Projects

Whole Again Landscape

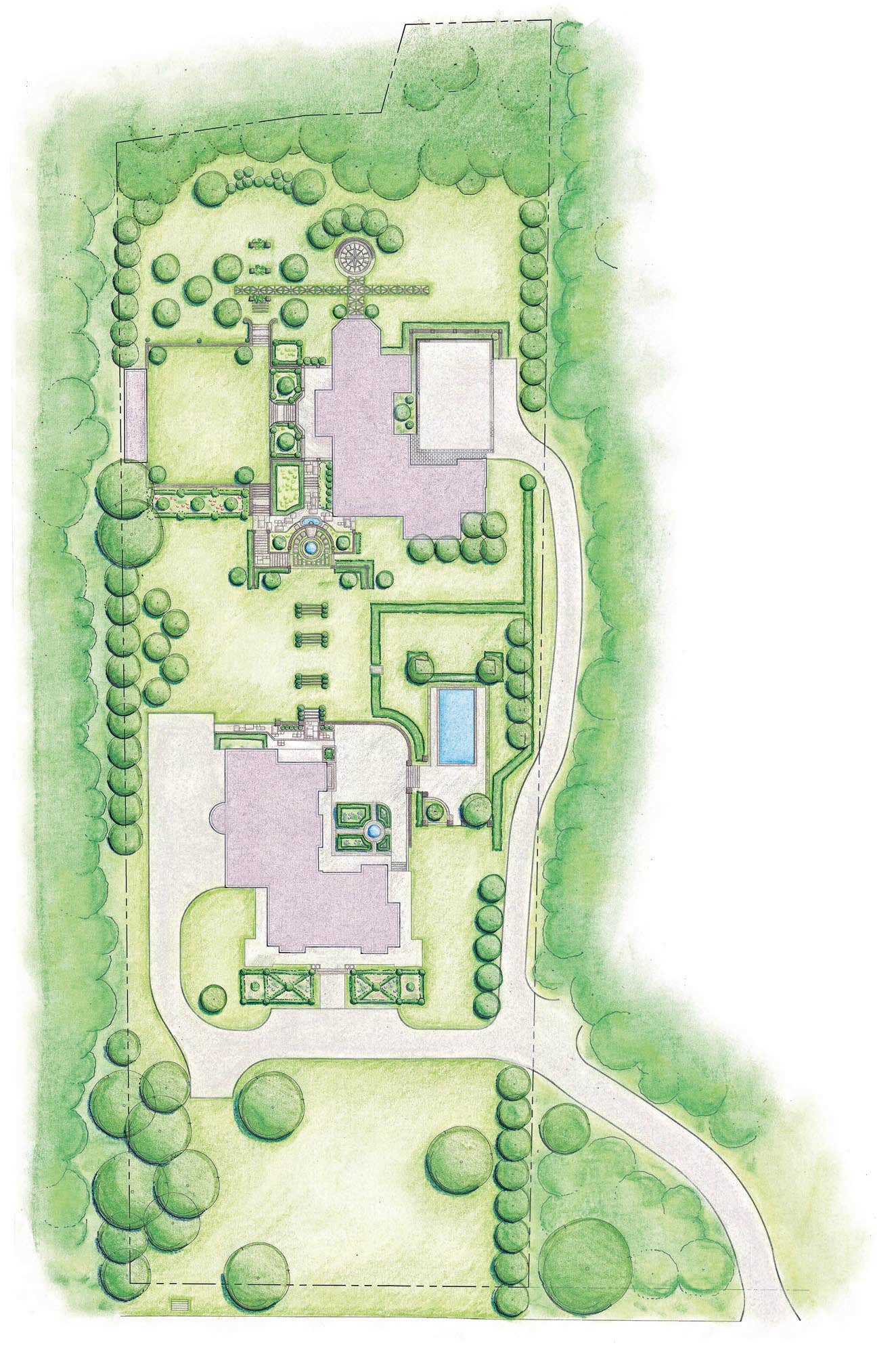

In the early 1920s, Ellen Biddle Shipman devised a garden and landscape for a hillcrest property in Ridgefield, Connecticut. In 2009, landscape architect Janice Parker set about restoring it to its former grandeur.

Substantive yet graceful, the two-story home was originally designed for a wealthy banker. The property has undergone a few permutations, including a stint as a nursing home. Ultimately, the main house burned down, and the property was divided into two lots—two very at-odds lots.

