Features

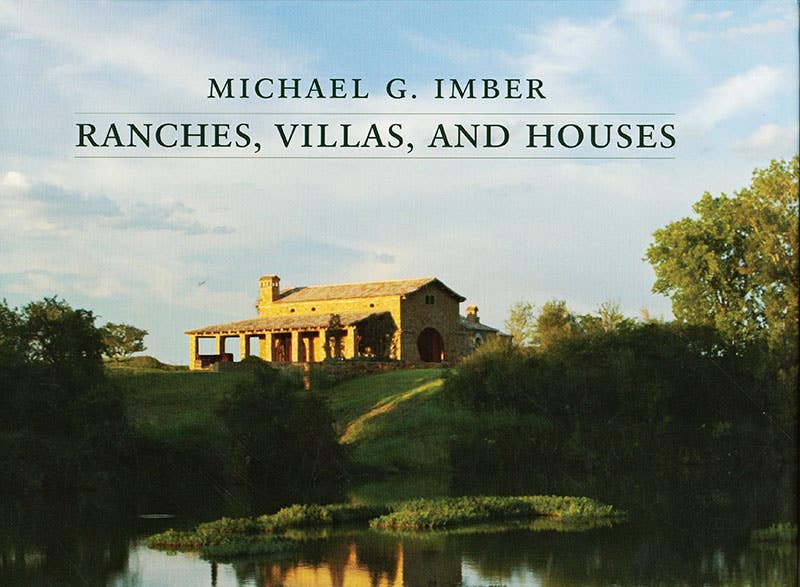

Michael G. Imber: Ranches, Villas, and Houses

Michael G. Imber: Ranches, Villas, and Houses

By Elizabeth Meredith Dowling; Foreword by Marc Appleton

Published by Rizzoli International Publications, New York, 2013.

240 pp; Hardcover; Over 175 Full-color images; $60;

ISBN 978-0-8478-3385-6

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

For many years I’ve been aware of some superb designs by architect Michael G. Imber, FAIA, (www.michaelgimber.com) through his Palladio Award-winning projects (2010 and 2011) and his appearances in various publications. But I never fully understood the scope and transcendent qualities of his architecture until I picked up the Rizzoli monograph that showcases his firm’s exceptional work. Imber’s treatise rises above the usual monographs that are collections of “beauty shots” with the goal of attracting new clients and massaging the creator’s ego. Such monographs have little to teach the design professional. By contrast, the Imber compendium, besides providing the expected abundance of gorgeous images, also rewards the reader with an understanding of how the architect produces such beautiful buildings.

