Period Architecture Topics

The American Tradition of Georgian Architecture

Classical decoration and superb craftsmanship guided by elegant proportion form the story of three landmark houses on the coastline of northern New England. Each building tells the tale of rich and powerful merchants, shipbuilders, and maritime adventurers who left behind an enduring architectural legacy. This fashionable Georgian architecture prevailed in 18th-century America since the original thirteen colonies looked to Britain for standards of beauty.

What is Georgian Architecture?

“Georgian” is a term referring to over a century of a design aesthetic, developed during the reigns of Kings George I, II, and III, which looked to the traditions of Greece and Rome and the work of Italian Renaissance architects, the foremost being Andrea Palladio, whose works were popularized in illustrated pattern books and disseminated throughout England and its burgeoning empire. A taste for the classical predominated in this period with variations from the exuberance of Rococo curves in the mid-1700s to the delicacy and restraint of Neo-Classicism at the end of the century. In the course of interpreting English models, however, the “colonials” created something distinctly their own: Georgian architecture.

The Moffatt-Ladd House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the Jeremiah Lee Mansion in Marblehead, Massachusetts, and the Hamilton House in South Berwick, Maine, are landmarks to a truly American spirit in design and may justly be called the “Three Graces” of Georgian architecture in New England.

The Moffatt-Ladd House (c. 1763)

Rising high on a hill above the Piscataqua River, the Moffatt-Ladd House (c. 1763) dominates the waterway that brought untold wealth to Portsmouth. Lumber made its way from the forests of New Hampshire to supply the busy shipyards of the town, while fishing fleets left the harbor for the rich banks off the coast. Among the most successful of Portsmouth’s merchant grandees was John Moffatt, who made a fortune in trade and speculation during the mid to late 18th century. His hopes for the future rested on his only surviving son, Samuel, for whom he built a grand mansion as a wedding present. The house possesses the essential elements of Georgian architecture: a two story cubic form with a main façade of windows symmetrically arranged at either side of a centrally placed door framed by an entrance porch of classical columns topped with a superbly carved triangular pediment. Symmetry and order reigned supreme in this masterful composition.

Any English baronet, squire or merchant would have been pleased with the façade of Jeremiah Lee’s house, which faithfully followed its British Georgian models. Once inside, however, the freedom and ingenuity of American craftsmen are apparent. The Moffatt-Ladd House is a fusion of English architectural sources and American innovation as expressed in one of the most unique stair halls of Colonial New England. The usual Georgian house plan consisted of rooms at either side of a central hall with a staircase at one end receiving lavish decorative attention.

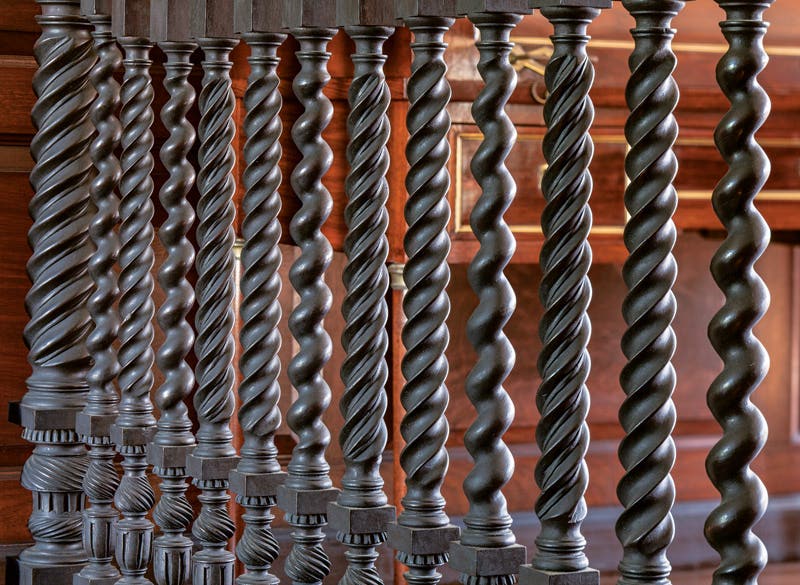

Samuel Moffatt’s staircase is one of the most singular and exceptional masterworks of its age. In this case, the visitor enters a great hall, which takes up one-quarter of the entire floor space, providing a generous view of the sweeping staircase presented as a major sculptural element with a railing of spiral, urn and fluted column-shaped balusters and steps adorned with scrolled brackets.

