Features

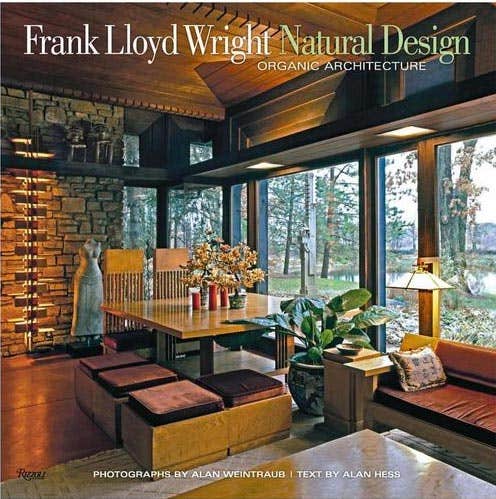

Frank Lloyd Wright: Natural Design, Organic Architecture

Frank Lloyd Wright: Natural Design, Organic Architecture

by Alan Hess; photographs by Alan Weintraub

Rizzoli International Publications,

New York, NY; 2012

223 pages; hardcover; $55

ISBN: 978-0-8478-3796-0

Beside his visionary designs, architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) was famed for his eccentricity and unwillingness to mince words. He had little respect for popular culture (“TV is chewing gum for the eyes.”), the formal education system (“Harvard takes perfectly good plums as students and turns them into prunes.”), government (“Bureaucrats: They are dead at 30 and buried at 60.”), and sacred cows (“The Lincoln Memorial is related to the toga and the civilization that wore it.”).

But behind the cynicism, Wright was, first and foremost, a farm boy from rural Wisconsin whose reverence for the natural world bordered on the spiritual. His belief that natural resources should be used to best advantage, with minimal waste and intrusion on the landscape informed every aspect of his designs, from the use of sunlight, passive heating temperature control and organic materials to site sensitivity. And as a pioneer of what would become the modern “green building” movement, Wright exceeded his own standards by decades: “The architect must be a prophet… a prophet in the true sense of the term… if he can’t see at least ten years ahead, don’t call him an architect.”

Wright’s lessons on sustainability are beautifully presented in the new Frank Lloyd Wright: Natural Design, Organic Architecture. Over seven chapters, photographer Alan Weintraub and architecture critic Alan Hess explore Wright’s most holistic designs, and the philosophies and techniques that find renewed significance today. Projects are grouped by distinguishing features, building types or ideas, such as “Eaves,” “Trellises,” “Hemicycles,” or “Sun Control.” As such, longtime fans of Wright may find new angles on even his most widely discussed buildings, such as Robie House, Price Tower, Taliesin and Fallingwater.

The latter’s leaking roofs, sagging eaves and astronomical costs for upkeep have long been the departure point for discussion of Wright’s near misses and outright failures. However, the authors encourage a forgiving approach to an architect who pushed boundaries – his own and the profession’s in general. While Wright’s experiment with dead-air ceilings at the Unitarian Meeting House in Madison, WI, did not work, for example, the authors point out that his radiant heating system did, and continues to do so. Similarly, comfort is relative: Wright designed at a time when wearing a sweater indoors or escaping to a vacation home for the winter were routine, and not problems that architects were called upon to solve.

In his customary style, Wright broke his own rules on occasion, leading one associate to remark that, “We should not idolize Wright. His buildings did not always live up to his own ideals, let alone our idealizations of him. Neither should we hold him to his own edicts; though he proclaimed buildings should be of, not on, a hill, a number of his buildings sit squarely atop them, such as the Pauson House (1939) and Marin County Civic Center (1957). He proclaimed that a building should be designed for a specific site, but he often designed one house for Wisconsin, and later offered the same design to a client in Arizona. He frequently worked more intuitively than logically.” The author is in agreement, but suggests that logic alone would not have produced the folio of ideas presented here.

Wright died a dozen years before the energy crisis hit, and was just 12 years old when Edison invented the light bulb. As a Modernist, he did not fear or ignore new technologies, but he refused to trade ancient, tried and true ideas for what he termed “dire artificiality.” He instead embraced the future in ways that did not willingly disrupt the balance of nature. Though the results were imperfect, his lessons endure, and are a stark rebuke to the notion that “green” must be an aesthetic or even a debate.