Features

The Whisky Watercolor Club

Photos courtesy of the architects

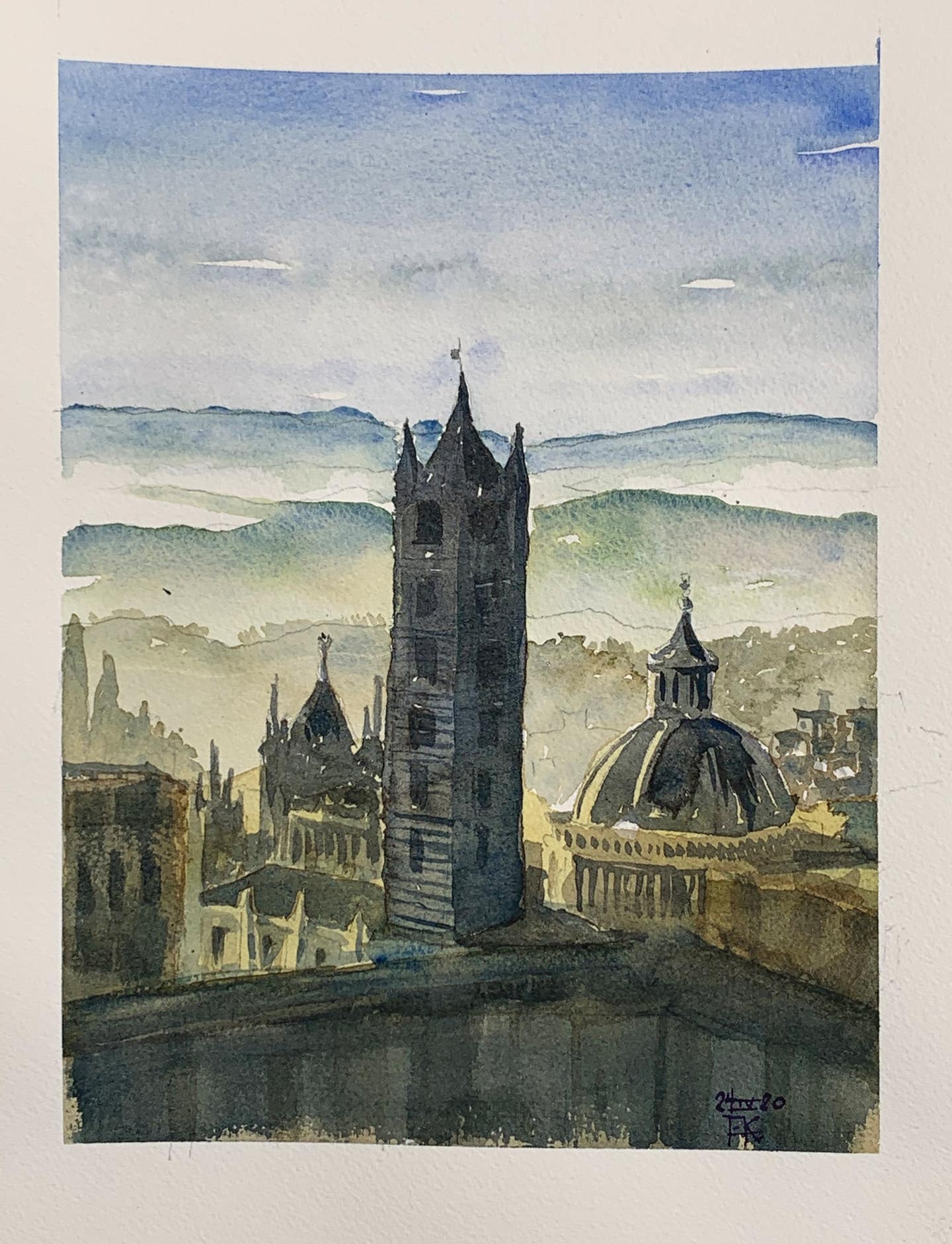

Born during the 2020 pandemic, the Whisky Watercolor Club quickly became a lockdown lifesaver—part artistic endeavor, part conversation-starter, and part camaraderie-builder.

