Features

Inventing the New American House: Howard Van Doren Shaw

Howard Van Doren Shaw, an architect who has had a large impact on American architectural design, gets a well-deserved large-format book for readers to savor his work. Stuart Cohen has delivered just that in his latest book, Inventing the New American House: Howard Van Doren Shaw, Architect.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Inventing the New American House: Howard Van Doren Shaw, Architect

By Stuart Cohen

Photos captions and credits: All Images, Courtesy The Monacelli Press

The Monacelli Press 2015

$65 ISBN: 978-1-58093-420-6

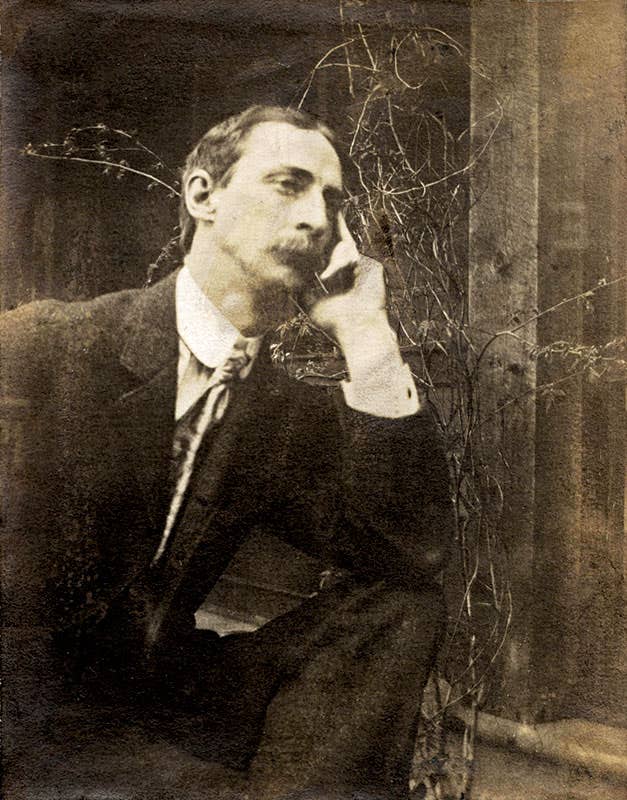

Howard Van Doren Shaw (1869-1926) is revered by today’s new traditional architects for his work at the turn of the 20th century. He adapted classical designs rooted in English and Italian antecedents and embraced the Arts and Crafts movement resulting in eclectic, well-crafted homes for America’s rising industrial and intellectual elite. Numerous collaborations with Rose Standish Nichols and Jens Jensen assured beautiful landscapes that framed his designs as “garden extensions” of the house. Like many of his peers, Shaw’s work defied definition in a singular architectural style. Nevertheless, Shaw’s practiced use of architectural vocabulary demonstrated that good design can be created from taking the best forms from historical precedents and combining them to delight owners and their families and guests alike.

This book is a valuable source of inspiration for today’s contemporary traditionalists. Architects, builders, and designers will benefit from having this book on their book shelf. Architectural historians and those with an avocational interest in good architectural design would do well to acquire it because Cohen does a great job of documenting the historical context of Shaw’s work: the rapid rise of wealth and culture made possible by America’s industrial expansion in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The book features 30 properties in 30 chapters, along with a brief biography, a detailed bibliography, a chronological list of Shaw’s projects, and a reprint of Frances Wells Shaw’s homage to her husband and his work, “Concerning Howard Shaw in His Home.” Each chapter features historic photos that have been carefully reproduced to maximize our understanding of how Shaw used architectural details to convey the achievements of his clients while providing them delightful and functional homes. Most feature contemporary color images of extant properties and many include floor plans, elevations, and garden designs for today’s practitioners to examine. Cohen has scoured libraries and museums for Shaw’s plans to aid readers in their efforts for further study.

