven to original 1880s manufacturing specifications, which a friend of Labine's discovered at a carpet manufacturer in England.

On the second floor, the master bedroom suite now serves as a guest room. Bookcases line the walls, with a reprise of the custom wainscoting and above-cabinet lighting style found on the basement level. The border and recessed ceiling are ornamented with Victorian-style Bradbury & Bradbury wallpapers.

While much of the restoration can be attributed to hard work, much credit is also due to patience and simple happenstance. "A fellow up the street was gutting his brownstone, and was going to throw this in the garbage," says Labine, referring to the restored mahogany mantel in the parlor. "I asked him if we could make a deal for it."

Unfortunately, only a small number of homes restored during the Brownstone Revival have maintained their Victorian character. "It's a shame," says Labine. "New people move in, and a lot of them want 'Brooklyn Modern.' Why buy a Victorian home if you are going to strip it of its character? Why not buy a loft, or recent construction?"

After almost 50 years, the renovation continues – a wall in the basement was recently found to have termites, and is in the process of being rebuilt. Labine takes it in stride; "It's always something with these old houses. If you care about the place, you are never truly finished."