“When I got the project, I went to Judith B. Tankard, who wrote the book on Ellen Biddle Shipman,” says Parker, noting that there weren’t any real records of the property to guide her. Encouraged by Tankard’s words, she went forth with her own ideas, looking to the book and articles for inspiration.

Her canvas was dotted with incongruities. The client’s house sat high on a ridge, while a second house was posited at the base of a dramatically steep slope that characterizes the rear grounds. The first order of business was to address the uncomfortable relationship of the lower house to a round, Shipman-designed historical fountain. (Parker describes the house as having been “jammed into the fountain.”) For years, the client had looked down on the problematic situation at the edge of her property, and she was anxious to resolve it.a round, Shipman-designed historical fountain. (Parker describes the house as having been “jammed into the fountain.”) For years, the client had looked down on the problematic situation at the edge of her property, and she was anxious to resolve it.posited at the base of a dramatically steep slope that characterizes the rear grounds. The first order of business was to address the uncomfortable relationship of the lower house to a round, Shipman-designed historical fountain. (Parker describes the house as having been “jammed into the fountain.”) For years, the client had looked down on the problematic situation at the edge of her property, and she was anxious to resolve it.

Upon purchasing the lower portion of the original property, consideration was given to moving the fountain. However, restoration experts advised against it. The Dumbarton and Oaks-like pebbled concrete finish was crumbling and would likely be destroyed altogether in the move.