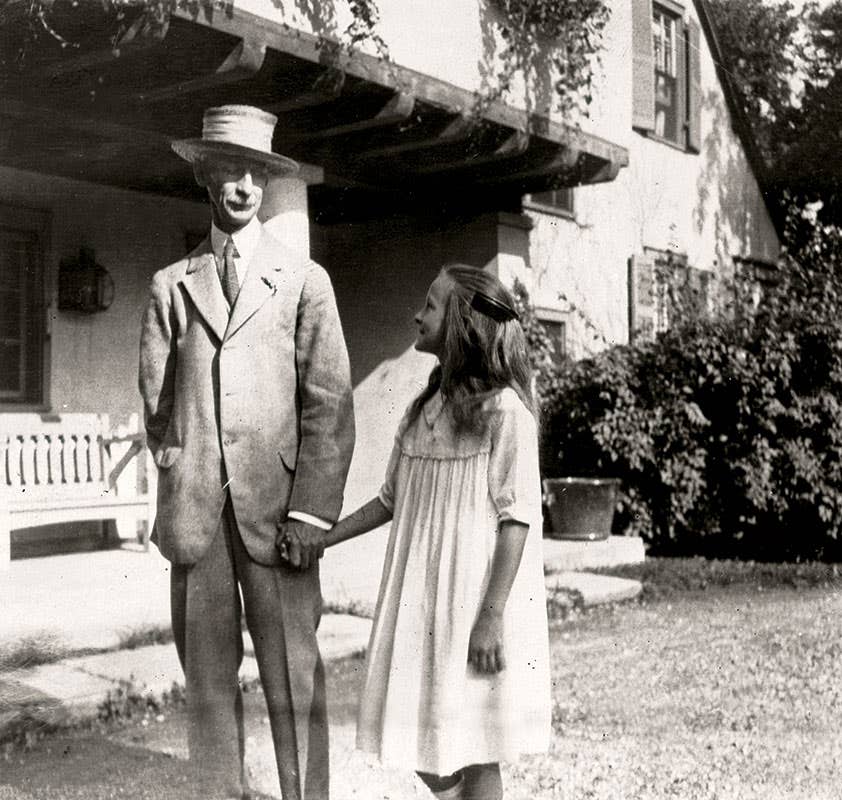

Shaw demonstrated beauty in his buildings, landscapes and craft details. Taking a fresh look at his work today, is a great point of departure for contemporary traditionalists seeking inspiration for their design work and to find ways to best serve their clients. The man who put out milk and cookies for Santa and built an inglenook in his own home so his wife could read to their children while he worked nearby at his desk, gave his clients the same gifts of spaces inside and out of the house to make “joie de vivre” really possible.

It is possible to read each case study on its own and return to each without feeling compelled to read the book from cover to cover. Let’s consider, for example, the House of the Four Winds built in 1908 for Hugh Johnston McBirney, an executive for a white lead company that later became the National Lead Company. The house is only one room deep and features porches on the east, west, and south elevations to capture breezes for cross ventilation during the summer. Shaw employed the use of steel beams to support a chimney without blocking an important view. He worked with Rose Standish Nichols to design a garden on axis with the home. The details of the house and a garden are borrowed liberally from the Alhambra, visited by Shaw in 1892, and from his Prairie School contemporaries. Cohen says it is not “eclectic” but “inventive” in its use of “traditional residential forms.” As such, it exemplifies Shaw’s work.

Shaw was widely recognized by architectural critics and the popular press during his lifetime. Herbert Croly, editor of the Architectural Record, wrote about Shaw regularly. Cohen has chosen to emphasize Croly’s praise from a 1913 article. “Mr. Shaw’s houses possess to a very considerable extent the merit of being thoroughly livable...These houses are charming and inviting to a degree rarely exceeded in American domestic architecture—a fact which justifies Mr. Shaw’s success as well as accounts for it.”

A few days before his untimely death at age 57 in 1926 from pernicious anemia, he became the nineth architect to receive a Gold Medal of Honor from the American Institute of Architects. The upheaval of the middle of the 20th centuries that occurred in rapid succession after Shaw’s death—the stock market crash, the Great Depression, World War II, and a shift to Modernism in architectural design— combined to minimize the memory of Shaw’s great architectural achievements.

The author, himself a practicing architect, educator and Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, has written a fine architectural history as only a colleague and kindred spirit could do. Stuart Cohen’s book will go a long way to make sure that one of America’s greatest designers will be remembered and emulated.