Now it’s an enduring tradition. Every Sunday afternoon at 4:30, five of the nation’s busiest architects—Michael Imber, Tom Kligerman, Doug Wright, Steve Rugo, and Ankie Barnes—gather together on computer screens via Zoom. Each of them pours a glass of his favorite liquor, then pulls out a watercolor kit, and a blank sheet of paper. They all paint the same subject—and talk about technique, respected artists, and each other.

Architecture and office issues sometimes come up, since they all deal with the realities of running a firm during the week. Usually, though, the calls are a mix of banter, friendship, and common purpose. This club is connective tissue between the five—and an art form unto itself.

“It was something to look forward to during Covid, and it continues now,” says Kligerman, partner in New York-based Ike Kligerman Barkley. “We paint and talk and there’s ribbing and constructive criticism—there’s the social aspect.”

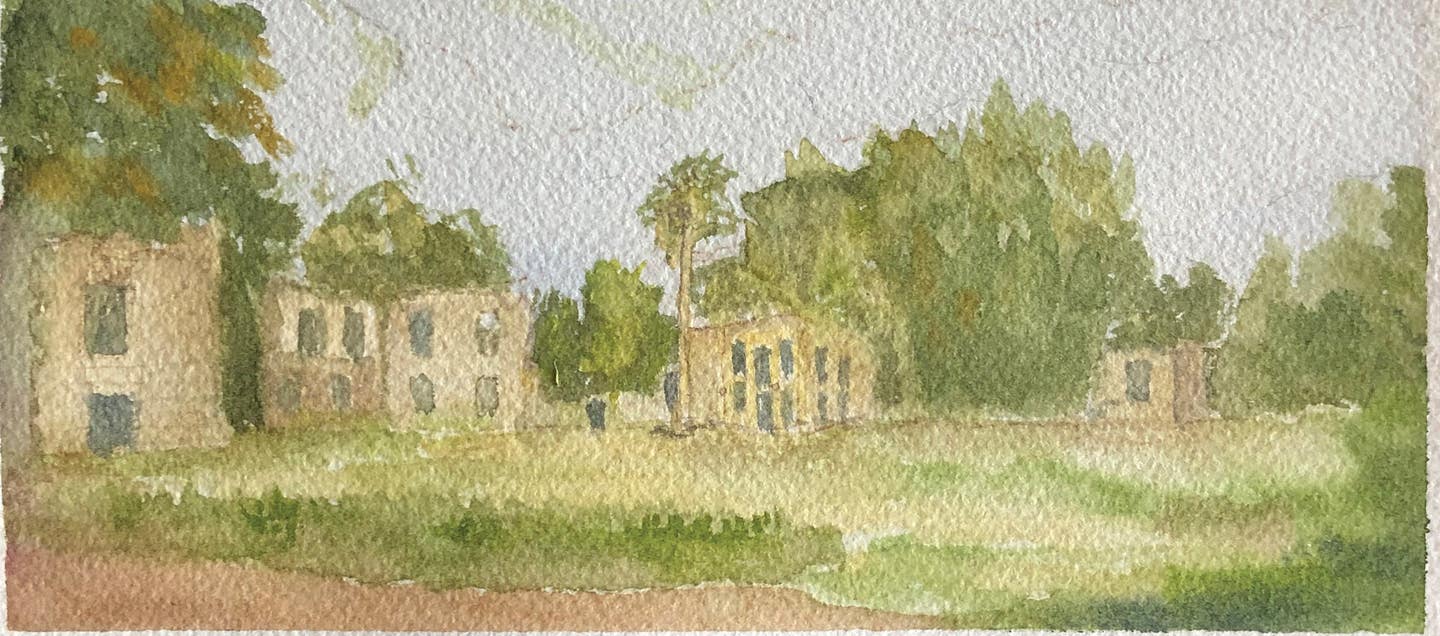

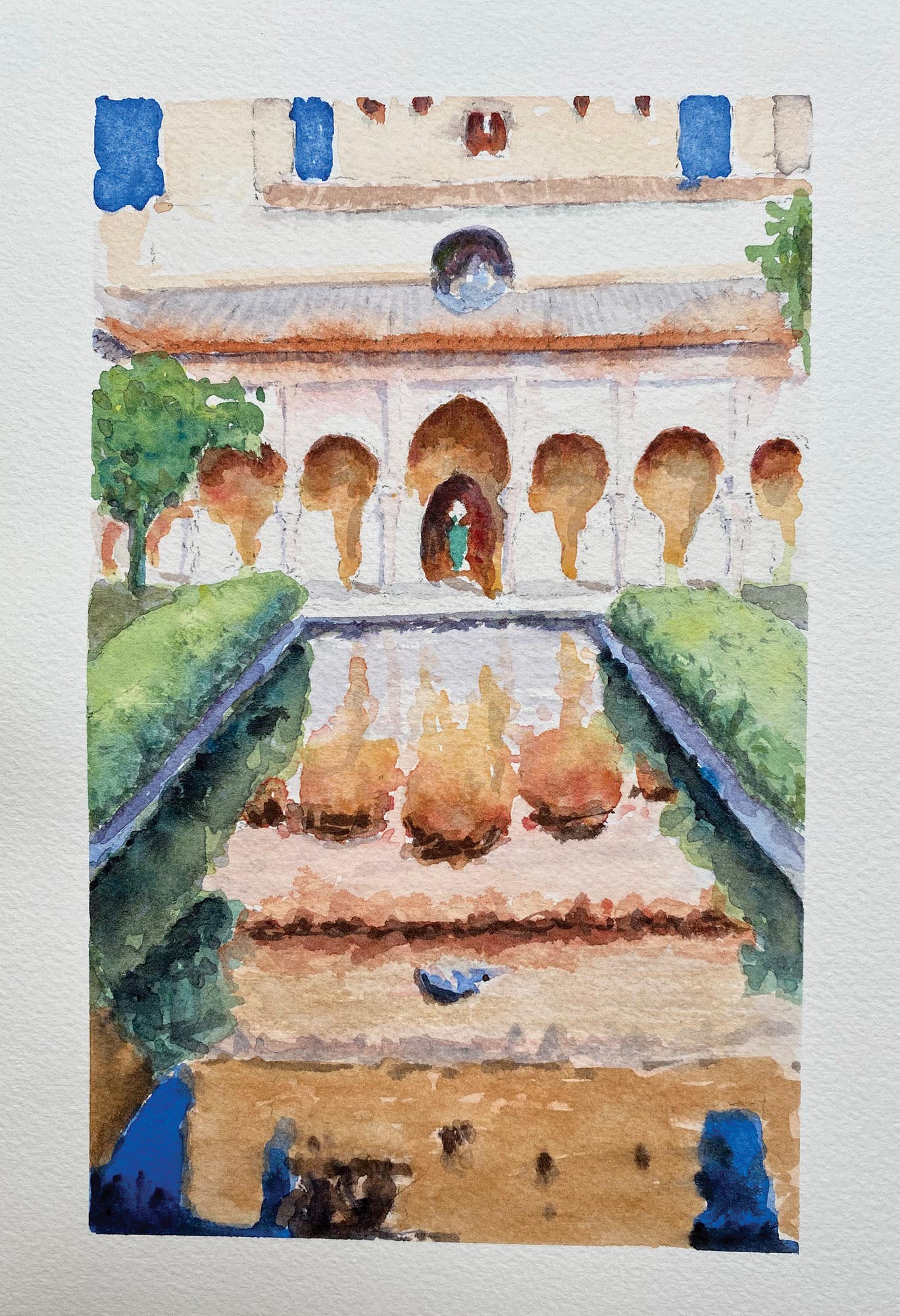

It’s a new riff on an old habit for these five classicists. In years past, they’ve traveled to England, where they once stayed in an Edwin Lutyens house in Surry, drawing and painting over a morning cup of coffee or tea. In February 2020, they embarked on a tour of India sponsored by the John Soane Foundation. And what they found there, they painted with watercolors.