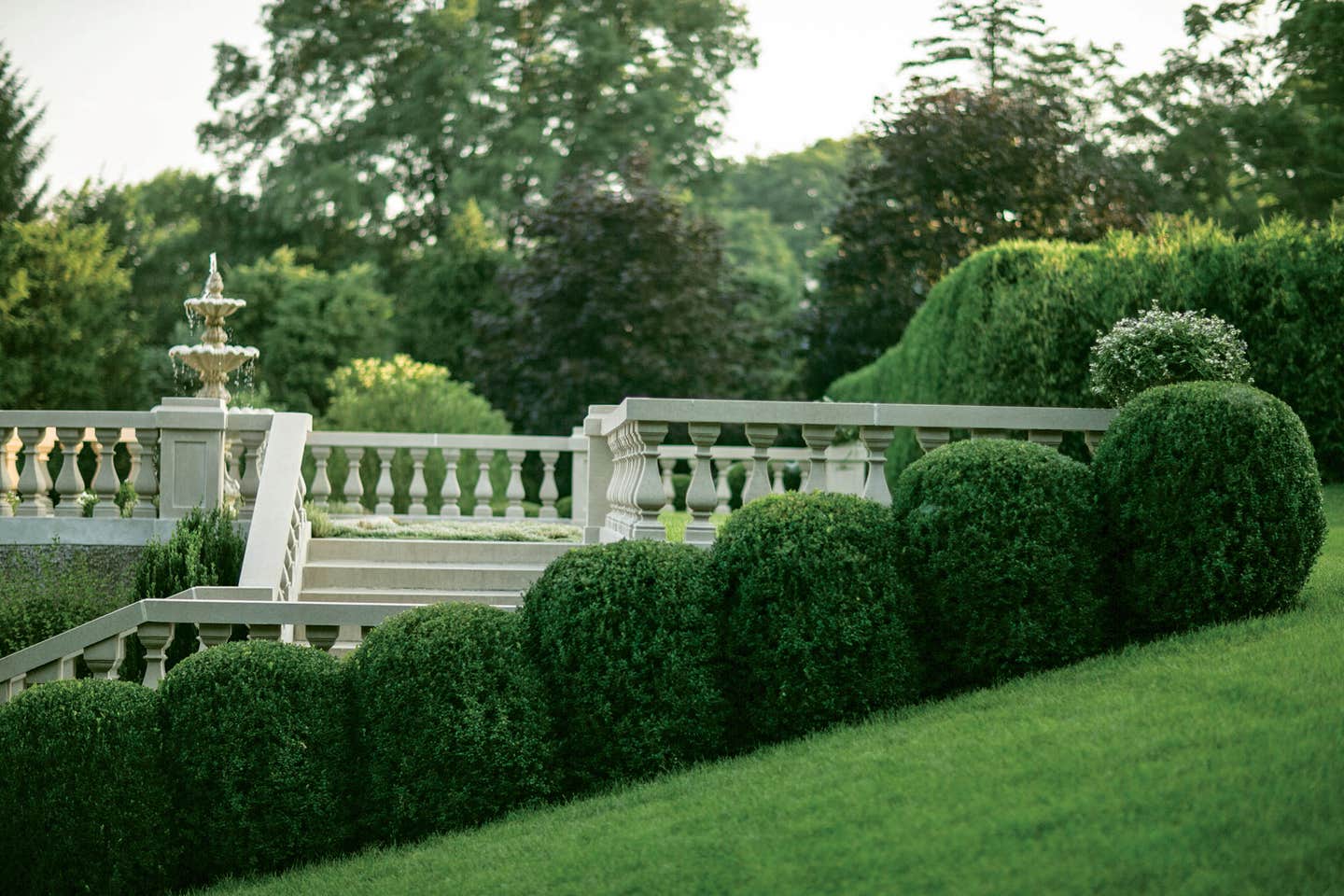

The solution was to “soften things” around the fountain and turn it into a centerpiece. There weren’t any stairs coming down around the fountain, so Parker worked with architect Sean O’Kane to come up with a design that worked. Additionally, all of the balustrades were gone, but they were able to use a few pieces that had been left onsite to replicate them.

They restored a retaining wall that had completely collapsed along one side of the large square lawn, and Shipman’s pool pavilion was given new luster—it’s not functional but its aesthetic value is unparalleled. Parker also added a custom bench by New England Ornaments. She notes how the space works now: “The level lawn panel feels very nice and calming. Without it everything keeps dropping off. It is a wonderful place for weddings, family event and the many fundraisers the client hosts.”

Though the division of the property into rooms and corridors helps to make sense of its circulation, Parker says it was a challenge to find the geometry in this project. Because the houses were never meant to be together—they were both built in the early 2000s—and the fountain was in such an odd location, she was dealing with pieces from different puzzles and their edges didn’t line up. “We had to play around quite a bit,” she recalls. “I felt symmetry was really important because otherwise you didn’t know where to go.” To that end, she put in a British flag-patterned pathway on the lower level; and laid a pebble mosaic compass rose, trimmed in tumbled bluestone brick and dressed with a necklace of hornbeams. She also kept the stairs on one line to tie the houses together.

The lack of large trees added to the disparate picture. “It seemed to me, laying out all of the structures and elements was of course important, but holding the volume of space together with trees and accents of plants was more important because there were not any old trees left between the two houses.” The repetition of fastigiate copper beeches against the pale stonework serves that purpose.

The historical character of the fountain, pavilion, other other structures called for a program that would lend “age” to the planted landscape, too. Traditional greenscapes of hornbeams, magnolias, dogwood, and boxwood parterres are in keeping with the Classical tradition, while the use of chartreuse Hakonechloa grass, ‘Limelight’ hydrangeas geas, Deutzia gracilis ‘Chardonnay Pearls’, weeping Japanese maple, and ‘Roseanne’ geranium are contemporary choices. Parker explains that the client didn’t want a lot of color, so she relied on bronzy purple accents to set off the primary green spaces. They also serve as a bridge between the whites and pinks of the arching rose blooms.

The experience of the grounds is one of wonderment, which was part of the design intent. “What I always feel, and hope other people feel—especially in the early spring, when the fastigiate beeches are ruby red in the light—is like Alice in Wonderland,” says Parker, noting the many surprises visitors discover as they tour the property. “Rubies on trees,” dolphin fountains, a statue of Aphrodite, a wild stag sculpture, and even the pool pavilion are “playful focal points,” which combine with Classical elements to evoke romance.

For Parker, the property’s restored glory is a tribute not only to Ellen Biddle Shipman but also to pioneers like Beatrix Farrand and Annette Flanders. “There were a lot of important gardens designed in the last century that really set the tone,” she says, recognizing the potential her predecessors bestowed on the suburban garden—the potential to create timelessness by combining a limited plant palette with traditional elements and playing with proportion and space. “Simple plantings of very pretty, special plants can be used in a way that is not predictable,” notes Parker, who sees this particular landscape as Classical, though located on a suburban lot. “By keeping the Classical pieces, it doesn’t come off as pretentious because it is historical, but it avoids the suburban predictability.”

Parker ultimately ties successful suburban garden design to the matching success of the women who mapped a course for future female landscape architects. To convey her respect, she shares this quote:

“Not for one instant will this daunt a woman to whom landscape design is a master passion. She exults in the demands upon every power of mind and body. In other words, she is an artist and, insofar as her art is concerned, a willful fanatic.”— Mary Bronson Hartt, Women in the Art of Landscape Gardening, 1908

This sensitively reimagined landscape is evidence that Janice Parker is one such undaunted artist.