The balusters of the Moffatt-Ladd stairs create a dynamic rhythm of alternating shapes, a truly remarkable display of the carver’s art. Rising for a few steps, the stairs break at a landing, above that is a magnificent Palladian window framed by fluted Corinthian style half columns. The effect is pure drama for a hall that became the backdrop for the opulent entertainments of one of Portsmouth’s leading families. Today, the house continues to be shaded by the horse chestnut tree planted in 1776 by William Whipple, Joseph Moffat’s son-in-law, after his return from Philadelphia after signing the Declaration of Independence. It is an appropriately lofty image for a place steeped in history.

Jeremiah Lee House (1768)

While the Moffatt’s enjoyed the splendor of their new house, an even grander example of Georgian architecture appeared in 1768 in nearby Marblehead. As one of the richest merchants and ship-owners in the colony of Massachusetts, Colonel Jeremiah Lee spent lavishly on his mansion. Proudly sited in the heart of town, Lee created a three story structure topped by a cupola. The façade is similar to Plate 11 in Robert Morris’s Rural Architecture, published in London in 1750, with the central section breaking forward and topped by a grand pediment. In keeping with English building practices, the façade should have been made of masonry, but the scarcity of such materials in the colonies resulted in wood siding shaped and painted to simulate stone.

The exterior is marked by the disciplined solidity and rectilinear form of wood blocks and window frames, while the interior is an exuberant display of richly detailed carving in sinuous swirling patterns. Complimenting the woodwork is some of the finest wallpaper of the Georgian era still in its original location, which appears in the two-story stairwell and the first-floor great chamber, also known as the State Dining Room or Banquet Hall.

The mid-18th century English paper is composed of hand-painted scenes of Roman ruins in grey tones on 21 by 27-inch sheets set in panels framed by curving Rococo style borders. Inspired by excavations at the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the late 1740s, views of temples, urns, and sculpture became a dominant theme in design.

In the first floor great chamber, originally painted mustard yellow, the fireplace mantel is carved in high relief with garlands and swags resembling the work of the English architects illustrated in popular pattern books, especially Abraham Swann’s British Architect (1745) and James Gibbs’ Rules for Drawing (1728). Thus, Jeremiah Lee was at the forefront of fashion with the architectural details and fine wallpapers for his house.

Unfortunately, he did not enjoy his creation for long. An ardent patriot for the Revolutionary cause, Lee fell ill during the early days of conflict in 1777. His wife, Martha, continued to live in the mansion, which still remained the finest house in town when George Washington visited Marblehead in 1789 during his inaugural tour of New England. The Moffats and Lees made their luxurious houses the centerpieces of bustling seaports.

Hamilton House

Jonathan Hamilton, a merchant and privateer grown rich during the Revolution, opted for a country seat on the banks of the Salmon Falls River in South Berwick, Maine. Here his fine residence sat on a bluff at a bend in the waterway overlooking his wharves and warehouses.

Nature and architecture are in complete harmony in this ensemble. The house appeared like a beacon from every vantage point in the luxuriant landscape of the river. An austere tone prevails at Hamilton House. There are no grand columns, elaborate pediments or intricate carving. Nobility is attained through fine proportions and the perfect handling of architectural forms. The square house is topped by a steeply pitched hipped roof and soaring chimneys. Large Palladian windows, appearing on both the front and rear facades, appear over the main entrances, lending a graceful note to the otherwise unadorned facades. The central hall, with its staircase framed by a simple classical arch, affords a view of the river and forests beyond.