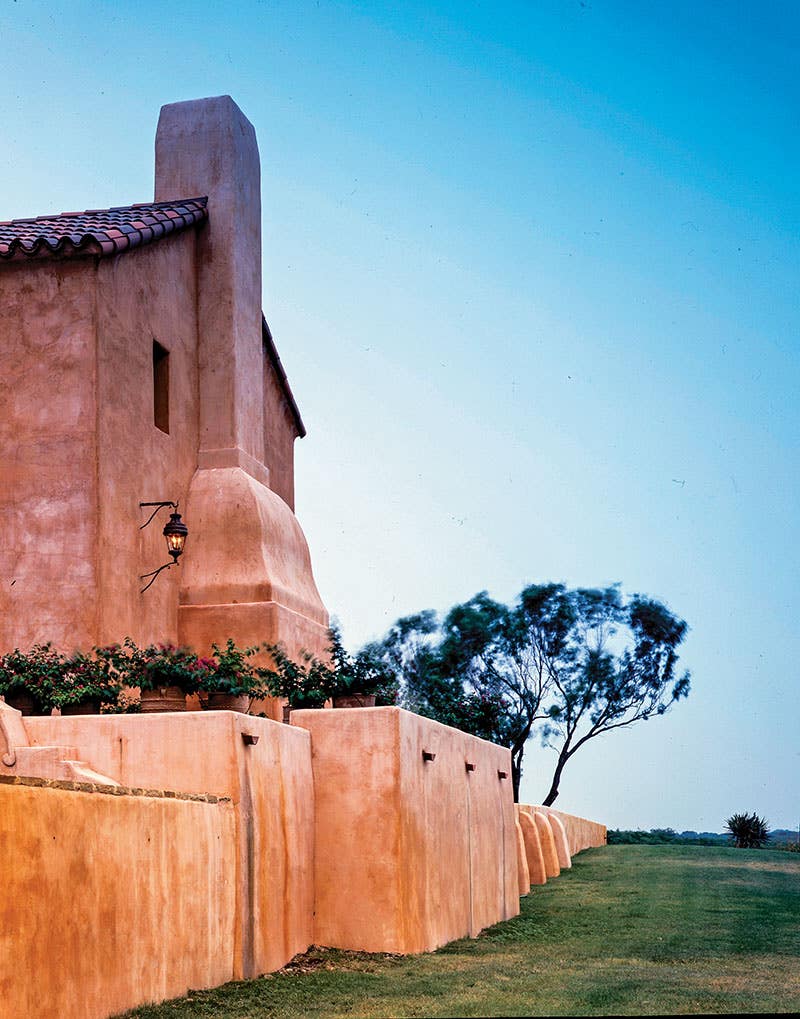

Some might glibly describe Imber as a “regional architect.” And it’s true that most of his creations are rooted in the history and building traditions of the desert Southwest and Mexico, with an especially deep connection to the architectural heritage of his native Texas. But there is no particular “Imber style.” Each project is a carefully worked-out synthesis of the client’s program fused with the special character of the adjacent landscape, regional building traditions, and local materials. As an example of Imber’s design versatility, alongside many of the monograph’s projects that exhibit strong Southwestern influences, we are shown an elegant pair of adjacent Palladian villas he built for brother and sister Italian clients.

Modernists use words like “nostalgic” and “romantic” as derogatory labels to dismiss historically imbued architecture, but Imber welcomes such terms. As he says: “Our homes are meant to be the most comforting physical realization of our lives . . . they should embody both our personal and cultural memories. This cultural memory is at the root of our architectural practice.” Where contemporary starchitects revel in ever-more-complex exercises in geometry, Imber strives to create buildings that embrace their landscape and historical context.

The secret sauce of the firm’s practice is Imber’s emphasis on the art of drawing: pencil sketches, watercolors, and ink wash renderings. “Rendering expresses design,” he declares. Long before he was an architect, Imber was an inveterate sketcher in pencil, pen, and watercolor. He asserts that the elimination of hand drawing from basic architectural education directly correlates with the current profession’s lack of ability to create beautiful buildings.

Imber’s artistic skills come into play at the start of the design process through watercolor studies of the site and surrounding landscape. The physical process of passing salient elements of local character from eye to brain to hand imparts a visceral understanding of the space he’s been assigned—a level of comprehension that’s far deeper than what can be obtained from mere looking. Ink wash renderings, in particular, allow study of composition, light, and form that greatly assist in building massing and details. Imber finds special inspiration in watercolor and rendering from the prior work of architect Bertram Goodhue and the landscape firm of Shepherd and Jellicoe.

Imber’s life-long examination of Southwest building traditions has also made him keenly aware of the role that skilled craftsmen played in evolving the unique look of buildings created in harsh climate. Undulating curves of stucco and adobe surfaces . . . hammered texture of hand-forged ironwork . . . structural timbers made from bark-stripped tree trunks . . . walls of uncut stones . . . colorful hand-painted tiles . . . all these elements show up in Imber architecture. But the details are not handled as pasted-on afterthoughts, but rather as elements integral to the underlying structure.

Images in the monograph include not only stunning photographs of projects ranging from bungalows to sprawling ranches, but also incorporate beautiful reproductions of Imber’s renderings and watercolors that are essential to his design development. As a bonus, plans that show basic building layout accompany most of the projects. These plans are especially helpful in understanding Imber’s larger projects in which their size is camouflaged by clever massing, making it seem like the structures have grown organically over time.

The text, authored by Elizabeth Meredith Dowling, retired professor of architectural history at Georgia Institute of Technology, provides not only lucid descriptions of each project but also adds insights into Imber’s design process. And she includes delightful personal details, such as the watercolor kit Imber uses today was a gift from his artist-aunt who presented it to him while he was still in high school. The foreword by architect Marc Appleton gives us additional personal background that only a long-time friend can provide.

With its graphic proof of design benefits that accrue from the skills of hand drawing and rendering, this book should be required reading in every school of architecture.

Editor Emeritus Clem Labine is the founder of Traditional Building, Period Homes andOld-House Journal magazines. He also launched the Palladio Awards program in 2002.