But soon enough, reality barged in on that South Asian expedition. “It got cut short because of the pandemic,” says Kligerman. “We came back to the U.S. and the lockdown.”

They scattered across the country. Offices were closed and salaries slashed. The architects were isolated at home, worried about where the world was going and whether they’d survive. But by early March, they were back in touch. “I said: ‘Let’s get on Zoom on Sunday afternoon—we can have a drink and talk about watercolors,” Kligerman says. “So we painted during the week and talked about it on Sunday.”

Then Barnes’ spouse made an intuitive suggestion. “My wife said that there was no reason not to paint by Zoom,” the principal in Barnes Vanze Architects in Washington, D.C., says. “So over the course of a month, we decided to do it at cocktail time because we were still freaking out about Covid—and we started painting in the evening for six to eight months.”

It was a weekly exercise during a time of uncertainty. “It provided a light moment—we had been kind of moping around,” says Wright, principal in New York’s Douglas C. Wright Architects. “The extra time the pandemic afforded us gave us the time to do it.”

This club’s all about the watercolors—and the people. “We’re deep-diving into an appreciation for art,” says Imber, principal in the San Antonio firm that bears his name. “It’s important to get together and connect—I wouldn’t dare miss it.”

To prep for the weekend sessions, they’ll text one another during the week with potential thoughts and images to work from. “It’s like hitting a wasps’ nest,” Wright says. “I’ll send out a text and get five, six, ten, and then 80 or 100 back—like a young schoolgirl—and on Saturday, we decide.”