After Hamilton’s death in 1802, the estate passed through a series of owners and eventually fell into disrepair. Taken by the romantic atmosphere of the decaying house on the gentle riverbank, the South Berwick native, Sarah Orne Jewett, took up the cause of its rehabilitation.

She convinced her friend, Emily Tyson, to purchase the house in 1898. Jewett had attained national renown for the publication of The Country of the Pointed Furs (1896), which used the setting and people of the Piscataqua River as inspiration for her writing. Concerned that the artistic heritage and folkways of Maine were quickly disappearing in an industrial age, Jewett advocated for the preservation of historic buildings, rural landscapes, and local crafts.

With a railroad fortune at their disposal, Emily Tyson and her stepdaughter, Elise, were able to enthusiastically embrace the task of restoring the Georgian architecture of Hamilton House. Following the Centennial celebrations of 1876, the Colonial Revival movement was in full force and the Tysons efforts at Hamilton House is one of the most poignant expressions of a romantic fascination with the nation’s past that combined both fact and fantasy.

The main building was restored and new wings sensitively adapted to the original structure. One of the major discoveries was a sample of 18th-century wallpaper in the stair hall, which was reproduced in 1900. Between 1905 and 1907, the Tysons engaged the painter George Porter Fernald to produce wall murals in the main first-floor chambers. In the dining parlor, he created an Italian themed landscape with ancient Roman ruins, Renaissance villas, grottoes, and waterfalls.

The drawing room features his most inventive work, where he created a very American interpretation of the early 19th-century French paper “Les Monuments de Paris” by the renowned French artist, Joseph Dufour. Instead of Parisian scenes, Fernald’s mural depicts the great sites of southern Maine and New Hampshire, including the Piscataqua River, the Lady Pepperell House, the mills of Dover, the Governor Wentworth Mansion, the Sarah Orne Jewett House and, last but not least, Hamilton House. The artist produced a mythic, historic, epic landscape based on local sites, a Colonial Revival tour de force capturing the spirit behind the rehabilitation of Hamilton House. As a fitting tribute to the allure of Hamilton House, Sarah Orne Jewett used the house as the setting for her historical romance novel, The Tory Lover (1901).

Georgian Architecture at the Turn of the Century

The aesthetic appeal and cultural significance that drew the Tysons to Hamilton House was part of the larger public fascination for the Colonial era and its artistic heritage. Across the country, historic houses were being saved and restored as both private homes or public museums. Along the eastern seaboard, 18th-century buildings were of special interest and the subject of a major work of documentation.

At the height of the Depression, in 1933, the Architect’s Emergency Committee produced the publication entitled Great Georgian Houses of America, funded by a long list of financial sponsors. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, President of the United States, appeared at the very top of the list. Architects created floor plans and façade drawings of 77 houses in a two-volume work that raised awareness of these historic sites and the importance of their preservation. The Moffatt-Ladd House, the Jeremiah Lee Mansion, and Hamilton House featured prominently in the New England section. Architectural Historian Fiske Kimball wrote in the the introductory essay to Volume II: “We shall find our houses…to be full of interesting regional variety, characteristic, not merely of America, but of the soil and culture of their own colonies and districts.”

Built on the mercantile prowess and commercial success of colonial merchants, inspired by the classical principles of Georgian architecture, constructed by the hands of superbly talented American craftsmen, and saved and mythologized by later generations of writers, artists and preservationists, the Georgian houses of coastal New England are the stuff of legend, landmarks to architectural achievement and the very essence of grace.

Note: The Moffatt-Ladd House, the Jeremiah Lee Mansion, and Hamilton House are all designated National Historic Landmarks and operated as museums open to the public. The Moffatt-Ladd House is owned by the National Society of the Colonial Dames of New Hampshire. The Jeremiah Lee Mansion is owned by the Marblehead Museum and Historical Society. Hamilton House is a property of Historic New England.

John Tschirch is an architectural historian, writer and teacher specializing in the architectural and social evolution of historic houses and landscapes.