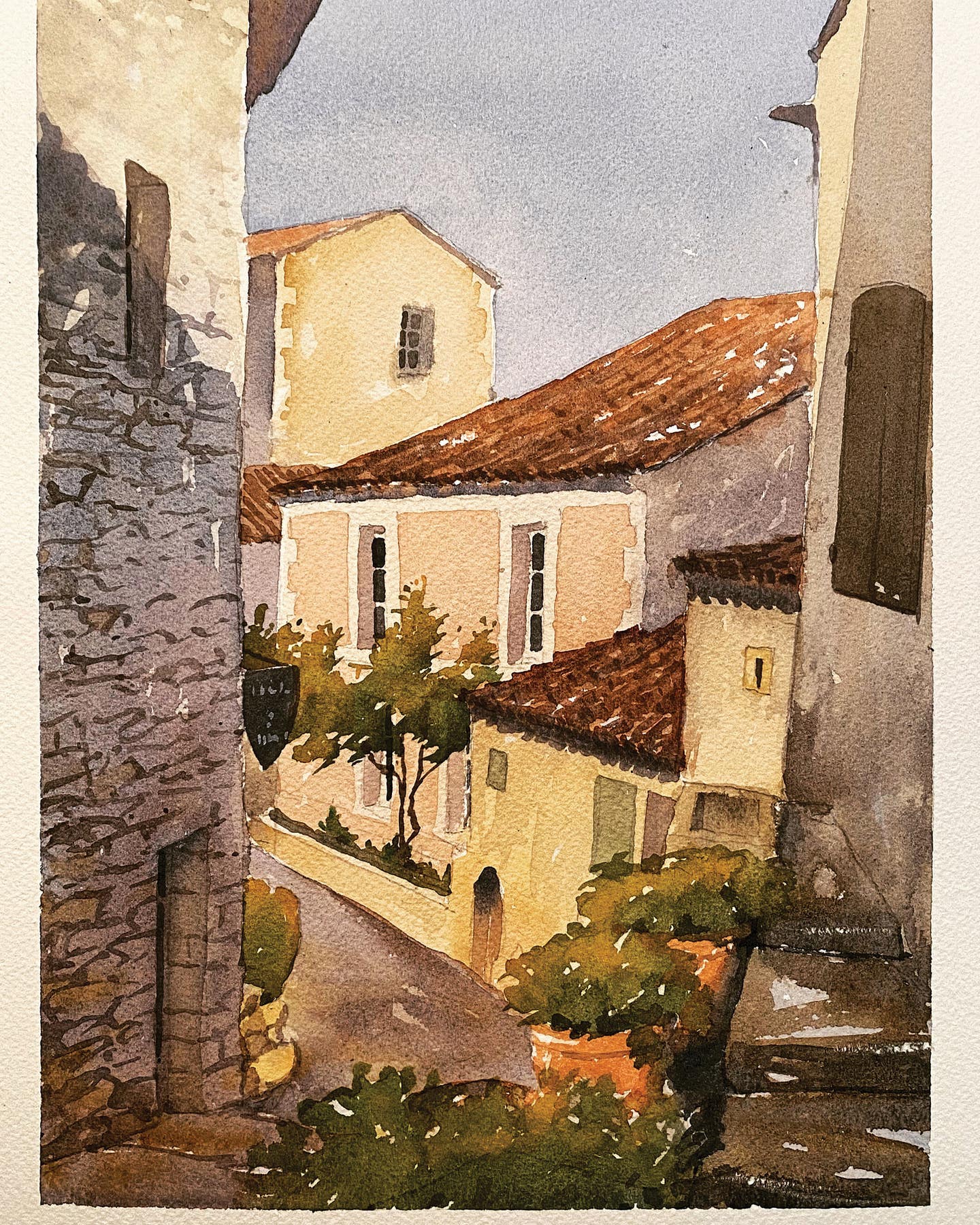

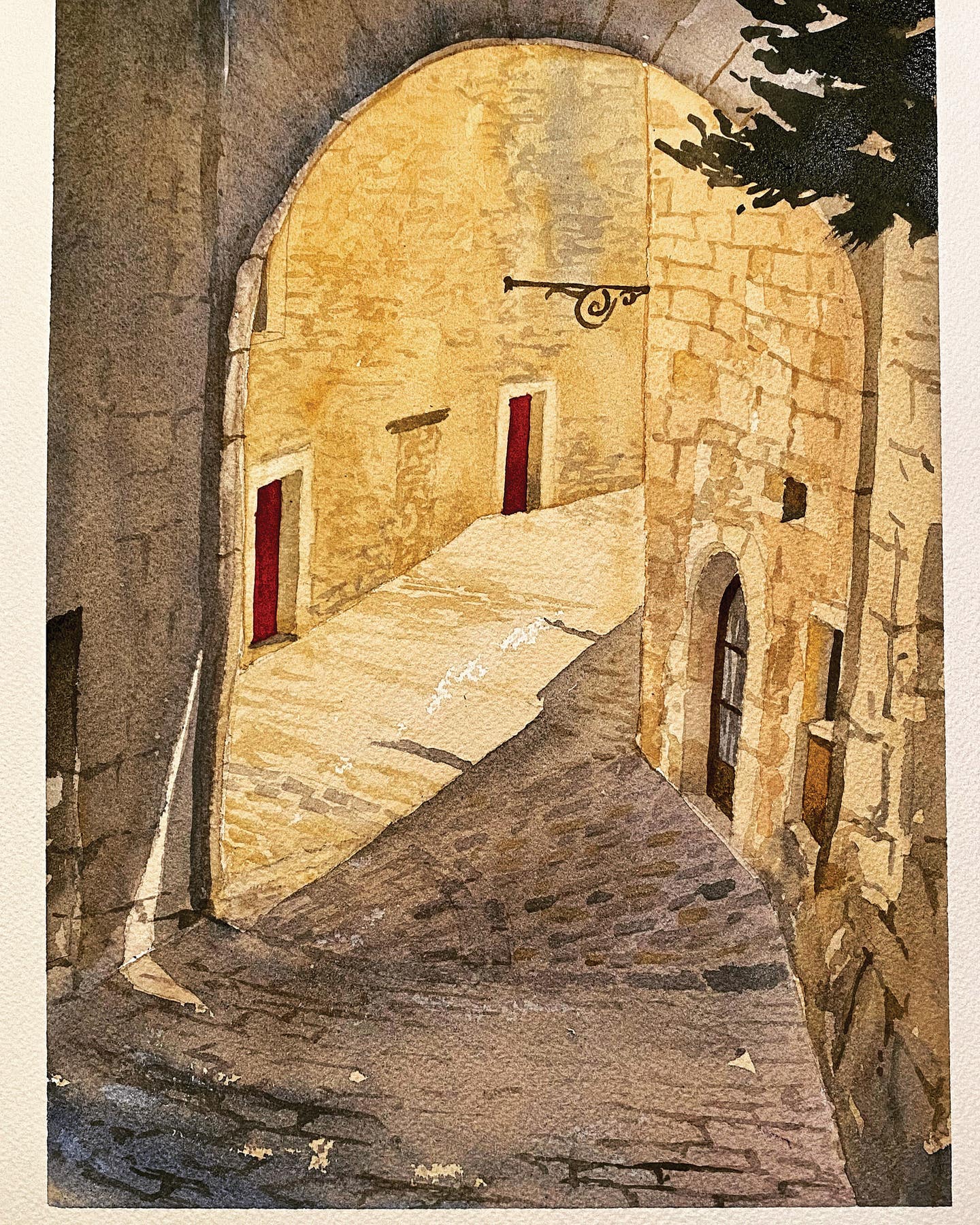

Their subject matter leans toward landscapes, but still-lifes and flowers find their place in the mix too. “We also look at other techniques, like Homer or Sargent, for a new appreciation of how other people do things and how to develop ourselves,” says Rugo, principal in Rugo Raff Architects in Chicago.

And they learn from each other. Imber may be the only one of the five with formal watercolor training, but they all work hard at developing their individual talents and styles. “We think of Michael as a leader and as inspiration because he does such great watercolors,” Wright says. “Everyone has gotten much better, plus there’s a lot of personal development.”

That’s in part because of the discipline of their weekly get-togethers. “What you learn quickly is that the more you do it the better you get,” Imber says. “Some of us started out as novices, and now are doing some real gallery-worthy paintings.”

And they’re motivated. “I want to become a better painter, and do more of it,” Barnes says. “We’re constantly looking for things to be painting—color and light and clouds. It’s a constant challenge.”

Kligerman looks at the exercise as a way to heighten his power of observation—to understand how his subject matter comes together. “There’s the dynamic of color—usually I’m thinking about form-making in architecture, and less about color,” he says. “So now I’m understanding color better—you take in information and see things better.”

Rugo believes that painting has changed the way he perceives his environment. “I see trees now not as trees, but as dark shade, and work to capture that in 30 seconds,” he says. “You see colors you’ve forgotten—and then where does white or black enter into it? You get excited because you see a lot more.”

Painting has been part of Imber’s life since his aunt gave him a watercolor kit when he was in high school. Today it’s part of his architecture—he uses it in his presentations to clients as a way to communicate. And now, every Sunday, he’s learning new lessons. “How do these two colors go together?” he asks. “How does the light work? The shadow, shading, and composition? What can I learn from restraint?”

Imber estimates that since the club started, he’s done more than 200 paintings. Kligerman says he’s easily done 100, laying some out in a recent art show and selling a number of them. “It used to be I’d do maybe one watercolor every six months, and now it’s one every three days,” he says. “There’s a wild range—some get torn up and some are pretty.”

Barnes has painted about 100 also, with similar results. “Some are forgettable and some are unforgettable,” he says. Rugo counts about 75 to 80, while Wright estimates he’s painted a whopping 300. “About 10 percent are ones I really like, or point the direction to something that crystallizes,” he says.

Their choices in whiskies are as varied as their painting styles. Barnes is a fan of single malts and bourbons, accompanied by an oversized ice cube. Rugo’s tastes run the gamut, from Mezcal Negronis to Kentucky artisanal bourbons to Irish Whisky. Imber’s favorite is Glen Fiddich, while Kligerman leans toward Woodford Reserve. As for Wright, he prefers the peaty tones of a Laphroaig single malt.

And he says he’s open to contributions from any reader.